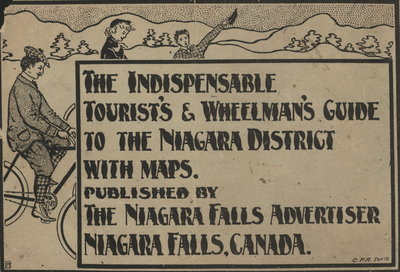

THE INDISPENSABLE TOURIST'S AND WHEELMAN'S GUIDE

TO THE NIAGARA DISTRICT,

WITH MAPS,

--BY-JAMES MAIN DIXON, F. R. S. EDIN.

[PUBLISHED BY THE NIAGARA FALLS ADVERTISER, NIAGARA FALLS, CANADA.]

TO NIAGARA.

Flow on forever, in thy glorious robe

Of terror and of beauty. Yea, flow on

Unfathom'd and resistless. God hath set

His rainbow on thy forehead, and the cloud

Mantled around thy feet. And He doth give

Thy voice of thunder power to speak of Him

Eternally,--bidding the lip of man

Keep silent,--and upon thy rocky altar pour

Incense of awe-struck praise.

--MRS. SIGOURNEY.

Entered according to Act of the Parliament of Canada, in the year 1899, by the Niagara Falls Advertiser? at the Department of Agriculture,

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1899, by the Niagara Falls Advertiser, in the office of the librarian of Congress, at Washington.

CONTENTS.

I. Preface 2

II. Hints to Wheelmen 3

III.Niagara Falls, N. Y. 4

IV. Niagara Falls, Ont .. 6

(1) Niagara Falls.: 6

(2) Niagara Falls Centre 6

(3) Niagara Falls South 6

(4) Queen Victoria Niagara Falls Park... 6

V.Facts about the Falls 7

VI. Notable Incidents Connected with the Falls. 7

VII. The Niagara District 8

ROUTE TABLES.

I. By Dufferin Islands and Falls View 9

II. To Beaverdams and DeCew Falls 9

III.To Montrose and Chippawa 10

IV. To Stamford 10

V. To Brock's Monument and St. Davids 10

VI. To Queenston and Niagara-on-the-Lake 10

VII. To St. Catharines 10

VIII. To Ridgeway and Fort Erie 10

IX. To Indian Village 10

X. To Lewiston and Fort Niagara 11

XI. To LaSalle and Fort Gray 11

XII. To Buffalo 11

DESCRIPTION OF ROUTES.

I. Through and about Victoria Park 11

II. To Beaverdams and DeCew Falls, by way of Lundy's Lane 12

III. To Montrose and Chippawa, by Lundy’s Lane,

returning by Victoria Park 13

IV. To Stamford 14

V. To Brock's Monument and St. Davids 15

VI. To Niagara-on-the-Lake 17

VII. To St. Catharines and neighborhood 18

VIII. To Ridgeway and Fort Erie 18

IX. To Indian Village 20

X. To Lewiston and Fort Niagara. 21

XI. To LaSalle and Fort Gray 22

XII. To Buffalo and back 23

Prefatory Note to Appendixes 25

APPENDIXES. ALPHABETICALLY ARRANGED.

1. Beaverdams, Battle of 26

2. Buffalo and Neighborhood 27

3. Chippawa, Battle of 28

4. Devil's Hole, Massacre at the 29

5. Fenian Invasion, The, of 1866 29

6. Lundy's Lane, Battle of 30

7. Lundy's Lane Cemetery (with map) 33

8. Lundy's Lane Observatory and Museum 36

9. Niagara, History of Old 36

10. Queenston Heights, Battle of 38

11. Rebellion, The, of 1837 40

12. Stoney Creek, Battle of 41

13. Welland Canal, The 42

MAPS.

1. Niagara District

2. Lundy's Lane Cemetery 34

3. Niagara Falls, (N.Y. and Ont.) 44

PREFACE

The unique natural and historic attractions of the Niagara District make it a paradise for the summer visitor; and yet many of the hundreds of thousands who visit it annually depart after having seen but a fraction of these attractions. The present work grew out of the realization that the wants of the intelligent visitor were not sufficiently catered to. As the product of much active rambling and pleasant research, it is now humbly offered by an enthusiastic wheelman and pedestrian to wheelmen and pedestrians. To those who prefer the aid of a horse in locomotion it should prove equally useful.

Mr. C. H. Mitchell, town engineer, Niagara Falls, Ont., has been very kind in preparing my rough-draft maps for the engraver.

In a preparatory note to the Appendixes I have acknowledged my indebtedness for historic material.

On the wonderful beauties of the Cataract and Rapids I have not expatiated—they appeal to everyone. Nor do they lessen with time and familiarity, but rather does the fascination grow.

~~J- M-D

St. Louis, Mo., January, 1899.

Hints to Wheelmen.

There are very few restrictions upon cycling either on the New York or Ontario side of the Falls. On the Ontario side, when the roadway is not good, no objection is made to riding on the sidewalks, so long as passengers are politely warned, and afterwards thanked for making way. This does not apply to other Canadian townships, where the sidewalks are strictly reserved for pedestrians. In Buffalo, a city of wheelmen, various regulations are strictly enforced-such as keeping to the right of the roadway, etc.

Members of the League of American Wheelmen are allowed to take their wheels into Canada free of duty. Other wheelmen are charged a duty of 30 per cent on the estimated value, the money being returned when the visit is over.

So far as my own experience of the climate goes, it [?] much more than it rains.

Niagara Falls, N. Y.

Most visitors to the great Falls arrive at the railway station situated at the corner of Falls and Second streets. There is also another railway station one block north, on Second and Niagara streets, by which N. Y. L. E- & W. and Wabash trains come in. The first station is only four blocks and the second only five distant from the State Park. Electric cars pass both stations, some taking to the Union Station at the lower R. R. bridges, by Main street, others leaving Main street one block north of Niagara street and descending into the gorge for Lewiston. At the park end of Falls street there is a soldiers' monument, erected in 1876. From this point the above two electric lines start; and also the electric cars for Buffalo, every 15 minutes' Baggage cars (carrying bicycles) leave at 8 and 11.30 a. m. and 2.30 and 5 p.m.; baggage can be checked at any time Fare to Buffalo, 35c; return (unlimited) 50c. Gorge route cars: Fare to Lewiston, 30c; to Youngstown and Fort Niagara, 50c; round trip to Lewiston, returning on Canadian side, 75c.

Close to the monument, at the corner of Falls and Canal streets, and immediately above the upper bridge, is the huge observatory tower with elevator. Those anxious to have a bird's eye view of the neighborhood will have their wish gratified here; admission, 50c.

Stretching along the bank of the river, from the hydraulic canal to the upper bridge, is the New York State Reservation Park, opened to the public in July, 1885. It is about 107 acres in extent and is beautifully laid out. The portion between the American Falls and the upper bridge is known as the Grove.

Since the opening of the park the Falls can be visited without fear of extortion. The superintendent of the reservation exercises a control over hackmen; there are established fares, and visitors who are fleeced have themselves to blame. At the corner of the Grove, beside an archway, is the superintendent's office. Ask here for the map and guide, a folder furnished free of charge to all visitors. This map gives a bird's eye view of the American and Canadian parks, with the Falls between. On the back of the folder there is a small but useful historic map of the river. The rest of the back contains printed matter of the utmost value to visitors.

Along the city side of the grove will be noticed Indian women from the Tuscarora Reservation (See Route XI) vending moccasins, pincushions and other fancy articles. Within the Grove are picnic grounds, a cascade fountain with drinking fountain beside it, a pavilion, hall and library. Just below the library, and close to the upper bridge, is the platform known as Hennepin's View. Further up the bank is the Inclined Railway, which conducts to the steamboat landing below. Here passengers get on board "The Maid of the Mist" (fare, 50 cents). There is a fee of 10 cents for conveying visitors up and down the Inclined Railway; but the use of the stairs is free (251 steps.)

Close to the Inclined Railway is Prospect Point, a stone platform at the corner of the Grove, washed by the waters of the Niagara, as they slip over the precipice. This is a view which fascinates visitors. Turn to the left and proceed up the bank of the stream in full view of the rapids and the islands beyond. At the edge of the American fall, across from Prospect Pt., is Luna I, reached from the large island by a bridge, and above it are Crow I., Blackbird I., and Robinson's I. At the upper end, in full view of the shore, there is a rock, known as Avery's Rock.

Here on the morning of July 19, 1853, a man was seen, who had been drawn into the rapids when crossing with a companion from Chippawa. Boats and ropes were lowered, and many unavailing attempts were made to rescue him. Finally in attempting to get on a raft that had been floated down, he fell into the river and was drowned, after an hour's struggle for life..

The bridge to the large island is soon reached. The present bridge was built in 1856 to replace a wooden structure of 1818. In 1817 the first bridge was built, but was washed away in the winter. The first four spans conduct to Bath Island, once .covered with unsightly mills. The two small islands above it are known as Ship Island and Brig Island. Two more spans land one on Goat Island, now 6£ acres in extent; it was formerly said to contain 250 acres.

It received its present name from the circumstance that some goats were placed upon it; they died, however, during the severe winter of 1779-80. Thirty-six years later it became the property of General Porter (see Appendix 6). There is delightful wheeling as well as walking round and about the island. Turning to the left one finds at the foot of the stone steps a well of the finest water. Rounding the southeast corner, you come to the pavilion. Close by are the steps leading down to the Three Sisters Islands, connected with Goat Island in 1868 by strong suspension bridges. Little Brother Island lies just below the third Sister Island. You are now in the magnificent Canadian rapids.

Under the first Sister Island bridge is what is known as the Hermit's Cascade. Here in 1829 an accomplished youth, named Francis Abbott, an Englishman, known since as the Hermit of the Falls, used to bathe. He lived in a hut near the spot for two years. In 1831 he was drowned, while bathing near the foot of the Inclined Railway.

Out in the rapids, about midway across, note the remains of Gull Island, so late as 1840 covering two acres.

Continue down to the Horseshoe Falls and find the stairway leading to the bridge, which conducts to Terrapin Park, the best scenic point on the American side. From 1833 to 1873 there stood here the old Terrapin Tower (or "Horseshoe" or "Prospect"), built of stones gathered in the vicinity. It was considered unsafe and was pulled down. Formerly a piece of timber used to jut out at this point, over the precipice. On it Francis Abbott was constantly seen, walking fearlessly back and forth at all hours of the night. In the winter of 1852, a visitor from West Troy, N. Y., slipped from the bridge, and was happily caught between two rocks, whence he was rescued unconscious.

Returning to Goat Island and rounding the west side, you will come to the Biddle Stairs, erected by Nicholas Biddle, a Philadelphian banker, in 1829. These stairs conduct to the water's edge. The fee for a guide and oilcloth outfit is one dollar.

A plank walk leads to the Cave of the Winds, under the Central Fall, sometimes called Aeolus Cavern, and first entered in 1834. The air in the huge chamber is so compressed, by the falling water, as to make it resemble the abode of Aeolus:

" Hie vasto rex Aeolus antro, Luetantes ventos tempestatesque sonoras, Imperio premit ac vinclis et earcerefrenat."

There are splendid rainbow effects in the afternoon, when the sun is shining. The visit is more or less a wet one, according to the direction of the wind.

Remounting the stairs, pass by Stedman's Bluff, where a great landslip occurred in 1847, and go on to Luna Island, descending to the bridge either by stone steps or by a winding pathway. The bridge crosses the rapids above Central or Luna Fall. The views from Luna Island are particularly fine. Return from Luna Island to the bridge, and thence make a tour of the park, as far as the Hydraulic Canal.

The city is a bustling one, with mills, breweries, dime museums and gay bazaars. The streets are well-paved with asphalt or vitrified brick. Three bridges connect with the Canadian shore :

1. The upper bridge, once a suspension bridge, but converted into an arched bridge in 1898. Fare for crossing, 10 cents; return (the same day) 15 cents. Passengers have the option of riding on an electric car, which runs every few minutes. The first bridge, built in 1872, fell in the great storm of Jan. 10, 1889.

2. The Michigan Central cantilever bridge, a graceful structure, at the lower end of the town--for railroad traffic only.

3. The Grand Trunk arched bridge (formerly suspension), with foot and carriage way beneath the railroad tracks. Fare, 10 cents; return (same day) free.

Immediately below No. 3 on the river bank are the grounds of DeVeaux College, an educational establishment under Episcopal auspices.

The lower rapids and whirlpool are best seen by taking the Gorge route down to Lewiston and returning by the Queenston electric railway.

Niagara Falls, Ontario.

This expression divides itself at once into four:

1. The town of Niagara Falls, formerly known as Clifton, and still so designated by the Michigan Central R'y Co. One block south of the large G. T. R. station on Bridge Street is the M. C. R. "Clifton" station, used also by the St. Catharines and Niagara Central R'y; here they keep central time, one hour slow. The offices and chief station of the Niagara Falls Park and River Electric R'y are at the foot of Bridge Street. Ask for their folder; it gives useful information and a scenic map; bicycles are allowed on all the cars free of charge Rates for tourists: Bridge Street to Queenston, 25 cents; round trip (same day) 40 cents; to upper bridge, 10 cents; to Chippawa, 20 cents, round trip (same day) 35 cents. To residents (summer or permanent) tickets at a considerable reduction are sold at this office.

One block south from Bridge Street, on Clifton Avenue, is the handsome post office and customs building. On Erie Avenue, one block west of the post office, are the principal offices and stores. Clifton Avenue meets the river road at the Episcopal Church. Recent improvements have made of this a very fine highway.

A horse car leaves Bridge Street every 40 minutes for Niagara Falls Centre and South by way of Erie (south) and Queen (west), Welland Avenue (south), Morrison (west), St. Lawrence Avenue (south), Simcoe (west) and Victoria Avenue (south) to Ferry Road (west), with south terminus a few blocks south of Lundy's Lane.

2. Niagara Falls Centre, with post office on Centre Street, one block west from M. C. "Niagara Falls" station. Here the Oneida Community (represented also on the N. Y. side) have a factory and several community halls. At the foot of the hill leading from the M. C. R'y station stood the Clifton House, burnt to the ground in 1898. To the north on high ground bordering on Victoria Avenue and the Michigan Central R'y tracks is (or was) Wesley Park, intended for summer social religious gatherings. It has, however, failed to perpetuate itself.

3. Niagara Falls South, formerly called Drummondville, after Sir Gordon Drummond, who commanded the British forces at the battle of Lundy's Lane, served later as an administrator, and died in London, in 1857, at the ripe age of 82. The village is situated at the junction of Lundy's Lane with the Chippawa and St. David's Portage Road. (See Appendixes 6, 7, and 8).

4. Queen Victoria Niagara Falls Park covers an area of 154 acres, and extends along the west bank of the Niagara River for two and a half miles. The southern entrance is one block north of the upper bridge. There belongs to the park, in addition, a strip of land 50 feet wide, stretching along the river bank as far as Queenston. The park is open free of charge to all, and there are no restrictions on wheeling. Throughout the grounds are many drinking fountains, and pleasant arbours. There are two exits to the west, one known as the Jelly Cut (a very steep pathway), and the other as the Murray Street Ravine, leading up to the Falls View railway station of the M. C. railway. This is a carriage way, but too steep for wheeling. Both conduct to the open meadows, south of All Saints" church, Niagara Falls South. (See Route I).

The most interesting spot in the park used to be Table Rock, a huge platform extending over the river, about ten rods below the Falls. It kept rapidly diminishing in size during the century. In July, 1818, a huge mass, 160x35, broke off. Ten years later three immense bits fell with a great concussion; and in the following year another mass fell in; again in 1850 a huge piece, 200x60 feet, gave way, and finally, by order of the government, the remainder, being considered unsafe, was exploded. The fragments lie in the river below. Mrs. Sigourney wrote, on Table Rock, her "Apostrophe to Niagara." This is the traditional spot for going down under the Falls. An elevator (25 cents) is at the service of visitors, and another quarter sucures the use of an oil-cloth suit from Table Rock House close by. The descent fully repays one. Nowhere else is so overpowering an impression conveyed of the power and beauty of the cataract. Where the path ends a tunnel, 150 feet in length, has been made so as to give the visitor a view of the inner side of the great sheet of water, as it descends in spray.

After passing the power house of the Niagara Falls Park and River Railway one comes to Cedar Island and the south end of the park, admission to which formerly cost 10 cents--now no longer demanded. For the rest of the attractions see Route I.

Facts About the Falls.

Height of the Horseshoe fall, 158 feet. Height of the American fall, 167 feet. Width of American fall, 1660 feet. Average depth of river from Lake Erie to the falls, 20 feet.

Depth between the falls and the whirlpool, 75 to 200 feet.

Depth of the whirlpool, 400 feet.

Estimated volume of water passing over the falls per minute, 18,000,000 cubic feet.

Minimum annual rate of recession of the Horseshoe fall, 24 feet.

Actual recession between 1842 and 1886, 300 feet.

The famous ice bridge, as it is called, which forms in winters, is really a large ice flow, which is upheaved from the great pressure. The ice mountain forms below the American fall and is a huge cap of frozen spray covering the boulders.

The recession of the American fall is trifling. No human being has ever gone over the falls and survived.

Notable Incidents Connected with the Falls.

Sam Patch jumped twice from a platform 97 feet above the river, under Goat Island, 1829.

Blondin crossed the chasm on a tight rope carrying his manager, Harry Calcourt, on his back, Aug. 17, 1859.

Blondin performed before the Prince of Wales, 1860.

Joel Robinson piloted the Maid of the Mist, with engineer on board, through the gorge right to Queenston in order to sell the vessel, 1861.

Bellini performed on a tight rope which was stretched from Prospect Park to the Ferry landing, and twice jumped into the river, being nearly drowned on the third occasion, 1873.

Stephen Peere gave performances on a steel cable below the G. T. R. bridge, 1878.

Capt. Matthew Webb was drowned in swimming down the whirlpool rapids without the aid of a life preserver, July 24, 1883.

DeWitt lost his life trying to climb the ice-mountain alone, Feb. 28, 1886.

Carlisle Graham navigated the whirlpool in a barrel (elaborately constructed), July 11, 1886.

Messrs. Potts and Hazlitt also navigated it in a barrel, Aug. 19, 1886.

Mr. Potts and Miss Sadie Allen navigated it together, in a barrel, 1886.

Kendall, a Boston policeman, wearing a life preserver, swam the rapids to the whirlpool. Aug. 22, 1886.

Lawrence Donovan jumped from the upper suspension bridge, breaking a rib, Nov. 17, 1886.

Stephen Peere was drowned, while performing, June 25, 1887.

Chas, A. Percy navigated the whirlpool in a life-boat of his construction, Aug. 28, 1887.

Robert Hack attempted to navigate the whirlpool, strapped in a life-boat, but was drowned and his body mangled, July 4, 1888.

Samuel Dixon crossed the gorge on Feere's wire, per-forming some acrobatic feats on the passage, Sept. 6, 189

The Niagara District.

When the white man first began to push westward to the great chain of lakes, which are so striking a feature of the physiography of the continent, a tribe of Indians, known as the Neutral Nation, lived on the banks of the Niagara river. They were called Neutrals because they were neither a Huron nor an Iroquois tribe, but were friendly to both of these powerful confederations. The name Niagara, originally Onghiara, was given to this fishing settlement at the mouth of the river, on the site of the present Niagara-on-She-Lake. It is the sole word which survives of the language. The accent falls properly on the middle a. Goldsmith's lines in "The Traveller," therefore, which require this pronunciation, register the earlier use:

“Where wild Oswego spreads his swamps around, And Niagara stuns with thundering sound.”

Father Hennepin is said to have been the first to spell the word in the modern way: and it appears so far for the first time in cartography in Coronelli's map, published in 1688. Above the falls the river seems to have been considered part of Lake Erie.

The Neutral Nation was finally exterminated about 1650 by the Iroquois. The Seneca branch of this tribe then took possession of the eastern side, while the Mississaugas. of the great Chippawa nation, settled on the Canadian side. Their name survives in Fort Mississauga, situated at the entrance to the Niagara river, opposite Fort Niagara. This tribe were better fishermen than hunters.

There has survived an interesting story of early Indian days, which reminds me of the old Andromeda legend. Every year the fairest maiden of the tribe was given as a propitiatory victim to the deity of the cataract. Gaily arrayed, and sitting erect in a white birch bark canoe, she launched into the rapids and was borne swiftly, like a feather, over the edge of the cataract into the boiling cauldron beneath. The death, so far from being shunned by the girls of the tribe, was eagerly coveted as a distinction. On the last occasion of the observance of this rite, as the canoe of the maiden darted forward to its fate, another canoe was seen to follow it. The occupant was no other than the girl's father, the much-trusted chief of the tribe. The sacrifice of his valuable life seemed too great, and the practice was henceforth abandoned.

The first white man to ascend the Niagara river and behold the Falls was probably Father Hennepin, who had been dispatched by the enterprising La Salle, with a number of artizans, to construct a boat for the navigation of the upper lakes. It was in the winter of 1678, that he landed in Lewiston and disembarked his stores. Then he ascended what he named "the three mountains," or triple terrace, on the right bank of the river. His description of the Falls has often been quoted. For the story of the Building of the Griffon, near the present village of La Salle, see Route XL

Few districts have suffered more from a change of nomenclature. We subjoin below a list of some of the changes:

Black Creek………………..Frenchman's Creek

Buffalo ………………………New Amsterdam

Crowland……………………Cook's Mills

Dufferin Islands ………….Clark Hill Islands

Goat Island………………….Iris Island

Lake Ontario……………….Lake St. Louis

Navy Island………………….Isle de Marine

Niagara Falls, N. Y……….Grand Niagara; Manchester

Niagara Falls, Ont. ……………Clifton

Niagara Falls South…………..Drummondville

Niagara-on-the-Lake…………Butlersburg ; West Niagara ; Newark

Schlosser (Fort)……………….. Fort de Portage; Little Niagara

Ussher's Creek…………………..Street's Creek

The French control of the district ceased in 1759 with the fall of Quebec and the capture of Fort Niagara. The garrison at Fort de Portage, afraid lest their vessels should fall into the hands of the British, conveyed them across the channel and set fire to them at the south end of Grand Island, at a place known still as Burnt Ship Bay.

The history of the western shore began with the American Revolution. It was for the most part colonized by sturdy and excellent United Empire Loyalists, noted for their peaceful home life and their great longevity. There was a minority of less excellent material which in the war or 1812 helped to bring troubles upon the community. But the pluck and patriotic zeal shown by the settlers as a whole--both men and women--in repelling an alien invasion and the imposition at the point of the bayonet of a flag and political system they disliked, may well recall the brightest pages of Scotch or Swiss history. At the close of the war, instead of the fond dream of a Canadian frontier wiped out. there was, except at Amherstburg, a frontier line extended into the territory of the invaders. Americans may console themselves with the thought that many of their wisest statesmen passionately protested against this disastrous war. It was Canada's brilliant war of independence. For long it left intense bitterness on both sides of the frontier; but this feeling has grown weaker and weaker and is passing away altogether. Beth communities have prospered. The eastern shore of the Niagara river has its Erie canal; the western shore its Welland canal. On the American side the busy city of Buffalo, throbbing with electricity, drains the whole country side of its most active and ambitious youth. This industrial activity is characteristic of the right bank of the river down to Niagara Falls. The left bank is quiet and peaceful; a land »of peach orchards for the most part. Its fruit at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia and later at the Chicago World's Fair took from 70 to 90 p. c. of the awards. The Stars and Stripes and the Union Jack wave over happy and prosperous communities; there is room for emulation, but no room for hatred or mischievous jealousy.

ROUTES.

ROUTE 1.

(By Dufferin Islands and Falls View)

Niagara Falls Centre to Old Burning Spring, by way of Dufferin Islands….. 3.5 Miles.

Old Burning Spring to Niagara Falls Centre, by way of Loretto Convent…..2.7 Miles.

ROUTE 2.

Niagara Falls Centre to Lundy's Lane Observatory…………………….1.0

Lundy's Lane Observatory to Allanburgh …………………………………..5.6

Allanburgh to Beaverdams…………………………………………………………2.3

Beaverdams to DeCew Falls……………………………………………………….2.9

DeCew Falls to Thorold……………………………………………………………….3.8

Thorold to Niagara Falls Centre…………………………………………………..8.7

ROUTE 3.

To Montrose and Chippawa.

Niagara Falls Centre to Lundy Farm 2.4

Lundy Farm to Montrose Bridge 3.1

Montrose Bridge to Welland Road 2.3

By Welland Road to Chippawa Bridge 1.8

Chippawa Bridge to South Park Entrance 1.2

South Park Entrance to Victoria, Falls Centre 2.8

ROUTE IV.

To Stamford by way of Lundy's Lane.

Niagara Falls Centre to Niagara Falls South 9

Niagara Falls South to Southend 1.8

Southend to Stamford 9

Stamford to Monument Road 1.0

By Monument Road to Cemetery 1.6

Cemetery to Grand Trunk Bridge 1.3

Grand Trunk Bridge to Niagara Falls Centre 1.9

ROUTE V.

To Brock's Monument and St. David's.

Niagara Falls Centre to Fairview Cemetery 2.0

Fairview Cemetery to Brock's Monument 4.7

Brock's Monument to St. David's 3.1

St. David's to Stamford 2.4

Stamford to Niagara Falls South 2.7

Niagara Falls South to Niagara Falls Centre 9

ROUTE VI.

To Niagara-on-the-Lake.

Niagara Falls Centre to Fairview Cemetery 2.0

Fairview Cemetery to Brock's Monument 4.7

Brock's Monument to Niagara-on-the-Lake 7.6

Niagara-on-the-Lake to Virgil 4.0

Virgil to St. David's 5.8

St. David's to Niagara Falls Centre 6.0

ROUTE 7.

To St. Catharines.

Niagara Falls Centre to Thorold 8.7

Thorold to St. Catharines 5.3

St. Catharines to Homer 3.0

Homer to St. David's 5.0

St. David's to Niagara Falls Centre 6.0

St. Catharines to Port Dalhousie 3.0

St. Catharines to Stony Creek 31.0

St. Catharines to Niagara-on-the-Lake 12.0

ROUTE 8.

To Ridgeway and Fort Erie.

Niagara Falls Centre to Stevensville 11.4

Stevensville to Ridgeway 4.5

Ridgeway to Fort Erie Village, by way of the old fort 7.6

Fort Erie Village to Slater's wharf 14.4

Slater's^ wharf to Niagara Falls Centre 5.0

ROUTE 9.

To Indian Village.

Niagara Falls Centre to Grand Trunk R. R. bridge.. 1.9

Grand Trunk R.R. bridge to corner of Ontario and

Lockport St., Niagara Falls, N.Y 8

Corner of Lockport and Ontario St. to Military Road

crossing 3.5

Military Road crossing to Reservation schoolhouse.. 5.3

Reservation schoolhouse to river road 5.4

By river road to Grand Trunk bridge 3 3

Grand Trunk bridge to Niagara Falls Centre 1.9

ROUTE 10.

To Lewiston and Fort Niagara.

Niagara Falls Centre to Grand Trunk bridge, east end 2.0

Grand Trunk bridge to Lewiston 5.4

Lewiston to Youngstown P. O 6.0

Youngstown P. O. to Fort Niagara 1.5

ROUTE 11.

La Salle and Fort Gray.

Upper Bridge to La Salle bridge 6.1

La Salle to Lewiston Heights 7.5

Lewiston Heights to upper bridge. 5.3

ROUTE 12.

To Buffalo.

From upper bridge to La Salle P. 0 5.8

La Salle P.O. to Tonawanda P. O 6.5

Tonawanda P.O. to Forest Lawn Cemetery 6.9

forest Lawn Cemetery to corner of Main St. and Genessee St 32

Route I.

THROUGH AND ABOUT VICTORIA PARK.

This makes a pleasant morning or afternoon ride. There are no restrictions laid upon riders in the Park--the footpaths and board for walks are free to use. On entering by the north gate one comes immediately to a pretty brick cottage, the office of the Park superintendent. Here are sold the valuable publications of the Lundy's Lane Historical Society. Various summer houses along the route invite one to linger--beginning with the Rambler's Rest, and, a short distance beyond, Inspiration Point. At the Horseshoe Fall, except with a west wind, there is apt to be a short bit of very wet riding; but the rainbows formed in the afternoon are very lovely. Passing along Cedar Island, opposite a house on the other side of the electric railway track, is a fountain of fine spring water. Before reaching the bridge at Dufferin Islands stop off at a summer house, where is the best view of the beautiful White Horse Rapids --a cool spot on the warmest days. Behind it is an old building with disused mill-race, the remains of Bridgewater or Street's Mills. Behind is Clark's Hill, on which one of the Clark family built a residence. The first name borne by Dufferin Islands was Clark's Hill Islands. The elder Clark, a partner of Samuel Street, came loyally to the aid of General Drummond in 1814 with funds which allowed him to continue operations and fight the battle of Lundy's Lane. Their mills were burnt by General Ripley in his precipitate retreat to Fort Erie after the battle. This place gave the American name to the battle.

After crossing the first bridge one can turn in to the larger island by the board walk known as The Lover's Walk. Wheel through the woodland paths of the island and leave by the small suspension bridge to the south. This conducts to the south shore of the "Elbow." The circuit of the Elbow can then be made by a good gravel path on the water's edge, a cool and beautiful short ride. Leaving the path at the south-east end, ascend the hill road to the right, and turn east along the brow of the hill, by a roughish grassy track, to the summer house above the electric railway. Here there is a tine view of the rapids; behind is to be noticed the village church of Chippawa, backed by the village groves and cottages. Returning, keep to the brow of the hill, pass the Old Burning Spring house on the right or left, enter the Portage Road and continue west for a short way, then turn north. On the right will be noticed the entrance to the Clark residence. The red roof of the new Convent building is now visible ahead. Cross two railway tracks after the road bends west, and then resume a northerly direction. The massive buildings of the Loretto Convent of Our Lady of Peace, are passed on the right. This convent was founded in 1860, from Toronto, the order having crossed in 1845 from Dalkey Abbey in Ireland. Pope Pius IX granted the privilege of pilgrimage to this convent; it is for the most part an educational establishment. Turn in on reaching its north wall and you will come to a fence overlooking the Michigan Central Railway. From this point is gained the finest general view of the Falls. The whole grand sweep of the river as it approaches the rapids is taken in ; below are the boiling Horseshoe Falls; to the left, in full view, the white breadth of the American Falls.

In returning it is best to cross the common by one of the tracks leading to the Ferry Road and Victoria Avenue. The Portage Road conducts to Niagara Falls South and Lundy's Lane.

Route II.

TO BEAVERDAMS AND DECEW FALLS, BY WAY OF LUNDY'S LANE.

Leaving Niagara Falls Centre (Michigan Central Railway station) go due south a few hundred yards to the end of Victoria Avenue, then turn west along Ferry road at Drummondville, called after Gen. Gordon Drummond, and now known as Niagara Falls South. Here the old Portage road from St. Davids and Stamford to Chippawa crosses at right angles. Continue up the ascent to Lundy's Lane Observatory, on the right hand, at the summit of the; slope. (See Appendix VIII -- Lundy's Lane Observatory and Museum). Across the road stands a brick Presbyterian church, and adjoining it on the left is a graveyard, containing a handsome monument to the heroes of the battle fought here on the 25th of July, 1814. [See Appendix VI-- Battle of Lundy's Lane (or Bridgewater.) ] There are numerous interesting graves in the cemetery. (See Appendix VII--Lundy's Lane Cemetery.)

Continuing due west wheelmen and pedestrians will enjoy a shady side-path on the left, extending about a mile and a half. Thence four miles of stone road to Allan-burg. (A shorter clay road, the real continuation of Lundy's Lane, leaves the stone road just beyond the crossing of the road to Montrose, at the Lundy farm, in a northwesterly direction. Some will prefer this road.) At Allan-burg turn north on the Thorold road for 1 7-10 miles, then west again on a rough clay road, across the Welland canal, to Beaverdams, situated round a hollow. (See Appendix I --Battle of Beaverdams.) On the crest of the ascent from the hollow runs a road from Thorold, in a southerly direction; cross this and continue on the rough clay road, past a smithy and the recently built aqueduct of the Cataract Power Company, on the left, to the interesting old stone DeCew House, which is on the right of the road. (See Appendix I.) Thence to the mill at DeCew Falls.

These tine Falls, were they not dwarfed by their giant neighbors, would attract considerable attention. The volume of water is by no means inconsiderable, and the height of the upper falls must be at least 75 feet. A wooden turret with staircase (admission 10 cents) admits to the upper pool. Here the surroundings remind one of a lovely highland glen. A footpath leads to the lower falls, a few hundred feet down.

In returning, take the road which comes in at the mill from the north, and follow it to Thorold-fair wheeling. Cross the canal and, entering the Main street, follow it to the right, ascending. It makes two sharp turns, one to the left, another to the right. The last branch of the canal is crossed in leaving the town. A large swing bridge, carrying the railway track over the canal, will be observed a few hundred yards to the right. Follow the stone road until it approaches the track, then enter a field on the right, making for the east end of the bridge, and a few steps bring you to a broad, low obelisk, bearing the inscription:

“Beaverdams, 24th June, 1813."

During the excavations which accompanied the construction of the canal, a number of bones were dug up near this spot, supposed to belong to the Americans, who fell when Col. Boerstler surrendered. About eighty of his detachment were killed or wounded, and the contractor generously erected the obelisk to the memory of the dead.

Returning to the stone road one goes due east for about three miles, and then turns south, on an excellent country road, crossing two railway tracks. A short two miles brings one in to Lundy's Lane, at a little schoolhouse, with cemetery adjoining. Thence two miles and a half to the starting point.

Route III.

TO MONTROSE AND CHIPPAWA BY LUNDY'S LANE, RETURNING BY QUEEN VICTORIA PARK.

Take the Lundy's Lane route as in Route II; at the Lundy farm, about a mile and a half beyond the Observatory, turn to the left and follow due south for about two 13 miles. There the road takes a slight turn to the east. Continue for half a mile further, when the Montrose hotel will be observed somewhat to the right. South of the hotel is a bridge over the Chippawa or Welland River, a lazy stream about 200 feet wide. About three-quarters of a mile further on turn east towards Chippawa. Continuing about a mile or more on the same road until Lyon's Creek is reached, one finds the site of Misener's House, the headquarters of the British commander in the action of Cook's Mills, Oct. 19, 1814, where the Canadian Glengarry regiment greatly distinguished itself. Further up Lyon's creek, on the Welland road, is Crowland, then known as Cook's Mills. The road will be found somewhat rough, particularly so at some places.

About a mile and a half beyond Montrose the cross road enters the Welland road, which trends more to the left and skirts the left bank of Lyon's creek. Another mile and a half brings one to a bridge over this creek just above its junction with the Chippawa. The bridge over the Chippawa is a mile further on.

This village was at one time a centre of trade and fashions in the Niagara district, but has lost its old prosperity. The battle of Chippawa was fought here, mostly between the bridge and Slater's dock, on the 5th July, 1814. (See Appendix III). The handsome brick mansion built by a Dr. Macklem, and conspicuous from the road, stands on the site of the battlefield. From Slater's dock, about a mile further on, just to the south of the mouth of the Chippawa river, a boat leaves twice a day for Buffalo, and there is a street car line connecting this with the Niagara Falls Park and River line, which has its terminus at Chippawa bridge. The car line and the road keep to the water's edge all the way--a roughish clay road. This spot is connected with the rebellion of 1837-8, (See Appendix XI). From the Chippawa bridge to the south entrance of the Victoria Park is an old macadam road, in ridges which make wheeling difficult except to the steadiest riders, but there is little over a mile of it. Through the park, where no restrictions whatever are placed upon bicyclists, the wheeling is delightful. When the wind is in certain quarters, however, the paths beside the cataract are very moist and dirty, and one is apt to get drenched. See Route 1.

Route IV.

TO STAMFORD.

This route gives a pleasant morning ride of about nine miles. Leave Niagara Falls Centre as in Route II. Turn north on entering the village of Drummondville into the Portage Road, and fine side-path wheeling will be found. Two wooden railway bridges are crossed. At Southend another road from the south comes in at a sharp angle and joins the Portage Road, where it is crossed by Thorold and St. Catharines stone roads. About three-quarters of a mile from Southend, on the right hand side, is Stamford Episcopal church, dedicated to St. John, and erected in 1825. The interior, with tine memorial windows, is worth visiting; the keys will be found next door. The building, of stone faced with plaster, was erected chiefly through the efforts of Sir Peregrine Maitland, a former Lieutenant-Governor of the Province and one of Wellington's bravest generals. He had a manor house in the neighborhood destroyed by tire many years ago [See Route Y] and was highly interested in the development of Stamford, for which he expected a great future. It is, as he left it, a quiet village altogether on the English model. In the quiet cemetery of St. John's are some interesting graves. There is a headstone to the memory of a gallant young man who fell in the Fenian raid of 1866: "Pro Patria ac Begina. John Hermann Mewburn, Toronto University Rifles, 2nd Battalion Queen's Own, only son of Harrison Chilton Mewburn and Emily his wife, killed at Limeridge, June 2nd, 1866, lighting in defence of his native land against Fenian invaders, aged 21 years." [For an account of this raid see Appendix V, "The Fenian Invasion of 1866.] Close by this is another headstone to the memory of four children of the Mewburn family, all of whom died of scarlet fever on the passage out to Quebec, and were buried in that city.

Crossing the triangular village green, and returning to the St. David's road, one will come immediately to the Presbyterian church, a modern frame building. There are some quaint inscriptions in the adjoining graveyard: "In memory of Andrew, son of Wm. and Mart. Murray, who died on the ocean, in his 5th year.

In memory of a loved one

Who was both true and kind,

For health upon the ocean

He sought but could not find."

Another headstone bears the following inscription: "In memory of James Middough, who departed this life June the 25th, 1839, aged 79 years, five months and fifteen days. Farewell my wife, my life is past, my love to you so long did last but now no sorrow for me take beloved my children for my sake."

There is a railway station to the north of Stamford on the Michigan Central line from Niagara-on-the-Lake to Buffalo.

In returning to the Fails take a road east, which will be found a short way beyond the Presbyterian church, and proceed for one mile, when it crosses the Brock's Monument road. [If one continues east he will reach Foster Flats, above the lower rapids, passing over the old course of the Niagara River. How it filled up between the Whirlpool and St. Davids is a mystery, but there is now little or no depression.] Turn south on the Brock's Monument road, cross a railway track, the Thorold road, and another railway track, and at Fairview cemetery turn east again. About half way down there is a short route by Victoria Avenue back to Niagara Falls Centre, passing the handsome Catholic church, a new building in brown stone. The road from Fairview cemetery is known as Chestnut Street as far as the St. Catharines railway track, and then becomes Bridge Street. It leads directly to the Grand Trunk Railway station, the bridge station of the Niagara Falls and River Electric Line, and the railway bridge, with carriage way and foot paths. Improvements are making of the riverfront an excellent roadway of the best macadam. It is almost exactly a mile and a half between the lower and upper bridges.

Route V.

TO BROCK'S MONUMENT AND ST. DAVIDS.

Follow Victoria Avenue northwards to Chestnut street, then turn due north for exactly two miles to the

meeting of five roads, just beyond the crossing of the M. C. R. R. and G. T. R. R. tracks, which run side by side at this point. Stamford Station on the former line is close by (see Route IV). At the meeting of the five roads there stands at the corner between the two roads on the right hand a house known as the Halfway House, with a pump or excellent drinking water in front. The second of the two roads to the right will take one direct to Brock's Monument, by a fairly good road, helped out for a mile by aside path. Enter the park round Brock's Monument by the south-east carriage way. This noble shaft is perhaps the finest isolated column, all things considered, in the world. The foundation rests on solid rock and is 40 feet square and 10 feet thick. Above it is a grooved pinth or sub-basement, 38 feet square and 27 feet high, with eastern entrance. On its angles are lions rampant, 7 feet high, supporting shields with the armorial bearings of the hero, and the motto beneath, "Vincit Veritas." Its north face carries the following inscription: "Upper Canada has dedicated this monument to the memory of the late Major General Sir Isaac Brock, K. B., Provincial Lieutenant-Governor and Commander of the Forces in this Province whose remains are deposited in the vaults beneath. Opposing the invading enemy, he fell in action near these heights on the 13th of October, 1812, in the 43rd year of his age, revered and lamented by the people whom he governed and deplored by the sovereign to whose service his life had been devoted." Round the base of the monument is a dwarf-wall enclosure, 75 feet square, with fosse on the interior. At the angles are massive military trophies, representing Roman armour, on pedestals of cut stone 20 feet high. A pedestal rests on the sub-basement, 16 feet square by 88 feet high, with three emblematic bas reliefs on the east, south and west sides, and on the north side an alto-rilievo representing the scene of the hero's death, as he led the 49th regiment to the assault. The fluted column, of the Roman composite order, is 75 feet high and 10 feet in diameter, The flutes terminate on the base with palms. A capital, 16 feet square and 12 feet high, surmounts it, bearing on each face a figure of victory, 10 feet high, in antique style, grasping military shields as volutes, the acanthus leaves being wreathed with palms. Upon the abacus stands the cippus, supporting a statue of the hero sculptured in the full-dress uniform of a field marshal, his left hand on his sword, his right arm outstretched, holding a baton. The height of the statue is 17 feet; the total height of the monument is 200 feet. It is almost identical with the Nelson monument in Trafalgar Square, London but is 25 feet higher. The original of both is to be found at Rome, in the column of the Temple of Mars the Avenger.

The Colonne Vendome at Paris, of the same height has a column 3 feet greater in diameter, and the Colonne de Juillet, in the Place de Bas tile at Paris stands 36 feet lower.

An admission of 25 cents is charged for entrance into the monument. There are 235 steps in the stone stairway.

Possibly there is no nobler panorama on the American continent than the superb prospect from the top. In the rear, behind heavy wooding, rises the white cloud formed by the spray from the falls; on the right is the resonant gorge with shaggy and precipitous sides; in front stretches a smiling plain, cut in two by the broad blue waters of the Niagara river, which make a peaceful exit into Lake Ontario. Beyond is the lake, with the curving shores of Hamilton bay on the far left, dimly prolonged as far as the white cliffs of Scarborough, which shuts in the horizon to the north. On the left are the massive locks and great waterway of the Welland canal and the busy factories of Thorold, Merritton and St. Catharines.

The brass tablets in the basement state that beneath the monument are the remains of Major-General Sir Isaac Brock, K. B., (query, K. C. B. ?) and of Lieut.-Col. John McDonell, P. A. D. C, who fell at Queenston on the 13th October, 1812. These have rested in this vault since the 13th October, 1853. Exactly twenty-nine years previously Brock's remains had been interred beneath the original monument some distance to the east, traces of which are still visible. This earlier column was heavier in proportions, the column having a tubular appearance. On the top was a platform, and the whole rested upon a somewhat insignificant pedestal. The militia and Indian warriors who served under Brock, and by whom he was greatly beloved, subscribed most of the funds for its erection. It was blown up in 1840 by a miscreant named Lett, a native of Niagara, N. Y., who crossed from Lewiston with some companions to execute the deed of infamy. This same Lett was generally believed to be the murderer of Captain Ussher. (See Appendix VII). The original burial place of the hero was in the York bastion of Fort George. After the destruction of the first monument his remains were temporarily removed to an adjacent burial ground. Behind the monument, in good preservation, though overgrown with heavy wooding, are the remains of a redoubts and outworks, which formed what was known as Fort Drummond. For a description of the battle of Queenston Heights see Appendix X.

The new suspension bridge, replacing a structure which lasted from 1851 to 1864, will make it possible to return by the opposite side of the gorge. The hill down to Queenston is very steep and stony.

Pedestrians will find steps immediately in front, leading down to the junction with the St. David's road. To visit the obelisk erected by the Prince of Wales in 1860, marking the spot where General Brock fell, it is better to descend a little further, turn to the left and cross the tracks of the electric line. The stone is in a railed enclosure just beside the tracks. Overlooking the obelisk from the east is the shell of a stone building, which often appears in prints and photographs as the first printing house in Canada. The house was certainly occupied by Wm. Lyon Mackenzie[see Appendix XI],but there is reason to believe that he got his printing done at Lewiston, across the river.

Return to the St. Davids road where it joins the other road, and a short ascent will have to be made. Thereafter there is excellent wheeling for two miles and a half. At St. David’s, where are some comfortable, old-fashioned residences, turn south. The wheeling henceforward is particularly good. Over a mile from the village the roadway passes through a tunnel under the Grand Trunk Railway embankment. Here is now a steady ascent for half a mile, which most cyclists will walk. At the summit turn to the left about 400 yards and you come to the gates of what was once the manor-house of Sir Peregrine Maitland, who married a daughter of the Duke of Richmond, and was governor of the province for seven years (1822-9). The original house, a fine mansion, was burned about twenty years after it was built, and its latest successor was also burnt a few years ago. Half a mile off is the quaint village of Stamford. It is said that Sir Peregrine caused certain trees to be cut down which obstructed his view of the parish church from the manor gates. (See Route IV). From Stamford homeward the route is the same as in No. 4.

Route VI.

TO NIAGARA-ON-THE-LAKE.

The first seven miles of this route are the same as in No. V. The village of Queenston, called after the hapless Queen Charlotte, in pre-railroad days was an important distributing centre, and is now the mere skeleton of what it was. Here Lyon Mackenzie edited a paper. (See Appendix 2). A ferry in connection with the Falls electric line crosses frequently to Lewiston. Note the pretty Episcopal church on an eminence above the river, which contains a memorial window. The road to Niagara-on-the-Lake leads due south from the village. The first half mile after leaving the village is broken by an abrupt descent and ascent, where it is better to dismount. Thereafter there is the finest kind of wheeling by a track leading beside the trees on the high river bank. The glimpses of the blue waters of Niagara are refreshing, and the stillness is frequently broken by the splashing paddle-wheels of the red-funneled Toronto steamers which go in and out of Lewiston four times a day. Near Niagara-on-the-Lake the path, now laid with cinders, crosses to the left side of the road. The remains of the earthworks of Fort George will be noticed on the right hand as one comes near the village. The white frame edifice is a Catholic church. Behind it, nestling among the trees, is the fine old church of St. Mark's, the Episcopal place of worship. To the left, at the south-west of the town, the quaint wooden buildings with red brick chimneys are the old quarters of Butler's Rangers, famous in the early history of the settlement. The long Main Street leading down to the beach contains all the stores and two of the smaller hotels. The two largest hotels are two blocks east, on the river front, Golf is played on the common in front of Fort George, and also on the common round Fort Mississauga, at the angle where the river joins the lake. To lovers of the picturesque in scenery the view obtained from the Fort Mississauga common of Fort Niagara at the opposite corner of the river's mouth will be particularly attractive.

About a mile west of Fort Mississauga, on the lake shore, is the large Canadian Chautauqua hotel, with halls, annexes, etc.--a popular resort. At the Queen's Hotel there are excellent tennis courts and a bowling lawn; and yearly tennis and bowling tournaments are held during the summer. Behind the postoffice on Main street is a citizen's bowling green, with facilities for playing by electric light. Two blocks west of Main Street, at its north end, is the old Presbyterian church of St Andrew's. The interior, fitted with pews of a bygone type, boasts a historical 11 three-decker " pulpit of lofty proportions, now no longer in use. In the large stone building which contains the post office, the customs, the town clerk's office, etc., there are the rooms of an active historical society. Here are shown the cocked hat of General Brock, which arrived from England too late for him to wear it, and numerous other relics of interest to the antiquarian. In the rear of the building is a well-selected public library, open thrice a week.

The church of St. Mark's contains a number of interesting tablets. One is to the memory of Colonel Butler, whose name is unfavorably associated in U. S. history with the Wyoming massacre, as it’s called. By his Canadian neighbors he was highly respected and trusted. For an account of the history of this first of Upper Canadian settlements see Appendix 9, " History of Old Niagara." The place is still noted for its excellent black bass fishing. There is a good shelving beach for bathing. A steam ferry boat crosses to Youngstown nominally every half hour, but actually when passengers require it. The road to Virgil leaves the town near the Scotch church of St. Andrew's at the north-west corner, and is excellent for wheeling.

About half a mile of country road brings you to a short declivity. Before arriving at the foot you will notice a gate opening on a path leading through a meadow by a stream that often runs dry. A few hundred yards in, on the further bank among trees, will be found the burial ground of the Butler and Claus families, but originally set apart by Colonel Butler and the early founders of the settlement for the purposes of a public graveyard. Later on, the churchyards of St. Mark's and St. Andrew's took its place. Here it is supposed that Colonel Butler was buried, but there is absolutely no way of identifying his grave. The enclosure is in a discreditable condition. Were it exactly known where he was buried his bones would have been given an honorable re-interment in St. Mark's.

Proceeding to Virgil, turn south on less excellent road to St. Davids. For a description of the remainder of the route see No. 5.

The road to Port Dalhousie leaves the Virgil road on the outskirts of the town, runs north towards the Chautauqua grounds, and then turns west. It is only fairly good. The distance is about 13 miles.

Route VII.

TO ST. CATHARINES AND NEIGHBORHOOD.

Leaving Niagara Falls by Victoria avenue and Fairview cemetery, take the Thorold road a short way to the north of the cemetery and proceed due west. It is a fairly good stone road, with frequent side paths. After riding six miles or so the large swing railway bridge over the Welland canal will loom up. Near its south-east corner stands the Beaverdams monument (see Route 2). Thorold lies to the right. Crossing the new branch of the Welland canal (see Appendix 13), enter the town, which is built on a slope. Merritton is continuous with it. After Merritton is passed leave the high road which branches to the left and take a cinder path (not first-class) to the Homer and St. Catharines road, and on reaching it turn to the left. The town with its 9,000 inhabitants occupies a considerable area. For many years before and after the civil war St. Catharines was a popular health resort, much frequented by Southerners. Certain curative salt waters, which in the past had been popular among the Indians for skin diseases, proved to be efficacious for rheumatism and scrofulous complaints. Two of the houses built to accommodate the invalids who flocked thither have since been turned into educational establishments. At the Welland House these salt baths can still be taken. The river on which the town is situated is the Twelve-Mile Creek, famous in the war of 1812. The road to Port Dalhousie starts from the west side of the town. In leaving for Homer return on the road by which you entered the town, and continue on to Homer, crossing the new branch of the Welland canal. At Homer a road leads off on the left to Virgil and Niagara-on-the-Lake. The road to St. Davids is good wheeling. For the remainder of the journey see Route 5.

Those fond of a long ride may take the tine highway route to Stoney Creek, 284 miles, where Colonel Harvey and a small band of brave men, including Fitzgibbon, surprised and routed a considerable American force, capturing the two generals. See Appendix 12, "The Battle of Stoney Creek."

Route VIII.

TO RIDGEWAY AND FORT ERIE.

Leave Niagara Falls Centre either through the park or by Ferry road and the Loretto Convent. (See Route 1). After passing Chippawa bridge proceed due south for six miles to New Germany and then a short two miles to Stevensville. From Stevensville turn east to the Ridgeway road, and proceed southward on it,

Limestone Ridge is at the intersection of the Garrison road from Fort Erie with this north and south road. It was here that the Fenians who crossed over from Buffalo on the 1st of June, 1866, on their quixotic campaign "for the liberation of Ireland," encamped for the night in a strongly entrenched camp, and were attacked next morning. For the story of the raid see Appendix 5, "The Fenian Raid of 1866." The Garrison road will bring one, after four miles' wheeling, to a road leading to Old Fort Erie, as it is called, a good mile off to the right. The Fort, so famous in the war of 1812, is now a picturesque ruin. Parts of the last wall, where were soldiers' quarters, still remain. The eastern portion facing the river is the oldest part of the Fort, the remaining half having been added during the war of 1812. The south-west bastion, therefore, which blew up as the British were carrying the Fort, and inflicted so severe a loss upon them, was then of very recent construction. The outline of the earthworks is still perfect. A large tree grows from the centre of the wrecked bastion. This explosion took place during a concerted attack which was made on the Fort and the intrenched camp to the north of it by the British and Canadian forces under Gen. Drummond, about three weeks after the battle of Lundy's Lane was fought.

General Brown after his repulse on the 25th of July, retired to Fort Erie, and intrenched himself there. The ground between the Fort and the lake, on the shore of which was a sand hill known as Snake Hill, now nearly obliterated, was converted into an intrenched camp. The British general was camped about two miles off, behind the Garrison Road. On the 15th of August a general attack took place. One attacking party making a detour inland, and approaching through the water, wading, entered the American works, but, being badly supported, turned tail and were driven back in confusion. Things were going well for the British at the south-west corner, when the reserve ammunition in the bastion was fired, some say by an American in a British deserter's cap and tunic. The explosion worked such havoc as to make the attack a failure at this end. On the 17th of September the British batteries, occupying ground to the south of the Fort, were attacked in force by the Americans under cover of a thick fog, and were captured in forty minutes--with considerable loss, it is true, but the sortie was a brilliant one. The batteries were soon after gallantly recaptured. These attacks and sorties were not carried on without a deplorable loss of life, and many brave men of both nations were killed in this small corner of the peninsula. The approach of winter, and the prevalence of sickness in his camp, compelled Gen. Drummond to retire behind the Chippawa River, and General Brown gladly took advantage of his opponent’s retreat to blow up the works at Fort Erie and cross with his whole force to Buffalo, The first man from the British side to enter the deserted fort was Fitzgibbon, always in the foreground. The peace of Ghent, concluded shortly after, happily put an end to hostilities. Those interested in the final operations of the war of 1814 in the Niagara peninsula, will find full details in Major E. Cruikshank's “The Documentary History of the Campaign on the Niagara Frontier in 1814," edited by him for the Lundy's Lane Historical Society. Plans of the Fort, camp and batteries are given.

It is now a favorite picnicking ground of Buffalo excursionists. A short railway runs between the Old Fort and Fort Erie Village, opposite Black Rock--a distance of less than two miles. A steam ferry crosses every twenty minutes to Black Rock.

To return to Niagara Falls, take the shore road, which clings to the river bank all the way. A mile from the village, at a place called Waterloo, it passes under the fine International railway bridge. The road is at first good, so long as it serves the numerous summer and other residences near the village, but it soon turns into an indifferent clay road. At Black, or Frenchman's Creek, seven and a half miles from the bridge, it improves for a mile or two, and then gets worse than ever in approaching Slater's dock, six miles further on. The mile and a half to Chippawa is also rough. For the rest of the way see Route III.

Route IX.

TO INDIAN VILLAGE.

If the upper bridge is crossed to Niagara Falls, N. Y.. then follow Main Street as far as Ontario Street, with asphalt pavement or vitrified brick all the way. This corner is close to the lower or Grand Trunk bridge. Turn east on Ontario Street to the Lockport road, then south on the Lockport road until railway tracks are crossed. Proceed then in an easterly direction, following the broad clay Lockport road with clearly marked bicycle track. After two and a half miles of wheeling the Military road which leads from Cayuga to Lewiston is crossed (Route XI). In the next two miles the railroad is crossed and re-crossed. At a frame cottage on the left turn north for about a mile and then east, passing stone farm houses until, on the left, a low two-storied frame house is reached. Then turn north again into the Indian reservation or village, a short run of a mile and a half. One comes to a crossing where are situated a general store, and opposite it, the schoolhouse. Beyond it, on the way to the River road, is the Council House, and near it stands a Baptist church. Further off is a Presbyterian church.

There is, properly speaking, no village. The 6,000 acres, more or less, which constituted the reservation are parcelled out in allotments, and the 450 Tuscarora Indians live in separate cottages, farming the land. They raise garden and other crops, and the women do fancy work to sell at the booths and bazaars of Niagara Falls, or to peddle it there. The people, though in many cases half-caste, are yet thoroughly Indian in type. The Tuscaroras were one of the famous Six Nations which figure in American history.

Returning, take the road due west past the Council House. At a small school house, about three miles off, the statue of Brock on his monument becomes visible above the trees. Then the turret on the roof of the main building of Niagara University appears on the left. This institution, devoted to the training of R. C. priests, is picturesquely situated above the Niagara gorge, and on the left side of the road, going south. Its handsome chapel was gutted by fire on the 5th of August, 1898. A fine view of the lower gorge and river road is gained from a point immediately beyond the university. Then the Devil's Hole is reached, just half a mile south of the university. For a description of the tragedy which took place here, see Appendix IV, u The Massacre at Devil's Hole." The lofty stone building which looms up in front as one approaches the town is a cold storage house, but was originally built for the purposes of an hotel. The Devil's Hole is exactly two miles south of the lower bridge.

Route X.

TO LEWISTON AND FORT NIAGARA.

Leaving Niagara Falls Centre for the Grand Trunk bridge, cross.it and turning to the left at the first car tracks follow them past the first Whirlpool Rapids and up to the Lewiston Road, by Chasm St. After a mile the road joins another road from the south. This is probably the shorter route back to the town. Passing the Devil's Hole and the Catholic University (see Appendix 4 and Route IX), and the road on the right to the Indian Village, one comes a mile further on the crest of the hill, where a magnificent view spreads out. The wheeling to this point is only fairly good. For three-tenths of a mile the descent is too steep for wheeling. A tall building, once used as an academy but now deserted, will be observed behind the town on the right. Then the Lockport road is reached, which runs to the river as Main Street. Many handsome residences of an antiquated type bear witness to the past importance of Lewiston. The prosperity may partly return if the projected canal for the transporting of the largest vessels between the lakes’ find favor with Congress. So long as goods were carried by land from Lake Ontario to Lake Erie Lewiston remained the headquarters of a powerful firm which had a monopoly of the business. A line of vessels sailed regularly for Oswego and Lower Canada, and brought hither the mail for the whole district to the west. A wooden railway, on runners, worked by means of a windlass, carried the goods up the mountain, the first form of railroad in use in the United States. This trade practically ended with the opening of the Erie Canal on October 26th, 1825. Lewiston was named after a distinguished soldier who was Governor of New York State in 1805-6.

Half way down Main Street the Youngstown electric railway comes in on the right. It follows an inland track mostly through peach orchards. (Fare, 20 cents; wheels are taken on board free). From this point to Youngstown P. O. there is excellent wheeling along the main road by the river. A cinder path, however, that has been laid, doesn't seem to be used, cyclists preferring the packed sand and clay of the roadside. The electric cars come into the attractive village of Youngstown and keep to the main road for a short distance, but leave it a mile before arriving at Fort Niagara.

The garrison, which usually numbers over two hundred, occupy pleasant residences scattered throughout the reservation, a tract occupying 288£ acres in the angle between the lake shore and the river. But for the presence of a few brass cannon, and piles of antique cannon balls, the military aspect of the place is not much in evidence. The fort itself in the extreme corner has a deserted appearance. -There is an earthwork faced with brick on the landward side. If one turns to the right a sally port will be found at its centre, or one can hold on by the river side, and enter the courtyard by the open gateway in the wall facing the river. What is known as the Castle is a quaint building on the north side of the court.

It was at Fort Niagara that the band of adventurers whom La Salle led westward, drove the palisades of a fortification in 1678. Nine years later a more solid fort was erected by Denonville. ln 1757 the "Castle” still remaining, and the "Old French Barracks,” were constructed.

The siege which transferred the Fort to British occupancy began on the 10th of July, 1759. An English army left Albany, and followed the canoe route to Oswego. There they re-embarked and coasted along the south shore of Lake Ontario to Little Bay, five miles to the east. The French and their Indian allies had long been preparing for the attack.

At the beginning of the siege Sir William Prideaux was accidentally killed by the bursting of a bomb, and Sir William Johnson, famous in the annals of the time, and familiar to readers of Stevenson's " Master of Ballantrae," succeeded to the command, with a relative Col. Johnson, as his second. On the 25th of July the place surrendered. Col. Johnson, who fell during the operations, and Sir William Prideaux lie buried somewhere in the fort, but the site of the chapel which held their remains is now unknown.

In the revolutionary troubles Fort Niagara was a Tory or Loyalist centre, but in the treaty of 1783 it was placed within the limits of the republic by the treaty commissioners, owing to the requirements of the boundary line. For thirteen years, pending the fulfilment of treaty obligations by the Republic, the forts were retained by the British government, and occupied by British soldiers. Even when at length an agreement was arrived at that this and other forts should be handed over, there was a delay of several months before properly equipped U. S. troops could be sent to garrison them. The debts due to British creditors from American citizens, the payment of which was expressly stipulated for in the treaty of 1783, were finally settled at six cents on the dollar, after eighteen years of haggling, unworthy of a great nation. It was on the 11th of August, 1796, six years before even this meagre settlement was made, that the British garrison pulled down the Union Jack and left the flag staff to carry the Stars and Stripes.

Before twenty years were over the Union Jack was again to float over the fort). The cruel and unnecessary burning of Newark, now Niagara-on-the-Lake, by General McClure, on the 13th of December, 1813, so embittered the inhabitants and their defenders that immediate retaliation was resolved upon. On the night of the 19th December, a detachment of the crack 100th Regiment, flank companies of the 41st, and a small party of the Royal Artillery, marched down from St. Davids to Longhurst's ravine on the river, whither boats had been brought on sleighs from the lake shore. The muskets of the men were unloaded, to avoid any premature shot; Col. Murray was in command. Landing about two and a half miles above the fort, they proceeded silently along the river bank towards Youngstown. Here they surprised an outlaying company of twenty men and bayoneted them all. The alarm was soon raised, and the picket at the fort fled to secure themselves. The attacking party, swarmed in after them, and in about fifteen minutes the place was in complete possession of the British. With a loss of one killed and five wounded, they had killed sixty-five of the garrison, captured three hundred and fifty, and obtained possession of blankets, clothing, provisions and stands of arms. It was perhaps the most brilliant exploit of the war. At the close of the war the fort was returned to the United States, according to the provisions of the treaty of Ghent.

Youngstown is famous in U. S. annals from its connection with the anti-Masonic crusade. In 1826 a resident of Batavia, N. Y., named William Morgan, published a work in which he betrayed the secrets of Freemasonry. The work raised a storm of indignation among the fraternity. Shortly afterwards Morgan disappeared. The story usually accepted is that he was kidnapped at his home, brought to Fort Niagara, and shut up in a dungeon at the fort with the connivance of the commander, Colonel King, a Freemason. One night three men took him out on the river in a boat and bade him jump. One of the men credited with the deed lived to a good old age in Youngstown, and is remembered by many residents. It is certain that the cause of Freemasonry received a heavy blow in the locality, and that the dark story of his murder was generally credited. The trial at Lockport ended with the acquittal of the accused, Samuel Chubbok and others, but the sheriff of Niagara County was removed from office.

Route XI.

TO LA SALLE AND FORT GRAY.

This gives a pleasant trip of about twenty miles. The first portion of it affords the finest wheeling possible; asphalt, cinder path, shaded by trees, or good macadam. Half a mile out, close to a large factory, will be noticed a single chimney stack, of limestone, all that remains of a French fort, known as Fort de Portage. Upon the same site, Capt. Joseph Schlosser. of the British army, built in 1861, a fort which figures in the history of the war of 1812. A mile beyond this, beside Echota railway station on the N. Y. C. R. R., an island will be noticed close to the river bank. This island comes into the thrilling story of the cutting out of the Caroline paddle-steamer in 1837 by Commander Drew, R. N. (See Appendix XI). Four miles more of wheeling brings you to LaSalle Village. Here one turns east to the bridge, close to which La Salle and Father Hennepin launched, in 1679, the first European vessel to navigate these waters. The Griffon, which was of 60 tons burden, after a varied life, perished a few years afterwards in Lake Michigan. La Salle's company consisted of about sixty sailors, boatmen, hunters and soldiers, On this expedition he proceeded to exploit the great lakes, attempting to colonize their shores, and descending the Illinois river, reached the Mississippi, and by it the Gulf of Mexico. He it was who named the district at its mouth Louisiana. Five years after this eventful journey he was murdered on the banks of the Trinity river in Texas, March, 1687, at the age of 44. Born a plebeian at Rouen, France, in 1643, Rene Robert Cavelier was educated as a Jesuit priest, and renounced the church for a commercial life. At the age of 23 he left for Canada, and twelve years later, on account of eminent services as an administrator and explorer, was ennobled and became the Sieur de LaSalle.

The Military road leading in a straight line to Lewiston Heights, meets the Buffalo road from the Falls at the bridge over Cayuga Creek. In good weather it will give a nice spin of seven miles and a half to Fort Gray, one of a chain of forts which at the beginning of the century guarded the frontier from Niagara to Buffalo. For the rest of the way back, see Route IX, "To Indian Village."

Route XII.

TO BUFFALO AND BACK.

For the first six miles of the route to Buffalo, see Route Al. Instead of turning to the left at the Cayuga Creek for Lewiston Heights, cross it and rejoin the electric railway tracks. About three miles of good wheeling brings one to Edgewater pier on the mainland, answering to Edgewater on Grand Island, a favorite resort for yachting and aquatic sports. At this point the electric line turns inland over a viaduct. Proceed by cinder path (somewhat treacherous from vitreous slag) and dusty highway into Tonawanda. At the many-tracked railway station proceed by the inner of the two broad streets which meet here, and cross two bridges. The electric line crosses these, but on reaching the further side turns off sharply shoreward. Take Delaware Avenue to front, a fine street paved with red vitrified brick, changing to white brick a mile or two further on. The red brick tower of a handsome armory will be observed on the left soon after entering the avenue --a good landmark. After four miles and a half of vitrified brick the pavement changes to asphalt. Two miles of this and the roadway passes under a railway embankment and then crosses the Scajaquada Creek at Forest Lawn Cemetery. To the right will be noticed the handsome towers of the State Insane Asylum. One block from this bridge the road turns sharply to the left. It then goes straight down into the city, and one can turn into Main Street anywhere between North Street and Chippawa Street. From Chippawa Street to Exchange Street on Main Street is the busiest part of the city, the bicycle stores being near the crossing of Genesee, north and south. Six blocks south of Genesee is Ellicott Square, the largest office building in the world, containing 600 offices and 40 stores, named after the pioneer settler of Buffalo, Joseph Ellicott. With its 300 miles of asphalt pavement, Buffalo presents wonderful attractions to wheelmen. It has a fine park system. There are over a dozen parks in all, with a total area of nearly one thousand acres. Near Forest Lawn Cemetery, on the north-west, beginning at 2100 Main Street, is the Park, with zoological garden and lake. Then there is the Front Park, on the river, near Fort Porter, the home of the fighting 13th Regiment, U.S. infantry, noted in the war of 1812 and in the late war. Here the band of the regiment frequently plays in the evenings. To get to it turn west from Main Street on Chippawa Street seven blocks, one block on Georgia Street, then run north-west on Prospect Avenue to Porter Avenue; turn down to the left two blocks. Humboldt Park, formerly The Parade, is reached by turning east on Best Avenue at 1109 Main Street, or by following Genesee Street eastward until it joins Best Street. Cazenovia Park, on Cazenovia Creek in the south-east corner of the city, is reached by Seneca Avenue, with asphalt pavement from the Erie railroad station. It has a botanical garden, and is also noted for the Red Jacket Monument, erected by the Buffalo Historical Society to the memory of the famous chief of the Seneca Nation. The lndian name of this orator and warrior was Sagoyewatha, the other being a soubriquet because of a handsome red coat he received from Sir William Johnson. He was born in 1751, was active on the British side at the time of the revolution; later in 1810 opposed Tecumseh, and in the war of 1812 was of service to the U. S. armies. He survived till 1830, but was given over to intemperance in his later years. The district is associated intimately with the Seneca tribe of Indians, who had a settlement within the bounds of the present city on the south. Tonawanda was a former place of assembly for the Indian tribes of the vicinity.