Alexander Wienerberger: a Biographical Exhibit

Part II: From obscurity to distinction – The early years

Contents

SummaryPart I: Vienna to the USSRKharkivKharkiv overviewReturn to Austria: 1934-1935Austria: The Later YearsPart II: From obscurity to distinction – The early yearsInto the new millenniumRecognitionOngoing legacyEndnotesWork CitedLinks

Download text (PDF)View the "Alexander Wienerberger: Innitzer Album" collectionView the "Alexander Wienerberger: Beyond the Innitzer album" collectionPart II: From obscurity to distinction

The early years The first known instance of Alexander Wienerberger’s name appearing in connection with his published writing and photographs did not occur until late 1938, when the Salzburger Volksblatt ran his serialized memoir “Abenteuer in Sowjetrussland,” featuring seven of his Kharkiv photos. The series was subsequently published in book format as Hart auf hart in 1939.35 Dismissed, perhaps, as typical Nazi anti-Bolshevik propaganda following WWII, Hart auf Hart with its forty-three authentic Kharkiv photos can now be found in only a small number of scholarly institutions worldwide. Decades later, Human Life in Russia, the 1936 English edition of Ammende’s Muss Russland Hungern, was reprinted in the US in 1984 with a forward by Holodomor scholar James Mace. It was widely distributed in the Ukrainian diaspora and among historians of the Ukraine famine. Unfortunately, because the English edition contained 1920s photos misidentified as from the Holodomor and others of unsubstantiated origin along with a few of Wienerberger’s unattributed photographs, the publication of this book cast the entire photographic content in a dubious light.

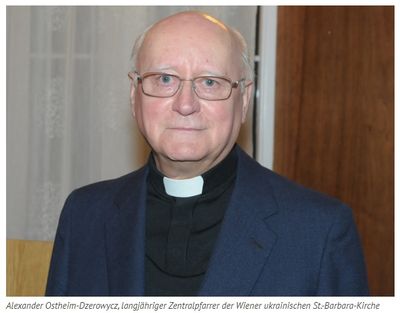

However, also in the early to mid 1980s, Prelate Ostheim-Dzerowicz of Vienna discovered the signed album presented by Wienerberger to Cardinal Innitzer among the Cardinal’s papers in Vienna’s Diocesan Archives.36 In 1985, copies of these photographs along with basic information about Wienerberger and matching photos derived from his memoir were shared with members of the International Commission of Inquiry into the 1932-33 Famine in Ukraine and later submitted as supporting evidence for that Commission’s findings.37 (For more details see: “Alexander Wienerberger: Innitzer Album. A Collection Note” in this Directory : http://vitacollections.ca/HREC-holodomorphotodirectory/3630343/data )

Around the same time, Canadian researcher Marco Carynnyk was uncovering a wealth of information in the British Foreign Office Files38 on the deliberate inaction of the West with regard to Ukraine’s famine. One of the documents, submitted in July 1934 by the Austrian consulate in Kharkiv, mentions Wienerberger and describes his photographs of death and destitution taken in Kharkiv. This document was subsequently reprinted in The Foreign Office and the Famine compilation).39 Interestingly, Wienerberger is named as “Otto” in the diplomat’s report. However, Carynnyk’s notes correctly surmise that the photographs that were being referenced and which appeared anonymously the following year in Ammende’s Muss Russland Hungern, were indeed Alexander Wienerberger’s. Carynnyk was also the first to point out the discrepancy between the authentic Holodomor-era photos in the German original and the photos found in the English edition, Human Life in Russia.40

Neither the International Commission’s revelations about Wienerberger’s photographs nor Carynnyk’s corroborating research reached a broad audience, however. This information reached neither Robert Conquest prior to the publication of his ground-breaking study of the famine, Harvest of Sorrow41 nor the US Commission on the Ukraine Famine in time for consideration in preparing its report.42 In the ensuing decades, the photographs began appearing sporadically in print and media, but for the most part without attribution.

The early years The first known instance of Alexander Wienerberger’s name appearing in connection with his published writing and photographs did not occur until late 1938, when the Salzburger Volksblatt ran his serialized memoir “Abenteuer in Sowjetrussland,” featuring seven of his Kharkiv photos. The series was subsequently published in book format as Hart auf hart in 1939.35 Dismissed, perhaps, as typical Nazi anti-Bolshevik propaganda following WWII, Hart auf Hart with its forty-three authentic Kharkiv photos can now be found in only a small number of scholarly institutions worldwide. Decades later, Human Life in Russia, the 1936 English edition of Ammende’s Muss Russland Hungern, was reprinted in the US in 1984 with a forward by Holodomor scholar James Mace. It was widely distributed in the Ukrainian diaspora and among historians of the Ukraine famine. Unfortunately, because the English edition contained 1920s photos misidentified as from the Holodomor and others of unsubstantiated origin along with a few of Wienerberger’s unattributed photographs, the publication of this book cast the entire photographic content in a dubious light.

However, also in the early to mid 1980s, Prelate Ostheim-Dzerowicz of Vienna discovered the signed album presented by Wienerberger to Cardinal Innitzer among the Cardinal’s papers in Vienna’s Diocesan Archives.36 In 1985, copies of these photographs along with basic information about Wienerberger and matching photos derived from his memoir were shared with members of the International Commission of Inquiry into the 1932-33 Famine in Ukraine and later submitted as supporting evidence for that Commission’s findings.37 (For more details see: “Alexander Wienerberger: Innitzer Album. A Collection Note” in this Directory : http://vitacollections.ca/HREC-holodomorphotodirectory/3630343/data )

Around the same time, Canadian researcher Marco Carynnyk was uncovering a wealth of information in the British Foreign Office Files38 on the deliberate inaction of the West with regard to Ukraine’s famine. One of the documents, submitted in July 1934 by the Austrian consulate in Kharkiv, mentions Wienerberger and describes his photographs of death and destitution taken in Kharkiv. This document was subsequently reprinted in The Foreign Office and the Famine compilation).39 Interestingly, Wienerberger is named as “Otto” in the diplomat’s report. However, Carynnyk’s notes correctly surmise that the photographs that were being referenced and which appeared anonymously the following year in Ammende’s Muss Russland Hungern, were indeed Alexander Wienerberger’s. Carynnyk was also the first to point out the discrepancy between the authentic Holodomor-era photos in the German original and the photos found in the English edition, Human Life in Russia.40

Neither the International Commission’s revelations about Wienerberger’s photographs nor Carynnyk’s corroborating research reached a broad audience, however. This information reached neither Robert Conquest prior to the publication of his ground-breaking study of the famine, Harvest of Sorrow41 nor the US Commission on the Ukraine Famine in time for consideration in preparing its report.42 In the ensuing decades, the photographs began appearing sporadically in print and media, but for the most part without attribution.