Pro History Project: History by Design

II. Communities

Panels

Pro History ProjectOral HistoriesFrom The Heartland: Ninteenth Century Buildings of Victoria CountyAcknowledgementsIntroductionThe Heartland in PerspectiveI. Rural Life, Industries and TransportationII. CommunitiesIII. EstatesIV. Gathering PlacesConclusionBibliographyMissing Slides and PhotographsLinks

Pro History Colour SlidesOral HistoriesPro History Black & WhiteIn contrast to the countryside, communities more directly mirrored changing European, British and American architectural fashions. From the county seat at Lindsay to the smallest hamlet, community (i.e. urban) architecture reflected a very different social world preoccupied with commercial and transportation functions. These communities also served as a focus for cultural, religious and governmental building. But in this section we are principally concerned to examine the closer imitations of architectural styles demonstrated in individual family homes and in commercial architecture; two areas that most effectively illuminate men’s materialist aspirations.

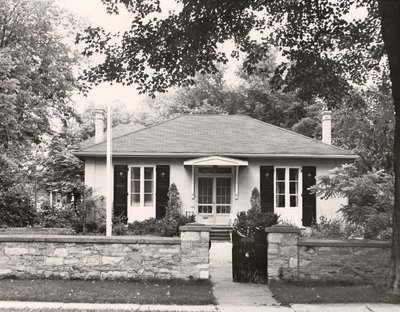

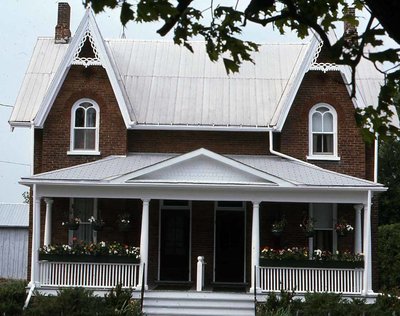

Wallis House, Oak Street, Fenelon Falls Details

A closer imitation of metropolitan architectural styles is readily seen in some of our earliest examples such as in John Langton’s ‘Blythe House’, the Wallis house in Fenelon Falls and Lindsay’s town surveyor S. Deane’s ‘Ontario Cottage’ on Bond Street. These houses were built by British immigrants with strong cultural ties to their homeland. This attachment is revealed in local variations of certain cottage designs popular with propertied immigrants in the early nineteenth century.

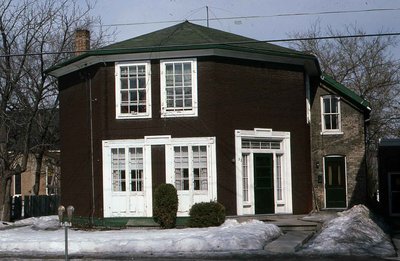

Plate 45, Ontario Cottage, Bond Street, Lindsay, private dwelling Details

The best example of this elegant cottage style is Lindsay’s Ontario Cottage built in the 1850s in Plate 45. This house exhibits the traditional French doors, low hip vault roof and, therefore, one storey appearance though actually one and a half. This cottage design originated in the hotter climes of the British Empire. While enjoying a great popularity among the propertied gentry throughout the empire, it soon disappeared from Canada due to the poor insulation of the low hip vault roof. The upper storey was either extremely hot or extremely cold, depending on the season, and suffered as well from a lack of ventilation. Originally these houses were designed to incorporate porches that ran around all of the walls though in this case it has long since been removed. The porch not only afforded protection to the house but, as Anne Langton remarked, it provided a place of exercise for women to walk about and take the air without being exposed to the perils of Upper Canada’s famous mud.

One of the more curious ‘styles’ of nineteenth century architecture was the mid-century fashion of building octagonal houses. This fashion was begun by an American phrenologist, O.S. Fowler, who wrote a book on the advantages of grout wall construction (i.e. poured lime mortar) and the greater interior space available to a circular building. This is true in that the circle contains the greatest amount of space within the shortest perimeter. Fowler’s book, if not his experiments in actually building houses, was a great success. John Remple, author of Building in Wood, has documented over two score of such buildings in Ontario. These are concentrated in the Niagara Peninsula and along the north shore of Lake Ontario; areas most in contact with the United States.

Plate 46, Peel Street, Lindsay, octagonal house Details

There are, however, a few examples scattered throughout the province and fortunately there is one in Lindsay. Lindsay’s octagonal house (Plate 46), on Wellington Street, was built in the 1850s apparently by T.J. Brooke, Victoria’s first professional architect, probably in the period 1854 – 56 when the present building lot was separated from a much larger area. The house was subsequently bought by Thomas Keenan, a famous Lindsay merchant whose pre-1860 commercial block is still standing on Kent St. W., in 1857. This house was originally of frame construction with a ground level octagonal porch and an octagonal belvedere. Both of these have disappeared as well as the frame exterior under a skin of insulbrick. This house and the Ontario cottage were built during Lindsay’s first building boom in the 1850s due to the construction of the Port Hope-Lindsay Railway in 1856-57.

These two interesting examples of early building, however, are atypical of the area’s overwhelmingly solid Victorian building. This, of course, is to be expected since those surviving stone, brick, and a few of the once numerous frame, houses were only built in the 1850s and 1860s. Victoria County was, for Ontario, a lately settled region where even in the 1850s log and frame buildings outnumbered the more permanent brick by a ratio of ten to one. Because of this relatively late period of permanent building construction, we are only concerned here in tracing out the styles that evolved from early Victorian to pre-World War One and a number of vernacular variations in builders’ architecture. For other areas of the province that experienced earlier growth, there were homes built in the English Georgian style. But in Victoria we begin with Early Victorian.

The first early Victorian houses in Victoria were Italianate, a transitional style from early to high Victorian. As A. Gowan has pointed out, early Victorian architecture usually restricted itself to reproducing the details of one fashionable style at a time. Italianate was the first of these early styles that allowed a mixing of fashions since it had no fixed criteria, as neo-classic did, that would subject it to purist academic criticism.

The first early Victorian houses in Victoria were Italianate, a transitional style from early to high Victorian. As A. Gowan has pointed out, early Victorian architecture usually restricted itself to reproducing the details of one fashionable style at a time. Italianate was the first of these early styles that allowed a mixing of fashions since it had no fixed criteria, as neo-classic did, that would subject it to purist academic criticism.

Plate 124, St. Mary's Church Rectory, Lindsay Details

Our first stylistic example of Italianate is the Roman Catholic rectory in Lindsay. This is another of the small number of pre 1860 houses in Lindsay (see Plate 124). It was built sometime in the 1850s by J. Knowlson, a real estate speculator.

Plate 125, Entranceway with sidelights, St. Mary's Church Rectory, Lindsay Details

This house, as well as demonstrating such mixed details as gothic transom and sidelight (see Plate 125), exhibits an interesting feature of English villa building.

Interior door with transom and sidelights, St. Mary's Church Rectory, Lindsay Details

West wing, St. Mary's Church Rectory, Lindsay Details

This is the flanking servant quarters, stable and kitchen which work to create a broad symmetrical effect of rational order difficult to encompass in one photograph.

East wing, St. Mary's Church Rectory, Lindsay Details

Beall house, Albert Street South, Lindsay Details

The second example is the now demolished Beall House (Plate 47), built by Thomas Beall, a Yorkshire jeweller via New York state in 1863. The bricks were imported from the United States. This house shows how Italianate could serve as a vehicle for mixing gothic details; note the projecting bay, deep eaves, brackets, and the terraces. The landscape was an integral component in creating that ‘irregular’ romantic picturesqueness and here done so by carefully randomly spaced flower beds and imported trees.

Plate 49, Russell Street East, Lindsay, private dwelling Details

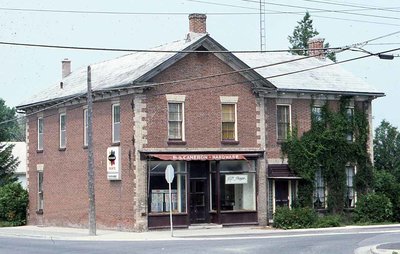

Interesting variants of Italianate that are really more Canadian in inspiration are such houses as the Bank of Upper Canada (Plate 49), built in the 1850s,

Plate 50, Bond Street, Lindsay, private dwelling Details

the county’s first Sheriff’s house (Plate 50) , built in 1865,

Plate 51, King Street East, Omemee, private dwelling Details

and an impressive square brick in Omemee (Plate 51). All three depend just as much on the patterned brick and central projections for visual effect as upon the deep eaves and heavy wooden bracketing. One notes as well the wrought iron decorations over the windows in the Bank of Upper Canada, the Palladian window in Sheriff McDonnell’s house and the louvered shamrock and ‘suicide door’ of the Omemee house where once a large porch had covered the front.

Plate 52, King Street, Woodville Details

One other kind of Italianate was the Tuscan villa mode. The closest example we have is a Canadian L shaped buff brick house in Woodville (Plate 52) with a pyramidal Tuscan tower in place of a porch. There is another example of this in Little Britain.

Plate 53, Oak Street, Fenelon Falls, private dwelling Details

A far more visually appealing house, that reveals how late the Tuscan tower’s appeal ran, is the Graham house in Fenelon Falls built in 1896. Here the tower reflects its later date in being asymmetrical (Plate 53).

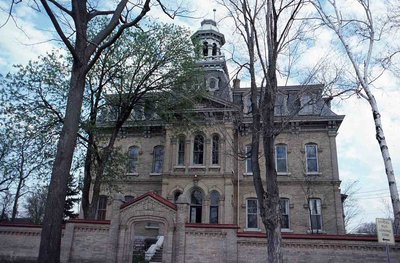

Plate 127, St. Joseph's Convent, Lindsay Details

One important design that did fall outside the English Victorian milieu was the French Second Empire style. This style of building with its full storey Mansard roof, i.e. bell cast, entered Victoria around 1870 and remained to influence the rebuilt Loretto Convent (Plate 127) in 1885 in Lindsay and a number of commercial blocks built in Omemee after the great fire of 1861.

Plate 54, Bond Street, Lindsay, private dwelling Details

The house in Plate 54 is located on Bond St. in Lindsay. It is a particularly fine example of this style with elaborate interior plasterwork and marble fireplaces. The exterior porch treillage is a fret saw cut design while the house itself has an unusual pattern of bricks laid in an undulating course between the second storey and the mansard with factory turned brackets under eaves and wooden dormer decorations.

Plate 19, Brick house, Bolsover Details

A reduced second empire example is the house from Bolsover in Plate 19. Here the mansard roof is the full second storey itself. It was often the case for less affluent builders to imitate this style in a two storey building with the inevitable result of giving the house a smaller appearance than it actually had.

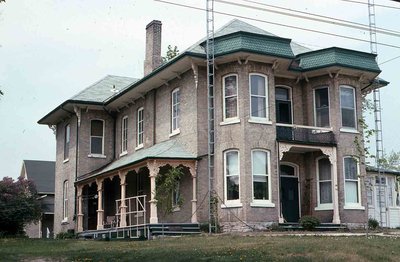

Plate 55, Sylvester house, Lindsay Details

From Italianate’s easy mixing of details it was but a short step to an eclecticism of styles that mixed features and designs from a number of periods in a heady combination of rich and exuberant effects. One of the most forceful of these is Sylvester house in Lindsay (plate 55), once the abode of the leading local manufacturer of farm implements. This is an excellent example of High Victorian with its tower rocketing off upwards supported by zigzag patterns of brick and scale roof tiles in contrasting patterns. Age has mellowed the abrupt contrasts in colour but early photographs show clearly the stark forceful patterns that accent the house’s abnormal vertical thrust.

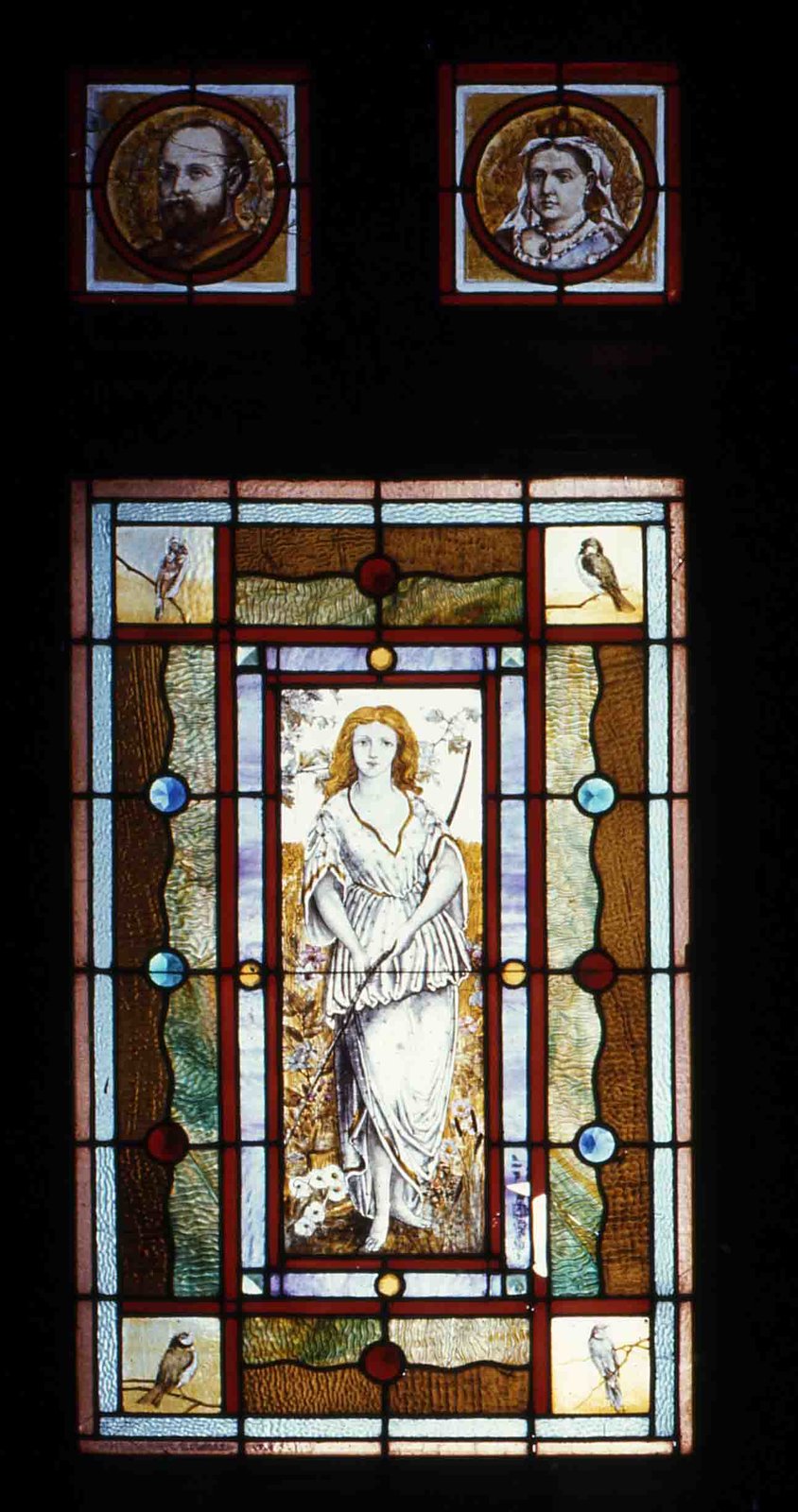

Plate 56, Stained glass door, Sylvester house, Lindsay Details

Of particular note are the interior decorations which effectively mirror the exterior’s vitality; note in Plate 56 the rich detail of the stained glass door with Queen Victoria and Prince Albert in the top corners.

Painted birds inset on door, Sylvester house, Lindsay Details

The house also has rich plaster work, interior brackets and, on each hardwood door, painted bird insets. In true High Victorian fashion the house is a testament to the buoyant optimism of the owner.

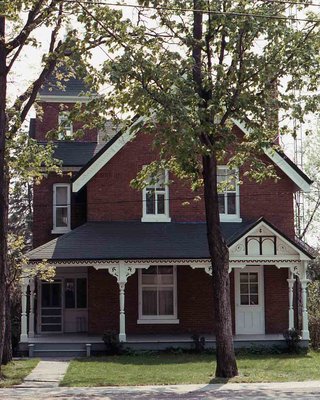

Plate 57, Bond Street, Lindsay, private dwelling Details

This High Victorian mixing of styles can also be seen in Plate 57 and Plate 60. Plate 57 is a high Victorian mixture of Italianate and Second Empire features embellishing a large square Canadian brick house. There are a number of houses very like this one in Lindsay to be found in Fenelon Falls on the main street. Note the reappearance of the hip vault roof with the area’s growing prosperity.

Colborne Street, Fenelon Falls, private dwelling Details

Plate 58, Janetville, private dwelling Details

Plate 58, from Janetville in Manvers Township, is a much more elaborate fusion of French, Italianate and Swiss features with Canadian factory turned woodwork. This house was built by Dr. R. Allen, and it has been appropriately described as Janetville’s own ‘Casa Loma’. As Mrs. Carr has pointed out in her book on the history of Manvers Township, this house has rosewood woodwork, the winding staircase, many fireplaces, the library which still boasts many valuable volumes, elaborate hot water heating systems and bathrooms. Another unique feature is the system of speaking tubes which joined the bedrooms to the kitchen. The third floor was for servants’ quarters. Some of the materials such as the magnificent cut stone for the foundation were imported from Scotland. Pg. 116-117

Plate 61, William Street North, Lindsay, private dwelling Details

By the end of the century one can note a more restrained eclecticism. Carew House (Plate 61) with its semi-circular windows, asymmetrical tower and pagoda dormer is still a model of restraint in comparison to Sylvester House. The interior reflects this toning down through less garish decoration. Instead of brackets there are factory turned bobbins to act as dividers and to embellish the hallway and stairs. Even the Carriage house displays this restraint.

Plate 64, Colborne Street East, Lindsay, private dwelling Details

By the end of the century, building tastes were favouring rather narrow two storey houses which gave an impression of largeness while accommodating a reduced street frontage as town property increased in value. As well high Victorian houses were brought in accord with the new restraint of late Victorian building through visually quiet porches in an effort to ‘modernize’ the wild exuberance of High Victorian. Still occasional flashes of individuality would come through as in Captain Crandall’s house (Plate 64) with its belvedere for the Captain to watch the shipping on the Scugog. Yet even in this house there is a lack of architectural ornamentation. Such decorations as bargeboard and treillage had virtually faded from the scene. Only in the narrow peak of the gable would there be found a vestige of former fancies of wood turnery. Late Victorian building, then, even among those who could afford large houses, had abandoned the powerful effects wrought by High Victorian eclecticism; such ‘irregular’ effects had lost their power to stimulate.

Among the villages there was a far plainer style of building that concentrated more on an expression of materials than of any ‘town’ style. In most cases the villages were intimately tied up with the countryside’s economic concerns and this is reflected in the predominance of brick buildings in such agricultural villages as Oakwood, Little Britain and Woodville and in the predominance of frame houses in such lumbering villages as Bobcaygeon, Fenelon Falls and Coboconk.

Plate 67, Front Street West, Bobcaygeon, private dwelling Details

The majority of frame houses that survived down to the present without major alterations, however, are found in the lumbering villages as in Plate 67 on Front St. W. in Bobcaygeon and

Plate 68, Waterfront Street, Coboconk, private dwelling

Details

Plate 68 in Coboconk. While the predominance of frame points to a relatively less prosperous economy, both of these two houses demonstrate the rich decorative effects even sawn lumber could achieve.

Plate 69, King Street West, Woodville, private dwelling Details

For the agricultural villages, brick was the ne plus ultra of building mediums. The layouts of these houses were simple in the extreme. They were either L shaped or square two storey buildings. (see Plates 69 and 72).

Plate 72, Square Brick House, Oakwood Details

Plate 70, King Street West, Woodville, private dwelling Details

But the richness of effect that could be created with brick patterned around windows and on walls was amazing. One only has to go to Woodville and see an incredible variety of patterns to appreciate what the local carpenter and bricklayer could achieve; see Plate 69, an L shaped house with casement doors opening onto a small iron wrought balcony above a projecting bay under elaborate bargeboard and set against a patterned brick (see also Plate 70).

Plate 71, King Street West, Woodville, private dwelling Details

One of the few houses in Woodville with pretensions to ‘town’ style was Morrison’s buff brick. Not surprisingly this sole exception belongs to the first federal member of Parliament for Victoria West in 1867 (Plate 71).

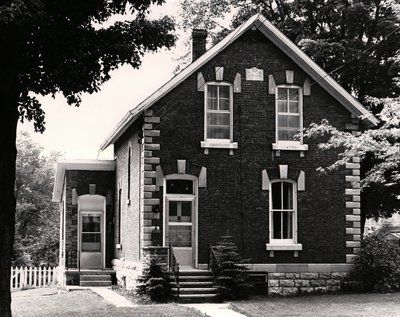

Plate 74, Unusual Brickwork, Little Britain Details

Other vernacular variants of town houses built with bricks can be seen in Plate 74. Here in Little Britain the bricks have been set on their edge instead of lying flat. This peculiar pattern probably covers a framed over house later ornamented with this imaginative method of laying bricks.

Crego Street, Kinmount, private dwelling Details

In Kinmount there is a very unusual colour patterned brick house where every yellow brick is followed by a red brick and vice versa. An incredibly ‘busy’ effect is produced.

George Street East, Lindsay, private dwelling Details

One other variant of building in brick is the example in Plate 75 where the corners have been trimmed with stone quoins, and in the window heads, with a date stone reading 1888 A.D. in the gable. This house is to be found in Lindsay.

Plate 76, Duplex, Oakwood Details

As well as experimenting with materials there was one particular kind of housing that many nineteenth century residents found peculiar. This was row housing. Row housing was never very popular with Canadians. They expected to own a home of their own even if in town the neighbour’s house was only a few feet away. But certain numbers of workers did have to live in duplexes, as in Oakwood in Plate 76 (note the pierced brickwork in the gables for ventilation)

Ventilation detail, Duplex, Oakwood Details

Plate 77, Wellington Street, Lindsay, row houses Details

or in row housing like that in Lindsay in the 1870s (Plate 77). This last example is rather unusual in being so early. Most row housing, even in built up areas like Whitby and Oshawa, dates to the 1880s and 90s.

Cambridge Street North, Lindsay, private dwelling

Details

As we can see from reviewing these various houses, a mixing of styles was the common denominator of town building. This borrowing of styles reflected a changed perception of the artistic function of architecture. Instead of building for certain aesthetic constants such as proportion and honest handling of materials, regardless of style, Victorian architecture was overlaid with symbolic literary and religious associations. These associations were an expression of current social values, as easily perceived in the heavy and garish decorations of display in the parlour, to the point where materials and styles were indiscriminately mixed so long as an ‘effect’, i.e. an impression, was made on the viewer. Such a straining for endless variety, without reference to more solid, deeper aesthetic values, led by the end of the century to a formless sterility; a lessening of vitality as reflected in Lindsay’s row of developer’s narrow brick houses with few fanciful decorations.

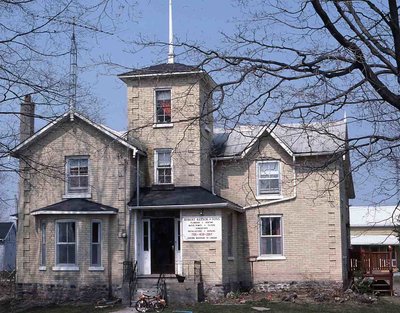

Plate 63, CKLY, Kent Street West, Lindsay Details

A few striking decorations did remain such as the curious practice of setting coloured stones, pieces of glass and mirror in a plastered gable end board as in Plate 63. But on the whole by the end of the century the imagination had failed.

Plate 86, Blacksmith shop, Argyle Details

In commercial architecture, however, there was a tremendous vitality. It is true that such artisan shops as the blacksmiths and livery stables (see Plates 86 and 87) were largely unadorned. But then they served almost purely utilitarian purposes.

Plate 87, Livery Stable, Woodville Details

Plate 78, Royal Bank of Canada, Kent Street West, Lindsay Details

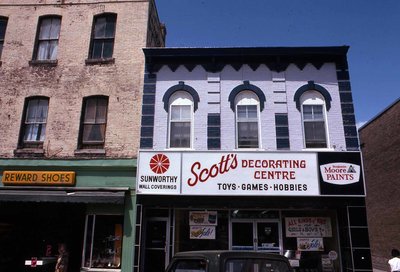

Commercial blocks were usually elaborately decorated through the medium of the prosaic brick in typical ‘drop’ style. For examples of this, see the commercial blocks in Lindsay (Plate 78 on Kent St. W., and

Plate 79, Downtown Lindsay Details

Plate 79 on Lindsay St. South).

Plate 90, King Street, Woodville Details

Another interesting variant was the use of zigzag brick patterns (see Plate 90 in Woodville), especially the upper storey. Here the commercial block has retained much of its nineteenth century street façade with deep windows and plain pillars. The original facades of most commercial blocks have been covered over with newer materials and by the ubiquitous neon sign.

Plate 80, Post Office Block, King Street, Omemee Details

One interesting stylistic variation of the commercial block was the Second Empire buildings in Omemee (see Plate 80). The Grandy Block was constructed in 1891 and later served to house Omemee’s post office. Note the full third storey mansard roof.

Shaw Research block, King Street, Omemee Details

The present Shaw research block across the street has a rather amusing false mansard roof only discernible from the rear of the building.

Royal Canadian Legion, Omemee Details

The present Legion is another example of this Second Empire influence though much larger. It was originally a machine foundry.

Downtown Lindsay Details

Most of these commercial blocks reveal traces of Italianate and Second Empire architectural influence. The degree of stylistic influence can be traced in part to the individual merchant’s preference and in part to these towns and villages great fires. In Lindsay’s case, the frame downtown core was consumed in the 1860s and 1870s and was subsequently rebuilt in brick. This explains to some extent the preponderate Italianate influence. Omemee, on the other hand, suffered its great fire in 1891 with the consequence of rebuilding a brick downtown in the light of the then popular architectural style; namely French Second Empire.

Plate 83, Royal Hotel, Argyle Details

Smaller villages of the area have retained not only their commercial blocks but also many of their hotels, artisan shops and village stores with their own architectural peculiarities. Surprisingly, many hotels have survived down to the present. The hotel and local tavern, once as familiar as the local gas station, served an essential purpose in Victoria’s transportation system. They provided shelter to travellers limited by the slow progress of the horse and the railroads which touched only the larger concentrations of population. In short, travel was time consuming and often difficult. The hotel, and its frequency, played a necessary part in this slower system of transport and, in particular economies like the lumbering in North and East Victoria, providing essential accommodation for a transient or seasonal work force.

Plate 82, Lucas Hotel, Downeyville, Emily Township Details

We have some particularly fine and early examples of the hotel in the county. In Downeyville there is the small, brick Lucas Hotel (Plate 82). In Argyle there is the very large and, until recently, elaborately decorated, Royal Hotel (Plate 83) and, in Lindsay, the renovated Grand Hotel (Plate 85).

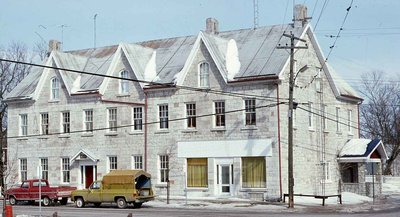

Plate 84, Verulam Lodge, Bobcaygeon Details

A rather unusual variant is the Temperance Hotel (Plate 84) in Bobcaygeon built in 1871 by Scottish masons working on the Trent Canal. This is a very large and impressive building in itself.

Plate 87, Blacksmith shop, Argyle Details

Other commercial buildings that local residents were quite familiar with were the artisan shops. These consisted of such buildings as blacksmith shops, a stone one in Fenelon Falls and a frame one in Argyle (Plate 86), built in 1895, a livery stable (Plate 87 in Woodville), a tailor shop in Cresswell, and harness and saddle shops to name but a few. These small shops, while usually of little architectural interest, played a vital part in Victoria’s urban development.

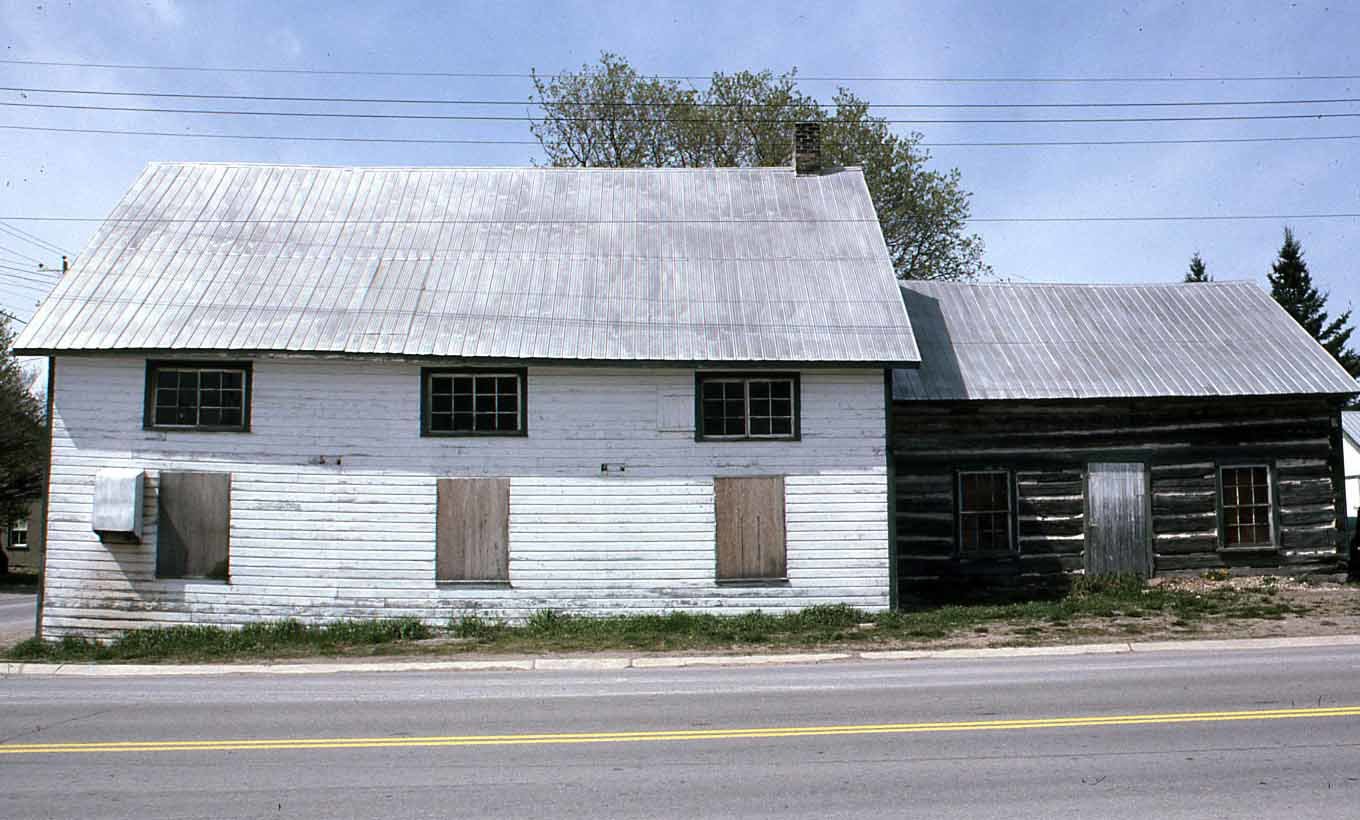

Plate 88, General Store, Oakwood Details

Of more architectural interest, perhaps, were the village stores. These often were built in L shaped designs with the receded section serving as the house while the projecting served as the store. There are good examples of this practice in Oakwood (Plate 88), Bolsover and Cambray.

Plate 89, General Store, Victoria Road, Bexley Township Details

There were, of course, more regularly shaped ones with elaborate store fronts as one can see in the example from Victoria Road (Plate 89). This village has many interesting examples of early stores basically because time has stood still for this community.

Plate 91, Horn Brothers Woolen Mills, Lindsay Details

One last type of urban building that must be considered is the factory. Here in Plate 91 we have the Horn Brothers Woollen mill in Lindsay. Even in its grimy appearance certain items of architectural interest can be found. Its unadorned use of iron pillar construction and brick infill for the walls is plainly expressed on its exterior. This plain exterior, in turn, tells us something more about urban Victorian building.

Factory buildings like this, which serve no apparent aesthetic purpose if we narrowly conceive the term aesthetic to cover only the idea of beauty, can serve to express an aesthetic purpose if we are willing to develop a wider perspective on the cultural implications of all buildings and not just the largest or most beautiful. This building expressed a disciplined, utilitarian, and often harsh, approach to the experience of work. This utilitarian aesthetic, it must be kept in mind, complemented the more romantic and fantastic world of High Gothic mansion building and its less affluent imitators.

Factory buildings like this, which serve no apparent aesthetic purpose if we narrowly conceive the term aesthetic to cover only the idea of beauty, can serve to express an aesthetic purpose if we are willing to develop a wider perspective on the cultural implications of all buildings and not just the largest or most beautiful. This building expressed a disciplined, utilitarian, and often harsh, approach to the experience of work. This utilitarian aesthetic, it must be kept in mind, complemented the more romantic and fantastic world of High Gothic mansion building and its less affluent imitators.

Thus there are a number of conflicting aesthetic experiences being expressed in Victorian urban building in the county. The play of greater commerce, wider cultural contacts with the outside (symbolized by the building of the Academy Opera House in the 1890s (Plate 92)), and the distinctions of class in the workplace, served to create a more sophisticated and, in general, a richer display of architecture in urban areas than in rural areas. This greater sophistication was a measure of Victoria’s growing prosperity and, with this prosperity, an indication of growing social complexity.