Growing up on the other side of town

Romance writer Mazo de la Roche once described Oakville as "sedate, respectable, and very different from the rowdy, good-humoured poverty of Bronte,"

She made the colourful comparison in her first novel, Possession, based largely on her four-year stay at the old Crabb farm (formerly the Charles Sovereign House) just west of Bronte. She lived there from 1911 until 1915. The book, published in 1923, has many descriptive references which make the setting unmistakable, though in fact the place names were recorded as Brancepeth (for Oakville) and Mistwell (for Bronte). The real life Cudmore family became the fictional Chards: the wealthy Mr, Jerrold was based on Major Osler, a gentleman farmer who also lived in the neighbourhood.

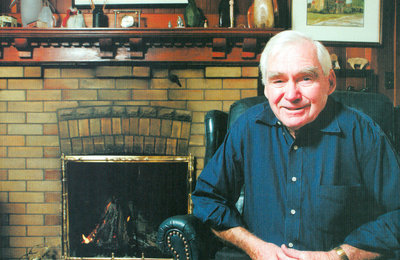

There's been a lot of water under the bridge since then and many changes to both Bronte and Oakville, but Bill Cudmore says the novelist got a lot right, especially the part about "poverty." However, he would say it was more of a dark humour that got folks through the rugged times and "there was no romance whatsoever" in the hardships that many of Bronte's early residents endured.

Cudmore is 75 and has lived his life in Bronte, from boy to man, in the impressive 14-room house on Lakeshore Road on the edge of Cudmore's Garden Centre. His father, Ernest Jackson Cudmore, known to all as "Mike," built the big house around 1920, moving the family up from the original Cudmore farmhouse near the lake.

It was while still living in that lake house that Mike and his seven brothers and sisters represented the "tow-headed" Chard children, who lived next door and poked their heads through the fence where Mazo de la Roche wrote stories to sell to magazines. Bronte was apparently fertile ground for a literary treatment.

In any case, while he enjoyed the descriptive passages in Possession, Cudmore is fairly disdainful of any romantic notions attached to the past.

As a farmer's son and the father of four, himself, he worked the land most of his life on the family farm. Even as a boy he had chores, like cutting asparagus before school and milking the cows after school. But one summer as a teenager, he signed onto the Bronte fish boat of Jack Osborne. He says it gave him some insights. They are unequivocal.

"Fishing was a dirty, cold, hard, miserable, mean way to make a living," he said, "nothing nice about it. The glamour and romance of what a marvelous place old Bronte was is pure fiction."

There are stories out there, he said, designed for the Ladies Aide Society. "The real stories are lost forever."

"Bronte, as I remember it, was a working class village, where the object of most people was to have a job tomorrow - clean some nets, paint a house, or maybe get a job at the basket factory for a week. It was looked on by Oakville as a low class area," Bill recalled.

"When I started high school (then on Reynolds Street in Oakville), my dad and mum were a bit worried. They told me to stay with the other Bronte kids because they were afraid I might get beaten up." Their worries turned out to be misplaced. "Some of my best friends today are Oakville guys I met at high school."

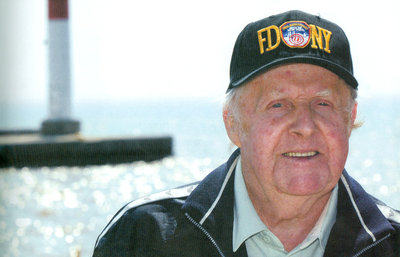

Ken Pollock, also a lifelong Brontian, knows first hand how cruel the lake can be. The Pollocks, Ken's father and uncles, were fishermen and mariners to the bone, "up before dawn and out on the lake, winter and summer, just to make ends meet."

Most of the fishing boats were gone from Bronte Harbour, however, by the time he reached manhood in the 1950s. He became a firefighter for 40 years, having volunteered at the age of 14.

The seventy-something gent recalled a story from his childhood when his Uncle Byron was lost for three days on the lake in his small fishing boat. Pollock was only five or six at the time. It was February 1935. Byron had two crew mates with him, Skin MacDonald and Mike Joyce.

"I still remember sitting on my mother's lap on the veranda of Glendella," Pollock related, "looking out at the lake and waiting. The fishermen went out on a Friday morning and didn't come home Friday night. People drifted down to the lake wondering where they were. Men on the shore were yelling and they actually heard the guys in the boat talking, but there was heavy ice all along the shore and thick fog. The voices drifted away. They fired shots in the air."

According to Pollock, the next morning an airplane came from Toronto to join the search, to no avail. Nothing. Then an ice- breaker tug came to help but couldn't find the fishermen either.

"On the third day a fish boat from Bronte - Bill Bray's boat - went out because Bray figured they knew the ice and the lake. They found them alright, after a few hours, and towed them in, half froze, and hungry as bears. My uncle said they could have eaten the leather out of their shoes."

Life in Bronte

Pollock was born in a house at 119 Jones St., a house his dad John Pollock built. He says his ancestors came to Bronte in 1849 and once owned land right on the lakefront stretching from the east pier to Nelson St. Unfortunately, much of that land south of Ontario St. simply disappeared, eroded by the lake over time and Pollock thinks the deeds were returned to the township. Now the Outer Harbour construction has reclaimed a good portion of land in that area for parkland and created many new slips for recreational craft.

Pollock says the last fishing boats left in Bronte were in the early 1950s - the very last being Freeman Bray's boat - though the fish had been dwindling since the war. He blames the development of detergents flushed into the lake, the influx of lamprey eels and the test-firing of guns on Hamilton beach, which disrupted the spawning beds of the lake trout.

"What drives me wild," he lamented, "is that the old fish shanties, and all the reels where they dried the nets and so on, they could have kept those and made them something really picturesque like in Newfoundland and Nova Scotia."

"The Americans used to come here in the summer, you know, by the hundreds to paint the harbour scenes, but we didn't appreciate it then."

"The shanties deteriorated and had to be torn down, everything disappeared."

Pollock is wistful about early Bronte history. He is working on his own book about old Bronte with pictures and many stories about buildings now gone and the people who animated the place.

"Things I want my own children to know," he said.

For his part Meredith "Mack" McKim, now 78, has happy memories of the Bronte of his youth. He has lived here for many years, off and on. Born in western Canada, his first memory of Bronte is as a nine-year-old boy with him mum, recently widowed, and his two younger siblings, Ralph and Noelle.

"When mother brought us here for a day at the beach," he recalled, "my first impressions were of a small place, but beautiful. We loved the beach, it was like a resort. She asked us if we wanted to live in Bronte and of course we said yes!"

The family moved into a white house on a one acre lot on Bronte Road just south of Rebecca Street in 1938. The house is still standing, and little changed, according to McKim. His mother later built a house on River's Bend Lane where Mededith and his wife, Yvonne, now reside looking out on the marshy banks of the Twelve Mile Creek (Bronte Creek). In an old class photograph he pointed out many of his school mates from the Bronte public school where there were only two classrooms in use at the time and two teachers, Mr. Hopkins and Miss Montjoy. That made for quite a range of ages. Both his brother and sister were in class, along with Buster MacDonald, Ruth Abels - the daughter of a Czech doctor who came as a refugee during the war - Ken Pollock, Bill Cudmore, Mucker MacDonald - "don't know why they called him Mucker" - Doris Highfield, "her father Sam ran the mushroom house up by the railway."

Lois Bray was there, and her two sisters. And Bunny Ore - "her dad Jack Ore was a farmer on Radial Road (Rebecca Street). I drove tractors for him.

At the age of 13, Meredith was invited by Freeman Bray to join the volunteer fire department. Bray was on his paper delivery route. The war was on and men were in short supply on the home front.

"I was assigned coveralls and given the job of maintaining the siren," Mack grinned. "This was big time for me: this was my contribution to the war effort."

McKim would later become a Cub Pack leader before he was married, as well as take an active role in the local Teen Town group that met at the Bronte Community Club (formerly the Orange Lodge) located on the south side of Lakeshore Road, between Bronte Road and the village dump (later the site of Bronte Yacht Club).

He has one over-reaching claim to fame in Bronte. McKim was the driving force behind the diving tower on the west pier. He explained, "When the west pier was reconstructed shortly after the war there were hopes of putting in a diving tower. The devices to hold the structure were implanted at that time, about half way out on the concrete portion at a point where the water on the west side of the pier was deep enough to dive."

According to a Globe & Mail caption in the summer of 1948: "The drive to buy the board was organized by 19-year-old Meredith McKim. He also got Dominion Government permission to put a board on the pier and arranged for insurance and proper life saving arrangements. Finally, he built the board himself."

"I think Teen Town bought the insurance which was $50 a year," McKim recalled. "But nothing bad ever happened that I know of. Nobody would have made a claim in those days anyway. The board was there for years, but it wasn't maintained the way it should have been. Finally, the ice knocked it down."

"The diving tower became a focal point for our swimming," he continued. "In those days, the water was quite clear in the lake. Before the tower, the swimming was mostly between the piers, in the creek water, which was warmer, but it was also brown."

These are just a few selected thoughts of three long-time Bronte residents, the tip of the iceberg. There is plenty more where this came from. It is surely a worthwhile exercise to look back from time to time and be reminded of just how we got from there to here and perhaps marvel at the fortitude and ingenuity of our forefathers.

Be warned, however, whether it is a novelist like the late Mazo de la Roche, or a living story teller like Bill Cudmore, Ken Pollock or Meredith McKim, truth and fiction often walk hand in hand, and memory is a slippery slope.

By Karen Alton

from "Oakville's 150th", courtesy of the Oakville Beaver