Nikolai Bokan: a Biographical Essay

Tolstoyanism

Panels

IntroductionThe Criminal Case FileThe TrialThe Bokan FamilyNikolai Bokan's Life Pre-FamineFamine (1932-33)TolstoyanismPhotographyLinks

View the "Nikolai Bokan Collection"In addition to his photographic pursuits, Nikolai Bokan’s involvement in the Tolstoyan movement also figured prominently in the trial as evidence of his counter-revolutionary activity. The Tolstoyanism was based on the philosophical and religious writings of Leo Tolstoy, whose views were formed by the study of the ministry of Jesus. The movement promoted values of love for all, pacifism, through the study of the Ministry of Jesus, especially the Sermon on the Mount, vegetarianism, and moral improvement, and aspired for the attainment of a rural, self-sufficient livelihood.

In his memoir, Nikolai reflected that in his pre-Tolstoyan years, he was distracted from a purposeful and intellectually engaged lifestyle by a preoccupation with material possessions and entertainment. He claimed that in the early 1900s, after years of working in Odesa, he gradually developed an aversion to urban life, disenchanted by the seemingly “artificial” and “exploitative” relationships among city dwellers. Such sentiments were strengthened upon his engagement with the writings of Tolstoy, which prompted a number of changes in his life – namely, a return to a rural lifestyle, the pursuit of rigorous intellectual study, and the revival of a long-dormant religious consciousness. Nikolai’s initial engagement with Tolstoyanism was primarily conducted through self-study.

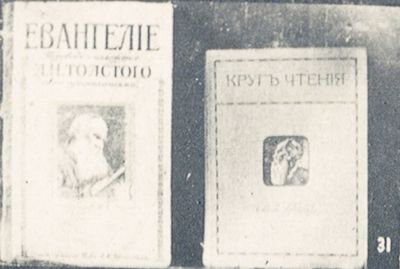

Along with other Tolstoyans, and many in Russia during the fall of 1917, Nikolai was initially sympathetic toward the Bolshevik-led October Revolution, and the promise of a new era of social experimentation that the revolution could incite.[2] Among Tolstoyans, optimism abounded that the new Bolshevik order would accommodate their ideals, and foster their aspirations for an autonomous, rural, self-sufficient livelihood within Soviet society. Nikolai even joined a local “circle of solidarity” of Bolshevik sympathizers, and assumed the role of secretary. Nikolai's sympathies soon diminished as the reality of Bolshevik rule became apparent. In 1926, Nikolai first read about Vladimir Cherkov, the head of the Tolstoyan society in Moscow, whose name he encountered in the newspaper, Izvestiya. Nikolai initiated a correspondence with Chertkov, requesting that Chertkov keep him abreast of developments in the movement. Nikolai was also in correspondence with the head of the Tolstoyan book publishing agency, Dobroliubov, from whom he received books by and about Leo Tolstoy. Nikolai also shared these books with other locals in Baturyn. Many received him with skepticism and considered his behaviour “counter-revolutionary.” According to Lev Bokan, his father was in contact with Chertkov and Dobroliubov until 1931 or 1932. Notably, this coincided with the Soviet authorities’ intensifying repressions of Tolstoyans and other sectarian movements. The correspondences were among the documents confiscated as part of his trial.

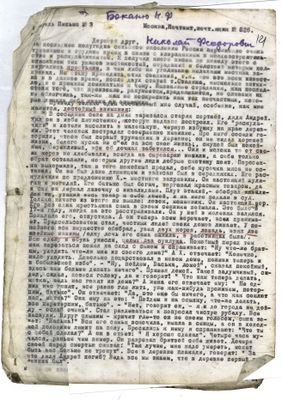

Along with many Tolstoyans, Nikolai identified as Christian without belonging to an institutional church. Although he strongly opposed the anti-religious sentiments propagated by the Soviet system, he also believed that religious institutions and practices wrongly emphasized custom over a focus on God and faith. Nikolai was especially disturbed by the widespread anti-religious sentiment propagated by Soviet authorities beginning in the late 1920s as a means of disseminating atheism and promoting loyalty to the state. These anti-religious campaigns coincided with the beginning of the forced mass collectivization of agriculture. In the correspondences with Chertkov, Nikolai received updates on evolving relations between the Tolstoyans and the Soviet authorities, and the undermining impact of collectivization on their communities. During the trial, Nikolai was accused of receiving directives from Chertkov, which he denied.

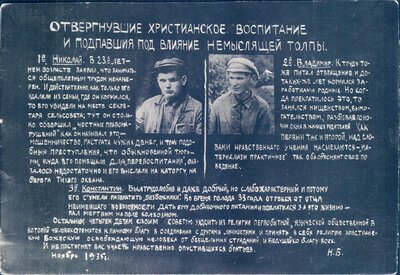

Nikolai homeschooled most of his children due to his distrust of the state and what he perceived as the “corrupting” influence of the anti-religious curriculum. However, homeschooling did not prove wholly advantageous. In his memoir, Nikolai reflected on the impact of hunger on his children's education: “When people are forced to starvation, the discussion of proper upbringing, and especially education, becomes irrelevant, the priority is to find food.” Eventually, Nikolai resigned himself to the impossibility of saving his children’s generation from “the corrupting spirit of the time.” Though he regretted the deficiencies in their homeschooling, he was consoled that their lack of education prevented them from assuming “exploitative” positions in society. As young adults, his children grew to resent their homeschooling, which they claimed had prevented them access to certain advantages and jobs in Soviet society.

Nikolai's efforts to impose Tolstoyan teachings on his family members were also met with resistance, and tensions regarding these matters boiled over between Nikolai and his children in the mid-1930s. Over the years, Nikolai also sought to disseminate Tolstoyan teachings to neighbours and acquaintances, though it appears his efforts merely reinforced perceptions of his eccentricities, and perhaps reduced sympathies toward Nikolai’s struggles to provide for his family.

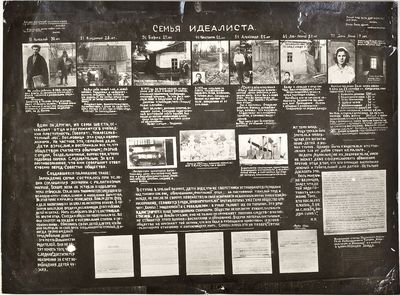

Among Nikolai's children, only Boris appears to have briefly engaged with Tolstoyanism. Nikolai’s three youngest children – Aleksandr, Lev-Leonid, and Anna – left the family home in 1936, initiating an estrangement with their father. Nikolai continued to send them letters and display boards, coaxing them to return home and embrace a spiritual lifestyle. A selection of the boards is included in the “Nikolai Bokan Collection,” and reveals how the famine figured in Nikolai’s perception of these broader family dynamics.

In his memoir, Nikolai reflected that in his pre-Tolstoyan years, he was distracted from a purposeful and intellectually engaged lifestyle by a preoccupation with material possessions and entertainment. He claimed that in the early 1900s, after years of working in Odesa, he gradually developed an aversion to urban life, disenchanted by the seemingly “artificial” and “exploitative” relationships among city dwellers. Such sentiments were strengthened upon his engagement with the writings of Tolstoy, which prompted a number of changes in his life – namely, a return to a rural lifestyle, the pursuit of rigorous intellectual study, and the revival of a long-dormant religious consciousness. Nikolai’s initial engagement with Tolstoyanism was primarily conducted through self-study.

Along with other Tolstoyans, and many in Russia during the fall of 1917, Nikolai was initially sympathetic toward the Bolshevik-led October Revolution, and the promise of a new era of social experimentation that the revolution could incite.[2] Among Tolstoyans, optimism abounded that the new Bolshevik order would accommodate their ideals, and foster their aspirations for an autonomous, rural, self-sufficient livelihood within Soviet society. Nikolai even joined a local “circle of solidarity” of Bolshevik sympathizers, and assumed the role of secretary. Nikolai's sympathies soon diminished as the reality of Bolshevik rule became apparent. In 1926, Nikolai first read about Vladimir Cherkov, the head of the Tolstoyan society in Moscow, whose name he encountered in the newspaper, Izvestiya. Nikolai initiated a correspondence with Chertkov, requesting that Chertkov keep him abreast of developments in the movement. Nikolai was also in correspondence with the head of the Tolstoyan book publishing agency, Dobroliubov, from whom he received books by and about Leo Tolstoy. Nikolai also shared these books with other locals in Baturyn. Many received him with skepticism and considered his behaviour “counter-revolutionary.” According to Lev Bokan, his father was in contact with Chertkov and Dobroliubov until 1931 or 1932. Notably, this coincided with the Soviet authorities’ intensifying repressions of Tolstoyans and other sectarian movements. The correspondences were among the documents confiscated as part of his trial.

Along with many Tolstoyans, Nikolai identified as Christian without belonging to an institutional church. Although he strongly opposed the anti-religious sentiments propagated by the Soviet system, he also believed that religious institutions and practices wrongly emphasized custom over a focus on God and faith. Nikolai was especially disturbed by the widespread anti-religious sentiment propagated by Soviet authorities beginning in the late 1920s as a means of disseminating atheism and promoting loyalty to the state. These anti-religious campaigns coincided with the beginning of the forced mass collectivization of agriculture. In the correspondences with Chertkov, Nikolai received updates on evolving relations between the Tolstoyans and the Soviet authorities, and the undermining impact of collectivization on their communities. During the trial, Nikolai was accused of receiving directives from Chertkov, which he denied.

Nikolai homeschooled most of his children due to his distrust of the state and what he perceived as the “corrupting” influence of the anti-religious curriculum. However, homeschooling did not prove wholly advantageous. In his memoir, Nikolai reflected on the impact of hunger on his children's education: “When people are forced to starvation, the discussion of proper upbringing, and especially education, becomes irrelevant, the priority is to find food.” Eventually, Nikolai resigned himself to the impossibility of saving his children’s generation from “the corrupting spirit of the time.” Though he regretted the deficiencies in their homeschooling, he was consoled that their lack of education prevented them from assuming “exploitative” positions in society. As young adults, his children grew to resent their homeschooling, which they claimed had prevented them access to certain advantages and jobs in Soviet society.

Nikolai's efforts to impose Tolstoyan teachings on his family members were also met with resistance, and tensions regarding these matters boiled over between Nikolai and his children in the mid-1930s. Over the years, Nikolai also sought to disseminate Tolstoyan teachings to neighbours and acquaintances, though it appears his efforts merely reinforced perceptions of his eccentricities, and perhaps reduced sympathies toward Nikolai’s struggles to provide for his family.

Among Nikolai's children, only Boris appears to have briefly engaged with Tolstoyanism. Nikolai’s three youngest children – Aleksandr, Lev-Leonid, and Anna – left the family home in 1936, initiating an estrangement with their father. Nikolai continued to send them letters and display boards, coaxing them to return home and embrace a spiritual lifestyle. A selection of the boards is included in the “Nikolai Bokan Collection,” and reveals how the famine figured in Nikolai’s perception of these broader family dynamics.

Tolstoy Books Details

Letter from Vladimir Chertkov addressed to Nikolai Bokan Details

Bokan's Children standing by a Bookshelf Details

Photo Display Board: “Those who rejected a Christian upbringing and fell under the influence of a mindless crowd” Details

Photo Display Board: “The Family of an Idealist” Details