Nikolai Bokan: a Biographical Essay

The Bokan Family

Panels

IntroductionThe Criminal Case FileThe TrialThe Bokan FamilyNikolai Bokan's Life Pre-FamineFamine (1932-33)TolstoyanismPhotographyLinks

View the "Nikolai Bokan Collection"Most of the biographical information included in this directory was retrieved from the writings and materials created by Nikolai Bokan, and the story of the Bokan family as outlined here is therefore told primarily from Nikolai’s perspective. Soviet documents related to the trial of Nikolai and Boris were also referenced, as well as the few materials in the case file that offer insights into the perspectives of other family members, including interrogation reports with Boris, Lev-Leonid, and Anna Bokan, and correspondence between Nikolai and his children. Any contradictions between the narratives have been noted.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

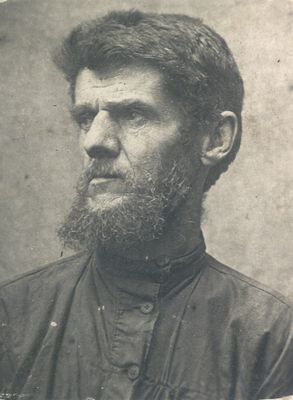

Portrait of Nikolai Bokan Details

Nikolai Bokan: Nikolai (Mykola) Fedorovich Bokan (1881–1942) was a photographer from Baturyn, Chernihiv oblast, in Soviet Ukraine. Among Nikolai’s surviving photos are those that document his family’s experience of the Holodomor, and notably the death of his son Konstantin from starvation. Nikolai’s photos offer a uniquely personal perspective on the experience of famine and speak to the famine’s devastating impact on family dynamics amid broader social and political transformations. As Nikolai was a devoted member of the Tolstoyan movement, which was based on the religious and political writings of Leo Tolstoy, his writings and photos also provide insight into the fate of religious groups amid Soviet-era repressions. Although the official trial document identified Nikolai’s nationality as Ukrainian, he personally did not associate himself with any national community which was prompted by his vision of anarchist ideas.

In the fall of 1937, Nikolai Bokan, along with his son Boris Bokan were arrested and charged with anti-Soviet propaganda and agitation. In 1938, they were sentenced to hard labour in the Far East. Nikolai was sentenced to eight years of hard labour in Yagrinlag, where he died in 1942.

In the fall of 1937, Nikolai Bokan, along with his son Boris Bokan were arrested and charged with anti-Soviet propaganda and agitation. In 1938, they were sentenced to hard labour in the Far East. Nikolai was sentenced to eight years of hard labour in Yagrinlag, where he died in 1942.

Portrait of Vasilina Bokan Details

Vasilina Bokan: Vasilina married Nikolai Bokan in 1905. It is unknown when or how they met, although she is presumed to have been a local of Baturyn or the surrounding regions. Vasilina and Nikolai had seven children born between 1906 and 1919. Little is mentioned about Vasilina in Nikolai’s writings. In his memoir, Nikolai accuses his wife of having a negative influence on their children owing to her supposed “non-religious” attitude. Though Vasilina was a Christian, Bokan believed that she blindly followed religious tradition and the teachings of a corrupt clergy without attempting to attain religious or spiritual enlightenment.

Portrait of Nikolai (Jr.) Bokan Details

Nikolai Bokan (Jr.): Nikolai was the eldest child of Nikolai and Vasilina, born in 1906. He was the only child in the family to have received some formal education from a tutor before Nikolai (Sr.) began homeschooling his children, owing to his opposition to the anti-religious state curriculum. After shirking his father’s efforts to engage him in photography, Nikolai (Jr.) enrolled in a secretarial course and took a position in the local village administration. According to Nikolai (Sr.), he was caught embezzling public funds on more than one occasion. Though his initial misdeeds prompted a mere reassignment to neighboring villages, he was eventually tried and sentenced to five years of imprisonment. Nikolai (Sr.) blamed the authorities for encouraging his son’s recidivism. After his release, he became a farm labourer in Tavriia. At the start of the famine, Nikolai (Jr.) was the only Bokan child no longer living in the family home. In 1934, Nikolai (Sr.) wrote that it was unknown whether his son was at that time alive.

Portrait of Vladimir Bokan Details

Vladimir Bokan: Vladimir Bokan was born in 1908. As a child, he suffered a serious injury to his eye. According to Nikolai, Vladimir was denied proper treatment from local medical authorities. The reasons for this refusal are unclear. Vladimir would continue to excuse himself from work on account of his partial impairment, though his father claimed the injury was not debilitating enough to justify Vladimir’s idleness and reliance on his parents’ support. In 1932, twenty-five-year-old Vladimir was urged by his parents to leave the family home as they could not support all of their children due to the famine. Aggrieved by his forced departure, Vladimir broke window panes in his parents’ house and threatened to set his parents’ house on fire. Though Vladimir eventually obtained work at a butter factory in Baturyn, in 1935 Nikolai claimed that following his departure from the family home his son had resorted to beggary, extortion, and hooliganism.

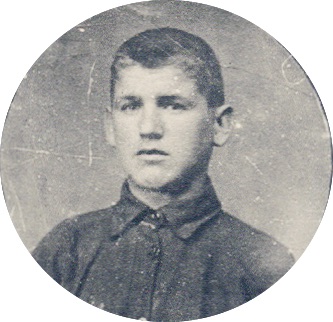

Portrait of Boris Bokan Details

Boris Bokan: Boris Bokan was born on June 26, 1909. He appears to have been the only one of the Bokan children to have heeded his father’s encouragement to engage with Tolstoyan philosophies, however briefly. Boris had also embraced pacifist values, although unlike his father, his inspiration came from an interest in anarchism rather than religion. Boris spent more than a year in prison for refusing to join the Soviet Army on the basis of his adherence to pacifism (1931-33). He was first imprisoned in the Far East and subsequently in Konotop, near Baturyn, and was released in March 1933.

Boris also learned photography from his father, and for a time worked as his assistant. In the trial documents he is described as a self-employed photographer. Although Boris is known to have assisted his father in his work, it is unclear to what extent he was involved in producing the photos in the file. It is notable, however, that Nikolai is featured in many photos and may well have been assisted by Boris in taking them.

It is unclear how Boris’ affinity toward his father’s religious and political beliefs affected his relationship with his disenchanted siblings. Gradually, Boris did become more sympathetic toward the Soviet regime, which caused tension with his father. Nevertheless, Boris was eventually arrested in 1937 alongside Nikolai, accused of anti-Soviet agitation. In an appeal against the verdict, Boris expressed his regret for refusing to join the Soviet Army, which had been presented as evidence of his anti-Soviet stance, and blamed his father’s negative influence. His appeal was refused, and he was sent to a labor camp in Sevvostlag, where he died in December 1939.

Boris also learned photography from his father, and for a time worked as his assistant. In the trial documents he is described as a self-employed photographer. Although Boris is known to have assisted his father in his work, it is unclear to what extent he was involved in producing the photos in the file. It is notable, however, that Nikolai is featured in many photos and may well have been assisted by Boris in taking them.

It is unclear how Boris’ affinity toward his father’s religious and political beliefs affected his relationship with his disenchanted siblings. Gradually, Boris did become more sympathetic toward the Soviet regime, which caused tension with his father. Nevertheless, Boris was eventually arrested in 1937 alongside Nikolai, accused of anti-Soviet agitation. In an appeal against the verdict, Boris expressed his regret for refusing to join the Soviet Army, which had been presented as evidence of his anti-Soviet stance, and blamed his father’s negative influence. His appeal was refused, and he was sent to a labor camp in Sevvostlag, where he died in December 1939.

Portrait of Konstantin Bokan Details

Konstantin Bokan: Konstantin was born in 1911. In the spring of 1933, after the Bokan family had gone without bread for more than ten months, Konstantin left the family home to take up work and residence at a collective farm. It is unclear whether he was asked to leave by his parents – as in the case of his elder brother Vladimir – or whether he left of his own volition. According to Nikolai, Konstantin was exposed to anti-religious Soviet propaganda while working on the collective farm, which prompted him to distance himself from his father. Nikolai also suspected that Konstantin’s emergent hostility was driven by frustration with his parents’ inability to provide for the family. Konstantin was overworked and poorly fed on the collective farm, where his supervisor suggested that he suppress his hunger by smoking cigarettes. Nikolai claimed that such poisoning contributed to Konstantin’s death. In June 1933, Konstantin died of starvation on a field of the collective farm. The photos created by Nikolai to document Konstantin’s death are the focus of the “Nikolai Bokan Collection.”

Portrait of Aleksandr Bokan Details

Aleksandr Bokan: Aleksandr was born in 1913. During the famine years, he was about twenty years old and lived with his parents in the family home. He moved out in 1936 to live in a separate apartment together with his younger siblings, Lev-Leonid and Anna. Aleksandr criticized his father’s decision to homeschool him and his siblings, claiming that this reduced their opportunities for employment within the Soviet institutional system later in life. It was rumored in the village that Aleksandr and Lev-Leonid convinced Anna to steal money, photo equipment, and some household items from their father, which she then sold to buy food. According to Nikolai, Aleksandr served in the Red Army, and at the time of Nikolai’s trial in 1937, was understood to have been stationed in the Far East.

Portrait of Lev-Leonid Bokan Details

Lev-Leonid Bokan: Lev-Leonid was born in 1915. At the time of the famine he was about eighteen years old and lived with his parents. He moved out in 1936 to live in an apartment together with his siblings Aleksandr and Anna. In his writings from the mid-1930s, Nikolai claimed that Lev-Leonid expressed contempt toward his father, accusing him of crippling his children both morally and physically. Nikolai claimed that in 1936, two years after Lev-Leonid and Aleksandr left the family home, the two sons came to their father to demand money and provisions. At around this time, the two sons are also said to have vandalized their family home as a further expression of their frustration with their father. According to Nikolai, Lev-Leonid had attended courses in Baturyn that qualified him in 1937 to become an accountant at the cooperative “Pervomai” (First of May), which sold bread. Nikolai suspected that Lev-Leonid was involved in embezzlement at the cooperative. At the time of Nikolai’s trial, Lev-Leonid was estranged from his father and was a witness in the investigation.

Portrait of Anna Bokan Details

Anna Bokan: Anna was born in 1919, and was the youngest child of Vasilina and Nikolai. During the famine years, she was about fourteen years old and lived with her parents. In the spring of 1933, Nikolai arranged for Anna to work at a neighbour’s farm, where she was to be fed as compensation. When it became clear that she was merely served skimmed milk mixed with water, Nikolai broke the arrangement.

Anna moved out in 1936 to live in an apartment together with her brothers Aleksandr and Lev-Leonid and ceased communicating with her father. Soon after, she began work at a local grocery store. According to Nikolai, it was around this time that Anna, prompted by her brothers, stole money from the family home as well as photography equipment and some household that were subsequently sold to buy food. Nikolai claimed that when he sought recourse from the authorities, they not only refused to convict but praised her for defying her father.

Anna was a witness in the investigation of Nikolai, and during her interrogation, referred to her father as an “enemy of the people.” She criticized him for refusing his children a proper education, and for forbidding them from working in Soviet institutions. She also stated that Nikolai forced his children to read Tolstoy’s writings and to adhere to his philosophy, to which they were strongly opposed.

Anna moved out in 1936 to live in an apartment together with her brothers Aleksandr and Lev-Leonid and ceased communicating with her father. Soon after, she began work at a local grocery store. According to Nikolai, it was around this time that Anna, prompted by her brothers, stole money from the family home as well as photography equipment and some household that were subsequently sold to buy food. Nikolai claimed that when he sought recourse from the authorities, they not only refused to convict but praised her for defying her father.

Anna was a witness in the investigation of Nikolai, and during her interrogation, referred to her father as an “enemy of the people.” She criticized him for refusing his children a proper education, and for forbidding them from working in Soviet institutions. She also stated that Nikolai forced his children to read Tolstoy’s writings and to adhere to his philosophy, to which they were strongly opposed.