"Art Solomon's Hopeful Realism"

- Full Text

- Art Solomon's hopeful realismI cannot bring myself to believe | That God intended for any of His children | To be Locked in iron cages | Behind stone walls | Or shot and killed in cold blood by prison guards | Or police.

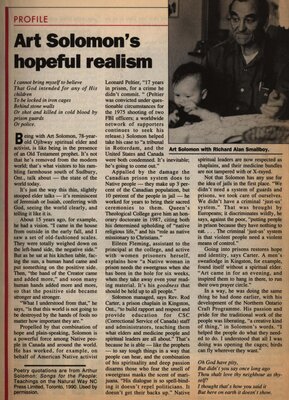

Being with Art Solomon, 78-year-old Ojibway spiritual elder and activist, is like being in the presence of an Old Testament prophet. It's not that he's removed from the modern world; that's what visitors to his rambling farmhouse south of Sudbury, Ont., talk about - the state of the world today.It's just the way this thin, slightly stooped elder talks - it's a reminiscent of Jeremiah or Isaiah, conferring with God, seeing the world clearly, and telling it like it is.

About 15 years ago, for example, he had a vision. "I came in the house from outside in the early fall, and I saw a set of old-fashioned scales. They were totally weighed down on the left-hand side, the negative side." But as he sat at his kitchen table, facing the sun, a human hand came and put something on the positive side. Then, "the hand of the Creator came and added more," and soon many human hands added more and more, so that the positive side became stronger and stronger.

"What I understood from that," he says, "is that the world is not going to be destroyed by the hands of fools no matter how important they are."

Propelled by that combination of hope and plain-speaking, Solomon is a powerful force among Native people in Canada and around the world. He has worked, for example, on behalf of American Native activist Leonard Peltier, "17 years in prison, for a crime he didn't commit." (Peltier was convicted under questionable circumstances for the 1975 shooting of two FBI officers; a worldwide network of supporters continues to seek his release.) Solomon helped take his case to "a tribunal in Rotterdam, and the United States and Canada were both condemned. It's inevitable; he's going to come out."

Appalled by the damage the Canadian prison system does to Native people - they make up 3 percent of the Canadian population, but 10 percent of the people in jail - he worked for years to bring their sacred ceremonies to them. Queen's Theological College gave him an honorary doctorate in 1987, citing both his determined upholding of "native religious life," and his "role as native missionary to Christians."

Eileen Fleming, assistant to the principal at the college, and active with women prisoners herself, explains how "a Native woman in prison needs the sweetgrass when she has been in the hole for six weeks, when they take away even your reading material. It's his goodness that should be held up to all people."

Solomon managed, says Rev. Rod Carter, a prison chaplain in Kingston, Ont., "to build rapport and respect and provide education for CSC (Correctional Services of Canada) staff and administrators, teaching them what elders and medicine people and spiritual leaders are all about." That's because he is able - like the prophets - to say tough things in a way that people can hear, and the combination of his spirituality and deep passion disarms those who fear the smell of sweetgrass masks the scent of marijuana. "His dialogue is so spell-binding it doesn't repel politicians. It doesn't get their backs up." Native spiritual leaders are now respected as chaplains, and their medicine bundles are not tampered with or X-rayed.

Not that Solomon has any use for the idea of jails in the first place. "We didn't need a system of guards and prisons, we took care of ourselves. We didn't have a criminal 'just-us' system." That was brought by Europeans; it discriminates wildly, he says, against the poor, "putting people in prison because they have nothing to eat... The criminal 'just-us' system is that violent people need a violent means of control."

Going into prisons restores hope and identity, says Carter. A men's sweatlodge in Kingston, for example, found itself without a spiritual elder. "Art came in for an evening, and inspired them to hang in there, to run their own prayer circle."

In a way, he was doing the same thing he had done earlier, with his development of the Northern Ontario Craft Programme. His passion and pride for the traditional work of the people was liberating, "a creative kind of thing," in Solomon's words. "I helped the people do what they needed to do. I understood that all I was doing was opening the cages; birds can fly wherever they want."

Oh God have pity, | But didn't you say once long ago | Thou shalt love thy neighbour as they-self? | I thought that's how you said it | But here on earth it doesn't show.

Sitting in the Solomon's kitchen, you get glimpses of the importance of this elder with the long black braid. The large, warm room is full of people: a Native law student and his wife who have driven far out of their way to get here; their small son, who toddles across the floor in pursuit of a large dog; Eva Solomon, preparing a massive lunch on the big black wood stove.Talk flows freely around the table - apartheid, religion, the prison system, the future - while Solomon provides his blend of blunt realism leavened with hope. The world as we know it is disintegrating. After Oka, "we have to re-establish our sovereignty as a people. Nature abhors a vacuum. As one nation is coming apart, we have to step in and fill its place."

That means accepting the idea of Native self-government. "Mulroney said, 'We would think about establishing Native self-government.' They have no power to do that. We have to assert our own self-government. Ourselves. And we have to do it individually, by taking charge of our own lives."

Solomon has little patience for leaders who say one thing and do another. "Mulroney has been bragging about trying to aid to human rights. But look at the Innu, the Lubicon, what's happening in Barriere Lake (Que.), James Bay. For over 50 years the people at Lubicon Lake (Alta.) have been looking for some rights, and both governments have been playing with them."

Again, the prophet emerges, blunt, outspoken, fuelled by a vision. "Our destiny and the destiny of our children is not negotiable with any government. We are dealing with criminal captive state governments - captive in the sense they are dancing to the music of the corporate agenda. They are totally corrupt and on the side of the corporations. They're all about making it safe for money."

It's not a cheerful vision for any of us whose lives are built around profit. "But they are going to lose it. When that happens we are going to look at each other as human beings and say who is sister and who is brother. That is all that is going to matter. Falsehood won't work any more."

It distresses me no end that so many pray to God | And ask Him-Her to do this and do that, but seem not to | Understand that our part is to be God's hands and feet | And voice.Outside, the snow falls. Eva stirs potato soup and slices ham; the toddler makes himself at home on Art's lap, and talk turns to religion. Solomon has long dissociated himself from his Roman Catholic upbringing in Killarney, Ont. "I'm a born-again pagan," he chuckles. But the international body for which he has the most respect is the World Council of Churches - "the most legitimate body I know," he says. His work with the WCC and the World Conference for Religion and Peace has taken him to Geneva and Nairobi, China and Mauritius.

Carter describes his attendance at an All Native Circle Conference (ANCC) gathering in British Columbia three years ago. "He talked about men and women in prison, and prison as blasphemy. The room was electric. His physical health was not good, but he had travelled all that way to speak with us. The elders were hanging onto every word. His richness was so evident, his passion against the prisons we have constructed so evident, yet his underlying spirituality so evident."

The woman is the foundation on which nations are built | She is the heart of her nation... | The woman is the centre of everything.Eva calls everyone to lunch. Talk slides smoothly into the dining room, past walls filled with offerings from their 26 grandchildren.

Art glances at Eva and talks about women. This is where he finds hope for the world. At a meeting in Fredericton, of the Native Women's Association of Canada, he was sitting on a woodpile, listening to a woman "teaching other women to affirm each other instead of ripping them apart." He was moved further along a line of thought he had been pursuing for a while. "It is time for women to pick up their medicine and heal the sick and troubled world. I have noticed women have been the driving power in making things better. Women have more power than men have, because it was given to them. That's one of our teachings."

At the same ANCC gathering in which he had mesmerized the elders, he challenged the women to pick up their medicine. "What is our medicine?" a young woman asked. Typically, Solomon took his time replying. "I had to think about it all that winter. And the only conclusion I could come to is that the woman is the medicine."

He pauses, reaches for a way to explain this crucial concept. "You look at a baby nursing, contented; that is the medicine in action. The woman has love in abundance for her children. That is one of the ways they manifest their power."

Laurel Claus-Johnson, a Queen's University student who is frequently Solomon's host when he visits federal institutions in Kingston, says that "if a Native man is traditional, he has been taught about the power of women, and most likely encouraged to live that out. But Art is naming women's power, and as he names it, he attempts to live it, and that is the teaching process he gives back to women - and then again, to men too."

Not all elders are willing to grant women the power he does. The drive for equal recognition that has "endeared him to the female inmates also puts him in a precarious position in his own culture, a position he is willing to carry," says Carter. "There are still pockets of male chauvinism in the Native community." For all Native women - not only those in prison - that position is crucial. Claus-Johnson says that "in our journey back to spiritual rebirth, there is a lot of unanswered questions in our minds. To have this man name things that are important to his own spiritual journey, it is then much easier for us to make the connections."

There is nothing more to say except | That good will triumph over evil.Solomon comes quietly outside to say goodbye, padding around on the snow in blue knit slippers with small fur pom-poms. His accomplishments sit lightly on him. He has been a director of the Union of Ontario Indians; a founding member of the World Crafts Council and a spiritual elder in the American Indian Movement; he was instrumental in founding Newbery House, a halfway house for Native people who have been in prison; he has received Ontario's Order of Merit, received a Doctor of Divinity from Queen's University, and a Doctor of Civil Laws from Laurentian University.

Honor sometimes softens prophets. Not this one. He continues to be, in Carter's words, "affirming in his radicalism, and yet persistent." And he continues to make connections, not only between men and women, but between Native and Christian. "I recognize there are good people in all those faith traditions. We all have the same Creator anyway. There is only one sun in the sky. And there is only one Creator. Our responsibility as Native people is to teach the people how to live in harmony with the Creator, which means men and women living in harmony with each other."

- Media Type

- Newspaper

- Publication

- Item Types

- Articles

- Clippings

- Description

- Being with Art Solomon 78-year-old Obibway spiritual elder and activist, is like being in the presence of an Old Testament prophet. It's not that he's removed from the modern world; that's what visitors to his rambling farmhouse south of Sudbury, Ont., talk about- the state of the world today."

- Date of Publication

- 1993

- Subject(s)

- Personal Name(s)

- Peltier, Leonard ; Solomon, Art ; Fleming, Eileen ; Carter, Rod.

- Corporate Name(s)

- Correctional Service of Canada.

- Local identifier

- SNPL003521v00d

- Collection

- Scrapbook #5

- Language of Item

- English

- Creative Commons licence

[more details]

[more details]- Copyright Statement

- Public domain: Copyright has expired according to Canadian law. No restrictions on use.

- Copyright Date

- 1993

- Contact

- Six Nations Public LibraryEmail:info@snpl.ca

Website:

Agency street/mail address:1679 Chiefswood Rd

PO Box 149

Ohsweken, ON N0A 1M0

519-445-2954