Harry Barrett is pure Oakville, always has been. From the day he was born in 1925 in an upstairs bedroom is his parents’ house on Trafalgar Road, he was destined to be part of Oakville history.

A plumber by trade, he was the 42nd Mayor of the Town, serving for 12 years, from 1973 until 1985, “never losing an election,” he likes to say.

A soft-spoken guy, but not shy, he once claimed, “The reason I did so well at politics is because I was never a politician.”

Now that’s a paradox, but by all accounts, Barrett was a practical guy, who looked for sensible solutions, just the way you might expect a plumber running a small business to do.

Barrett, measuring about five feet, six inches was mayor about the same time as another “tiny, perfect” mayor, David Crombie. Crombie was top dog at City Hall in Toronto from 1972 until 1978 at which time he moved on to federal politics. In 1988, Crombie led a Royal commission on the Lake Ontario Waterfront and stayed on to lead the charge for Waterfront Regeneration in Toronto and the Waterfront Trail that currently stretched from Brockville to Niagra-on-the-Lake. While Crombie has carried the ball a fair distance, it was Barrett who started the ball rolling to claim the Waterfront in Ontario.

Barrett had served five years on Oakville Town Council before winning the mayoralty and 15 years before that on the local Planning Board. It was while on the Planning Board that he discovered a clause in the Planning Act that entitled the municipality to retain five per cent of land for public use.

Barrett explained: “The Township was in the habit of taking whatever the developers offered or even cash in lieu of parkland. I said that was crazy! Why don’t we take the waterfront? Which we started to do and it became policy to acquire that land for public use, 50 feet from the top of the bank.”

Of course, this was not accomplished in isolation. The former mayor acknowledged that while he brought the idea to the table, it took a sympathetic mayor at the time, Mack Anderson, and councilors with foresight, one of which was a newly galvanized Bill Cudmore, to actively get behind the policy.

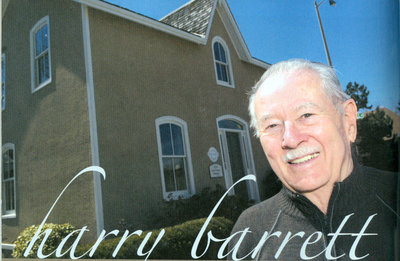

As previously noted, Harry - actually Bertram Henry Barrett - was born in 1925 in a house at 140 Trafalgar Rd., originally an inn and currently the offices of investment advisor, John Hobbes. For a number of years the house was home to The Added Touch, a well-known mail order and retail business.

Barrett had one brother, Jack, eight years his senior, now a retired military officer living in England. His parents were George Barrett and Mary Toms. The Barretts hailed from Cornwall, England, and a long line of seafaring men, but George, Harry's dad, elected to apprentice as a plumber instead. He came to Canada to start a business in Oakville around 1907, joining forces initially with McGregor's Hardware then located on the main street (in what is now the Prime Time Sports Bar). The main street, now Lakeshore Road, was then called Colborne Street. The early part of the 20th century was a good time to be a plumber in Oakville and Trafalgar Township. The town was building water mains and sewers for the residents and the big estates on the waterfront were being carved out by wealthy Toronto families like the Coxes, the Ryries, and the Eatons. To the west of Bronte Village, the Cudmore's new house on the lake road needed a first rate plumber and Barrett's got the call. Barrett's Plumbing & Heating found a ready market and prospered until the Stock Market Crash of 1929 and the Great Depression knocked the wind out of pretty well everyone's sails.

"We ate a lot of turnips in those days," Barrett quipped. Times were lean until after the war when business picked up again.

The Barrett home on Trafalgar Road at Randall Street, built originally in 1834, was solid post and beam construction and served as both home and workshop for a time. There was a yard with chickens and rabbits running around and a small barn on the property. Next door, Harry's maternal grandparents, the Toms, lived along with his aunt. The Gilbrae Dairy was just a stone's throwaway on Church Street with a small stable in back for the delivery horses.

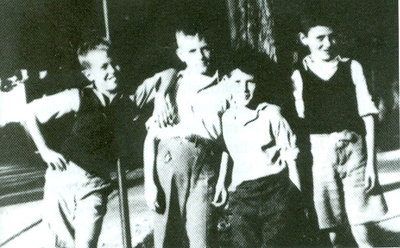

The boys would play shinny on Randall Street, and in the summers, swim in the creek. Sometimes, young Harry and his buddy Bill Russell went out to the lake at Coronation Park where a small cottage community was established. He and his brother and father also built model sailing ships and raced them at the CNE and in Toronto Harbour.

At one point in his childhood, Barrett had another convergence with history. The famous Canadian schooner, Bluenose, was sailing up the Great Lakes to the Chicago World's Fair in 1933 and made a stop in Toronto. Barrett was only eight years old.

"Somehow my father had made the acquaintance of Captain Walters, I don't know how, but anyway we went out for a sail and as we went through the eastern gap of Toronto harbour, the skipper said, 'George, give the boy the wheel.' My dad was just about having a fit watching me at the wheel so the captain said, 'Don't worry about it, George, she sails herself.' And so she did."

Furthermore, Barrett said, Captain Walters gave his dad a set of drawings for the original Bluenose, a possession that he inherited and treasures to this day.

But it was not all sports and games for the children of Oakville; Barrett went to Brantwood School on Allan Street, then Central School which was then on Navy Street, and finally to Oakville High School on Reynolds Street. Then at the age of 18 with the war still raging in Europe he joined the "school of hard knocks," serving in a reconnaissance unit of the 4th Field Artillery Regiment in the Royal Canadian Army.

Barrett pointed out that Oakville had the highest percentage of military reserves in Canada and also the highest percentage of casualties. Thankfully, he came home after the war and joined his father in the business. In 1951 he married Jacquie, who lived up the street. She was a chemist with the British American Oil Company at the time and they proceeded to have a family, two daughters, Caroline and Laurie. After their first daughter was born in the early 1950s, the family looked around for a house of their own.

"We looked for an older house close to the schools in central Oakville, but even then you had to spend a fortune to get anything decent," he recalled. "Fifty years ago, when we were looking, nobody wanted to buy anything south of Robinson Street. Places were cheap, but they were old and rundown; the waterfront was smelly with algae and dead fish. Now it's a heritage district and the most expensive part of town.

"We decided to buy a lot, a third of an acre, just east of town, on some property owned by a chap I went to school with, Hugh Peckett. There was nothing around. It was kind of swampy with wild strawberries and asparagus. Still we paid $4,200 which was a lot of money back then."

The house, Jacquie and he designed themselves, was a bungalow, about 1,400 square feet, small by today's standards, and it cost another $16,000 to build. Barrett lives there still. The property has held its value remarkably well. He also owns the workshop and apartment built in 1946 on Randall Street beside his old family home. His late wife Jacquie ran a small antiques business, Morwenna, in a storefront there.

"Every Canadian dreams of owning a piece of land," he would comment with just a hint of annoyance. "I don't know how you can do that in a condominium."

Barrett maintains that his greatest contribution to the town, apart from fiscal responsibility, was in reclaiming the waterfront and improving the harbours as recreational places.

“I made only one promise as mayor,” he related, “I was going to redevelop the waterfront.

The two harbours, he said, were described in the press of the day as “the harbours of neglect.” It was clear there was work to be done. In 1973 he installed the Harbours Development Authority and hired the capable Gurth Bramall as Harbourmaster.

“Council let me pretty well appoint people that I knew could do the job,” the former mayor related. “I called it an authority, not a committee, because I’m a firm believer that unless you give people some authority they really don’t take an interest.”

The volunteers appointed to the authority were guys like Bob Jones and Bill Cudmore, who along with town staff, had a mandate to acquire lands around the harbours, clean-up debris, landscape, dredge and create new moorings. The harbours were to be improved in parallel with the central goal of creating a pleasant, accessible facility for boaters and the general public.

When the late Gurth Bramall retired around 1993, the harbours were both in great shape, self-sustaining financially, and he had nothing but praise for Barrett. Today at the age of 82, Barrett is still active as chair of Heritage Oakville and advisor to the Oakville Historical Society. For 30 years he was on the board of Directors of the Oakville Humane Society. Now he travels frequently with his daughters and sons-in-law, returning home with tales from the Orient Express, for example, or Harry’s Bar in Venice. He delights in the progress of his two grandsons.

Barrett represents a rare few who were born, ran a local business, went to war, ran for office and raised a family in this town. He brings a long and involved perspective.

“I was a businessman. I have no sympathy for municipalities that go crying to the Feds and the Province for more money. Simply put, you’ve got to live within your means. My employees drove better cars than I did half of the time, but that was fine. That was how it was.”

Would he want to be a Mayor of Oakville today? “No thanks,” he said without hesitation. “Been there, got the t-shirt. I was pleased to serve. I enjoyed what I did. I never did anything in my life that I didn’t enjoy. In the end I thought it was time to move over and let somebody else have a turn.”

Politician or plumber, one think is for sure, he’s pure Oakville.

By Karen Alton

Taken from “Oakville’s 150th” (2007), courtesy of The Oakville Beaver