Oakville at War

Women in War

Panels

IntroductionFirst World WarSecond World WarFurther ResearchVeterans Interviews (click on Details to play video)“Women, this is your war too!” recruiting posters proclaimed in 1942. Oakville resident Rose Cutmore agreed. She joined the Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service in late 1942, one of the first generation of Canadian women allowed to enlist in the forces. Bill and Allen, Rose’s two brothers, and her future husband, George Daikens, were expected to serve their country. But the Canadian government, not comfortable with the “weaker sex” participating in the armed forces, did not create service roles for women until almost two years after the start of the war.

Women’s first opportunity to volunteer for the services came in July 1941. At that time Canada created the RCAF women’s auxiliary air force, an embarrassed response to Britain’s offer to send its own Women's Auxiliary Air Force to Canada to work at air training schools. Soon after, the defeats suffered in the first years of the war and the subsequent need for more men overseas dispelled any further doubts about the role of women in the armed forces. Both the army and navy realized that women could ably take noncombat roles and free men for fighting. The creation of the Canadian Women’s Army Corps (CWAC) in August of 1941 was followed in July 1942 by the formation of the Women's Royal Canadian Naval Service.

But despite the enthusiasm and competence of women like Rose Cutmore, Canadian society was not yet ready to see women as anything other than traditionally feminine. Women who joined up were sometimes regarded as immoral, and some women were actively discouraged by parents, husbands, and boyfriends from enlisting.

At the end of 1942, the Oakville Record Star printed an article that seems determined to assure women and their families that a girl could retain her virtue and femininity, even in uniform. “Women in uniform are completely themselves, with their feminine personality and a feminine competence for the job …” the Oakville Record Star reported in an article titled “Women in uniform discover that in the army daintiness is a ‘must.’” The article continued, “Putting on a uniform doesn’t change a woman … she’s still the woman who does the cooking, the nursing, the typing, the general office work…”

By the end of the war the women who did the cooking, nursing, typing, and general office work, as well as those responsible for such tasks as driving, operating X-ray machines, and repairing radios had proven the Second World War was their war too.

Women’s first opportunity to volunteer for the services came in July 1941. At that time Canada created the RCAF women’s auxiliary air force, an embarrassed response to Britain’s offer to send its own Women's Auxiliary Air Force to Canada to work at air training schools. Soon after, the defeats suffered in the first years of the war and the subsequent need for more men overseas dispelled any further doubts about the role of women in the armed forces. Both the army and navy realized that women could ably take noncombat roles and free men for fighting. The creation of the Canadian Women’s Army Corps (CWAC) in August of 1941 was followed in July 1942 by the formation of the Women's Royal Canadian Naval Service.

But despite the enthusiasm and competence of women like Rose Cutmore, Canadian society was not yet ready to see women as anything other than traditionally feminine. Women who joined up were sometimes regarded as immoral, and some women were actively discouraged by parents, husbands, and boyfriends from enlisting.

At the end of 1942, the Oakville Record Star printed an article that seems determined to assure women and their families that a girl could retain her virtue and femininity, even in uniform. “Women in uniform are completely themselves, with their feminine personality and a feminine competence for the job …” the Oakville Record Star reported in an article titled “Women in uniform discover that in the army daintiness is a ‘must.’” The article continued, “Putting on a uniform doesn’t change a woman … she’s still the woman who does the cooking, the nursing, the typing, the general office work…”

By the end of the war the women who did the cooking, nursing, typing, and general office work, as well as those responsible for such tasks as driving, operating X-ray machines, and repairing radios had proven the Second World War was their war too.

Rose Cutmore enlisted with the Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service in 1942. After basic training she was posted to H.M.C.S. King’s in Halifax. Married in February 1944 to George “Bud” Daikens, she left as a Leading WREN and expectant mother in 1944. Details

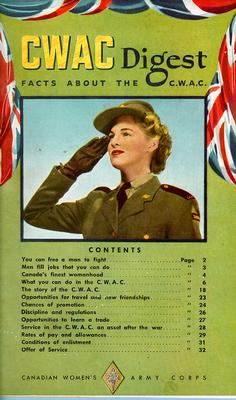

Used to recruit volunteers, this CWAC booklet contained a long list of occupations women could perform in order to “free a man to fight.” It contains a quote from Madame Chinag, "No cause, no country can be great unless its women work for it." Details

Canadian Women's Army Corps marching in a Victory Loan Parade, 2 May 1943, Montreal. Details