Alexander Wienerberger: a Biographical Exhibit

Return to Austria: 1934-1935

Contents

SummaryPart I: Vienna to the USSRKharkivKharkiv overviewReturn to Austria: 1934-1935Austria: The Later YearsPart II: From obscurity to distinction – The early yearsInto the new millenniumRecognitionOngoing legacyEndnotesWork CitedLinks

Download text (PDF)View the "Alexander Wienerberger: Innitzer Album" collectionView the "Alexander Wienerberger: Beyond the Innitzer album" collectionReturn to Austria

“ ‘Please, please, dear comrade’ (he actually dropped to both knees and raised his hands in the air), ‘don't go away from here before you've promised me to raise your voice loudly to accuse those murderers before the court of the world's conscience!’ ‘Yes,’ I said, ‘I promise you, here you have my hand on it.‘"6

Following his year in Kharkiv, Wienerberger resolved to leave the Soviet Union permanently. He visited a health sanatorium in Crimea, took a brief winter assignment in Moscow to work out his exit strategy, and returned to Vienna in 1934.7 He despised the ever-increasing hypocrisy and shocking brutality of the Bolshevik regime so evident in Ukraine and determined to crusade against it upon returning home. He was constrained to some degree, however, by Austria’s reluctance to disturb its diplomatic and economic relationship with the USSR or to put Austrian citizens in the USSR at risk.8 When Austria’s Ambassador Heinrich Pacher offered to send Wienerberger’s photos back to Vienna via diplomatic mail in 1933 to avoid the risk of confiscation "by the greedy hands of the GPU,"9 there were strings attached. Wienerberger had to promise, in essence, to reflect Austria’s interests in any public use of those photographs.10

In spite of these limitations, in March 1934 he had barely returned home before publishing an article “Das Land des Hungers und des Todes” [The Land of Starvation and Death] in the Austrian newspaper Salzburger Chronik, under the alias Otto Alexander, but without any photographs.11 He also embarked almost immediately on a series of lectures about his experiences in the Soviet Union.

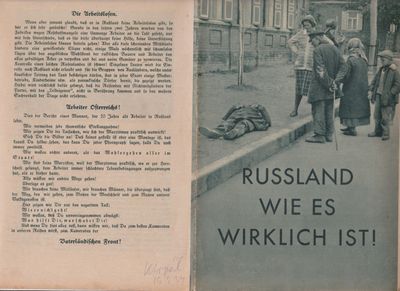

His photo documentation sparked the interest of Austria’s Vaterländische Front (the ruling far right nationalist anti-Nazi party). In 1934, it published an anti-Bolshevik brochure geared toward the working classes, Russland wie es wirklich ist [Russia as it really is], featuring Wienerberger’s narrative and illustrated exclusively with his photos from Ukraine, but without attribution. The Soviet response was swift and angry, denouncing the “lying and false claims.”12 Wienerberger’s unattributed photographs also appeared in at least one of several “Brüder in Not!” [Brethren in Need] pamphlets13 published by both secular and evangelical organizations in Germany and Austria.

Recently, investigative journalists and researchers14,15,16 have come upon correspondence indicating that in 1934, Wienerberger contacted the Ukrainian Bureau in London, attempting to find buyers in the English market for his Kharkiv photos. As he had in Austria, he maintained a level of anonymity for self-protection. At least five of his photos, attributed to “Otto Alexander,” were purchased by a photo agency in late 1934,17 but no evidence of their publication has come to light.

“Many Europeans observed the terrible hunger tragedy of southern Russia in 1933; but few of them know that it was a well-organised mass murder, with no equal to its extent and bestiality in world history.”18

Wienerberger’s anti-Bolshevik activities also caught the attention of both Ewald Ammende, Head of the European Congress on Nationalities, and Cardinal Theodor Innitzer, the Roman Catholic archbishop of Vienna. Ammende and the Cardinal sought to garner international support for their inter-denominational campaign to assist the victims of starvation in the USSR, particularly those in Ukraine and the German colonies in Russia.19 The campaign was vehemently condemned by Moscow as capitalist propaganda and ultimately failed to gain significant support in the West.20 Nevertheless, as a token of appreciation to the Cardinal for his efforts, Wienerberger compiled an album of twenty-five photographs depicting Kharkiv’s “tragedy of famine,”21 which he presented, with his signature. (For more details on the album, see “Alexander Wienerberger: Innitzer Album, a Collection Note” in this Directory: http://vitacollections.ca/HREC-holodomorphotodirectory/3630343/data )

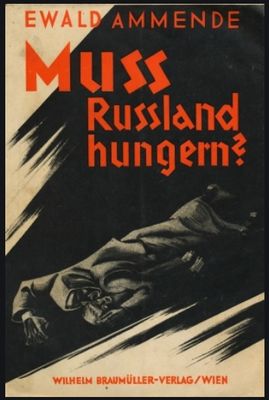

For his part, Ammende, who had in July 1933 already sounded the alarm about famine 22 in an article in the Austrian press,23 went on to write Muss Russland Hungern24 [Must Russia Starve]), a full-length account, damning in its objectivity and insightfulness, illustrated exclusively with twenty-one of Wienerberger’s photographs from Ukraine. The book was published in Austria to some acclaim in 1935 and elicited strong rebuke from the Soviet government, embarrassing Austrian officials who preferred not to alienate the USSR at that time. The 1935 edition was followed by an English translation: Human Life in Russia25 in 1936, after Ammende’s untimely and mysterious death while traveling in China earlier that year.26 The English language edition (reprinted in the US in 1984)27 unfortunately removed half of the Wienerberger photos and added others – some of possible legitimacy from the North Caucasus regions, but others definitely from the 1920s famine in Russia and Ukraine.

“ ‘Please, please, dear comrade’ (he actually dropped to both knees and raised his hands in the air), ‘don't go away from here before you've promised me to raise your voice loudly to accuse those murderers before the court of the world's conscience!’ ‘Yes,’ I said, ‘I promise you, here you have my hand on it.‘"6

Following his year in Kharkiv, Wienerberger resolved to leave the Soviet Union permanently. He visited a health sanatorium in Crimea, took a brief winter assignment in Moscow to work out his exit strategy, and returned to Vienna in 1934.7 He despised the ever-increasing hypocrisy and shocking brutality of the Bolshevik regime so evident in Ukraine and determined to crusade against it upon returning home. He was constrained to some degree, however, by Austria’s reluctance to disturb its diplomatic and economic relationship with the USSR or to put Austrian citizens in the USSR at risk.8 When Austria’s Ambassador Heinrich Pacher offered to send Wienerberger’s photos back to Vienna via diplomatic mail in 1933 to avoid the risk of confiscation "by the greedy hands of the GPU,"9 there were strings attached. Wienerberger had to promise, in essence, to reflect Austria’s interests in any public use of those photographs.10

In spite of these limitations, in March 1934 he had barely returned home before publishing an article “Das Land des Hungers und des Todes” [The Land of Starvation and Death] in the Austrian newspaper Salzburger Chronik, under the alias Otto Alexander, but without any photographs.11 He also embarked almost immediately on a series of lectures about his experiences in the Soviet Union.

His photo documentation sparked the interest of Austria’s Vaterländische Front (the ruling far right nationalist anti-Nazi party). In 1934, it published an anti-Bolshevik brochure geared toward the working classes, Russland wie es wirklich ist [Russia as it really is], featuring Wienerberger’s narrative and illustrated exclusively with his photos from Ukraine, but without attribution. The Soviet response was swift and angry, denouncing the “lying and false claims.”12 Wienerberger’s unattributed photographs also appeared in at least one of several “Brüder in Not!” [Brethren in Need] pamphlets13 published by both secular and evangelical organizations in Germany and Austria.

Recently, investigative journalists and researchers14,15,16 have come upon correspondence indicating that in 1934, Wienerberger contacted the Ukrainian Bureau in London, attempting to find buyers in the English market for his Kharkiv photos. As he had in Austria, he maintained a level of anonymity for self-protection. At least five of his photos, attributed to “Otto Alexander,” were purchased by a photo agency in late 1934,17 but no evidence of their publication has come to light.

“Many Europeans observed the terrible hunger tragedy of southern Russia in 1933; but few of them know that it was a well-organised mass murder, with no equal to its extent and bestiality in world history.”18

Wienerberger’s anti-Bolshevik activities also caught the attention of both Ewald Ammende, Head of the European Congress on Nationalities, and Cardinal Theodor Innitzer, the Roman Catholic archbishop of Vienna. Ammende and the Cardinal sought to garner international support for their inter-denominational campaign to assist the victims of starvation in the USSR, particularly those in Ukraine and the German colonies in Russia.19 The campaign was vehemently condemned by Moscow as capitalist propaganda and ultimately failed to gain significant support in the West.20 Nevertheless, as a token of appreciation to the Cardinal for his efforts, Wienerberger compiled an album of twenty-five photographs depicting Kharkiv’s “tragedy of famine,”21 which he presented, with his signature. (For more details on the album, see “Alexander Wienerberger: Innitzer Album, a Collection Note” in this Directory: http://vitacollections.ca/HREC-holodomorphotodirectory/3630343/data )

For his part, Ammende, who had in July 1933 already sounded the alarm about famine 22 in an article in the Austrian press,23 went on to write Muss Russland Hungern24 [Must Russia Starve]), a full-length account, damning in its objectivity and insightfulness, illustrated exclusively with twenty-one of Wienerberger’s photographs from Ukraine. The book was published in Austria to some acclaim in 1935 and elicited strong rebuke from the Soviet government, embarrassing Austrian officials who preferred not to alienate the USSR at that time. The 1935 edition was followed by an English translation: Human Life in Russia25 in 1936, after Ammende’s untimely and mysterious death while traveling in China earlier that year.26 The English language edition (reprinted in the US in 1984)27 unfortunately removed half of the Wienerberger photos and added others – some of possible legitimacy from the North Caucasus regions, but others definitely from the 1920s famine in Russia and Ukraine.