Pro History Project: History by Design

I. Rural Life, Industries and Transportation

Panels

Pro History ProjectOral HistoriesFrom The Heartland: Ninteenth Century Buildings of Victoria CountyAcknowledgementsIntroductionThe Heartland in PerspectiveI. Rural Life, Industries and TransportationII. CommunitiesIII. EstatesIV. Gathering PlacesConclusionBibliographyMissing Slides and PhotographsLinks

Pro History Colour SlidesOral HistoriesPro History Black & WhiteTo trace out the development of rural building, as expressed first in materials and only secondarily in an imitation of English or American architectural fashions, is to reveal as well the hardships and fruits of settlement. Rural architecture, then, is as much a social document of agriculture’s material development as it is a mirror of the popular assimilation of intellectual currents of taste in building.

The process of settlement demanded a fairly repetitive pattern of building. The usual progression was to begin with the log cabin or shanty and then, as the means offered, to build in frame or brick or in a combination of both. Occasionally some settlers built in stone. But, as John Langton noted, the expense of doing so, and of finding skilled craftsmen, precluded its use by most settlers.

Wood, of course, was the most common and cheapest material available. From the cedar log to the pine plank, wood offered a building material that was both easily worked and ready at hand. Wood, however, was also the building material most susceptible to damage caused by harsh climactic change. Many of the first settlers from Great Britain learned only after their first attempt at building that the sills of log and frame houses had to be raised off the ground by stone foundations to avoid the havoc winter freezes and spring thaws could wreak on log walls, chinking and floors.

The process of settlement demanded a fairly repetitive pattern of building. The usual progression was to begin with the log cabin or shanty and then, as the means offered, to build in frame or brick or in a combination of both. Occasionally some settlers built in stone. But, as John Langton noted, the expense of doing so, and of finding skilled craftsmen, precluded its use by most settlers.

Wood, of course, was the most common and cheapest material available. From the cedar log to the pine plank, wood offered a building material that was both easily worked and ready at hand. Wood, however, was also the building material most susceptible to damage caused by harsh climactic change. Many of the first settlers from Great Britain learned only after their first attempt at building that the sills of log and frame houses had to be raised off the ground by stone foundations to avoid the havoc winter freezes and spring thaws could wreak on log walls, chinking and floors.

Plate 1, log cabin, Ops township Details

The most common cabin was the plain, perpendicular one cornered with the square lap key with either a chimney in the centre or one at each gable end (Plate 1). This is an example from Ops Township; note the degree to which the cabin has settled. This could have been accentuated by the practice of heaping up sods next to the wall for insulation and drainage.

Plate 3, Log cabin, Emily Township Details

Plate 3 shows a close-up detail of the method of cornering known as square lapping. This square lap is a simple overlap of log ends that could easily be shifted by heat, cold or dampness.

2. Log cabin, Eldon Township, private dwelling Details

Cabins of better craftsmanship exhibit a different method of cornering as can be seen in the cabin from Eldon Township in Plate 2. This is called dovetailing.

Plate 4, Grandy Rd, Coboconk, dovetail detailing Details

The logs were cut in downward angles (see Plate 4, a detail from a log house in Coboconk, Bexley) so as to allow rain and snow to run off before rotting or pulling the walls apart through water gathering or freezing in the joint. As well, dovetailing worked to pull the logs together in such a way as to resist settling and to minimize the need for chinking, unlike the square lap key. Military dovetailing was of such craftsmanship that no chinking was needed; as is evidenced in the blockhouses built to protect the Rideau Canal.

Cabins in the southern part of the county that survived as houses for longer periods of time, beyond the normal five to eight years of use before being relegated to the barnyard, have been ornamented with false wooden pillars and window decorations of classic derivation. These decorations aid in dating them since cabins are normally an indication of the period of settlement rather than of any particular time.

Plate 6, Log cabin, Carden Township Details

If a family could not afford to immediately move from a log to a frame house, the solution could be as in Plate 6 (Carden Township). Here a dovetailed log house has been framed over to upgrade one’s social status and perhaps to add to its insulative value. This is a particularly interesting homestead since it contains within a small area the original homestead of log house, log outbuildings and barn complex and, to the east, the later frame one and a half storey house with a gambrel roof frame barn.

Log cabin, Grandy Rd, Coboconk Details

The next step up for the settler family was the move to a frame house as their fortunes improved from the sale of wheat, dairy products and seasonal labour. The usual plan was a perpendicular one and a half storey house with a centre gable directly over the front door and chimneys at each gable end for wood stoves. The one and a half storey house was an indigenous product of Ontario’s nineteenth century tax structure that discriminated against two storey and multi-windowed houses. In effect, large houses and the number of fireplaces and windows were regarded as luxuries to be taxed. Though this practice ended in 1853, a firm tradition of one and a half storey buildings had been created.

Plate 8, Frame house, Mariposa Township, private dwelling Details

A good example of this is the overlaid frame from Mariposa in Plate 8 with a gothic window in the gable as decoration. Another good horizontal frame that has remained uncovered is on the northeast corner of the hamlet of Bexley. It has remained unpainted with its original wooden pilasters and boarded in sidelights.

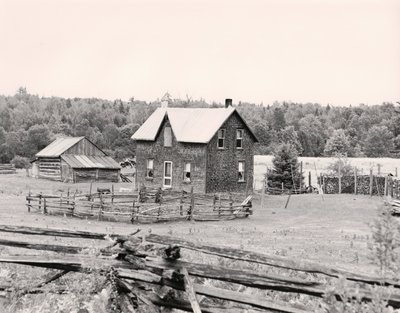

Plate 9, Farmhouse, Somerville Township Details

During the nineteenth century, frame buildings outstripped all others in numbers (see Graph III on page (--). But it is rare now to find any that have not been substantially altered. One such unaltered example is the shingled frame house in Somerville in Plate 9. Once such homesteads, with their surrounding rail fences and large wood piles, were a common sight. Now they are to be met only on the furthest back concessions.

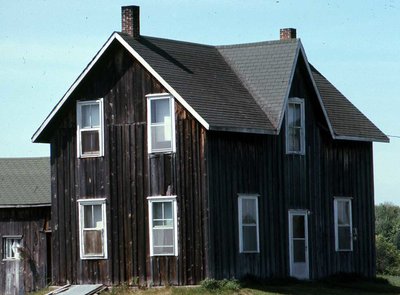

Plate 11, Frame house, Dalton Township, private dwelling Details

An interesting variation in frame building was the picturesque board and batten house (see Plate 11). Board and batten is a form of vertical framing with the vertical space between each board covered by a thin batten. The batten could be a plain strip of wood or factory moulded to emphasize its picturesque function. Both battens added a vertical textural rhythm to the plain frame. Our example from Dalton is a strikingly spare one.

Plate 115, Anglican Church, Sherwood Street, Bobcaygeon Details

But for a more picturesque effect see Christ Church in Plate 115.

The frame house also served to introduce the countryside to architectural fashions and styles imported from Europe, Great Britain, and the United States. But these styles were only incorporated into the design as features to embellish the plain rectangular design. Rarely did a house reflect one complete style in all of its details. These features were added piecemeal in the form of window shapes, bays, barge board, treillage, bracketing, etc…

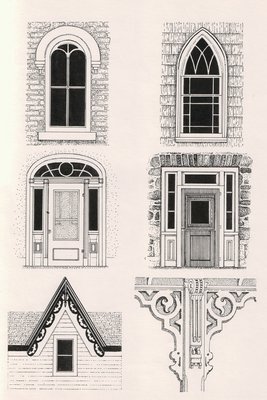

Drawing of Windows and Doors Details

If one looks at the drawings on the following page, the reader can see some of these more common features. At the top are the two most common window designs, the round headed (Italianate) and painted (Gothic). In the centre are door entablatures. On the left is a Georgian transom (see Plate 7) from an 1839 frame house in Emily. The Georgian transom, i.e. the glass above the door, was either fan shaped or elliptical. The more common neo-classic transom is a square design that can be found throughout the county.

The glass transom and sidelights are usually features associated with the earliest frame and brick houses. Their function was to light the hallway. But with better lighting in the shape of coal oil lamps, the transom and sidelights were eliminated since they were a great source of heat loss. In Victoria County’s case, there are relatively few, if no more than two or three, Georgian transoms since the area was not settled until the 1830s and 1840s when the Georgian style was being eclipsed by early Victorian trends.

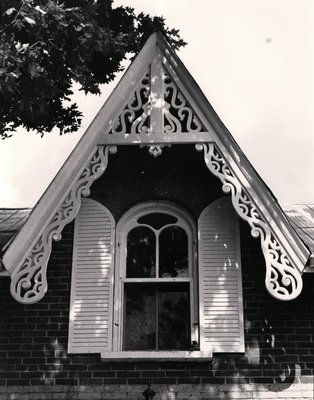

At the bottom are two of the most common decorative features of nineteenth century building. On the lower left we have what is commonly known as ‘gingerbread’, though it is known in architecture as bargeboard. Bargeboard reached its peak in this area from 1850 to 1880 especially in the lumbering villages and in the prosperous farming areas of Mariposa, Ops and in such villages as Little Britain, Oakwood and, especially, Woodville.

The glass transom and sidelights are usually features associated with the earliest frame and brick houses. Their function was to light the hallway. But with better lighting in the shape of coal oil lamps, the transom and sidelights were eliminated since they were a great source of heat loss. In Victoria County’s case, there are relatively few, if no more than two or three, Georgian transoms since the area was not settled until the 1830s and 1840s when the Georgian style was being eclipsed by early Victorian trends.

At the bottom are two of the most common decorative features of nineteenth century building. On the lower left we have what is commonly known as ‘gingerbread’, though it is known in architecture as bargeboard. Bargeboard reached its peak in this area from 1850 to 1880 especially in the lumbering villages and in the prosperous farming areas of Mariposa, Ops and in such villages as Little Britain, Oakwood and, especially, Woodville.

Plate 7, Georgian Transom, 1839, Frame house, Emily Township Details

There were innumerable fancy designs cut either by hand or later in a factory. The most popular design was the ‘loop’ style, as can be seen in this drawing. Bargeboard eventually retreated up the gable as the century drew to a close and was replaced by solid boards with some factory incised design or retreated to a tiny triangle of turned wood surrounding the kingpost.

On the lower right the reader can see an example of what is technically known as treillage. Treillage was porch decoration cut and sawed to imitate, originally, the picturesque effect climbing trellises and rose bushes produced when allowed to entwine themselves about the porch’s columns. As the century wore on, treillage designs became more and more stylized, like bargeboard, and thus further removed from their models in nature.

On the lower right the reader can see an example of what is technically known as treillage. Treillage was porch decoration cut and sawed to imitate, originally, the picturesque effect climbing trellises and rose bushes produced when allowed to entwine themselves about the porch’s columns. As the century wore on, treillage designs became more and more stylized, like bargeboard, and thus further removed from their models in nature.

Plate 98, Case Manor, Boyd Estate, Bobcaygeon Details

Treillage also served to express such influences as Oriental porch designs, as can be seen in W.T.C. Boyd’s house (Plate 98) and in Woodville, and even Moorish effects produced by wooden bobbins on slender canes in order to give shade. There is one particularly fine example of this on Bond St. in Lindsay.

Cambridge Street North, Lindsay, private dwelling Details

Our drawing, in fact, is taken directly from a house on Cambridge St. North in Lindsay.

Plate 15, Bargeboard, Brick Frame House, Fenelon Township Details

From these drawings, then, the reader can see that frame and brick houses have drawn upon features from certain styles, ranging from Gothic barge board to Italianate windows (see Plate 15).

Plate 12, Frame house, Verulam Township Details

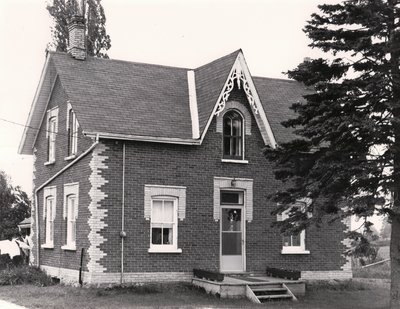

Often the frame farmhouse was built to be later bricked over when the settler could afford to do so. If one compares Plate 12 and 13, one can see how the essential plan of the perpendicular one and a half storey frame house could be built up in stages to the relatively affluent brick house with its rich decorative brick work in contrasting colours, textures and designs.

Plate 13, South Portage Road, Eldon Township, private dwelling Details

The idea of using brick itself as a means of decoration had originated in Britain. But it had never caught on there as it did in Canada where all kinds of elaborate designs were invented. One was the ‘drop’ style which was particularly popular in Central Ontario. The ‘drop’ style can be identified by the nipple hanging from the brick shouldering around the window heads, as in Plate 13. This popular brick design can be found in farmhouses, schools, churches, etc. throughout the county.

Other popular brick designs were the false keying placed over windows, segmented zigzag or square patterns outlining the corners (see Plates 13, 14, 17 and 21), a course of patterned or plain brick that ran around the face of the house between the first and second storey (see Plates 16 and 18), and rarer designs left by the individual bricklayer.

Plate 16, Farm house, Ops Township, private dwelling Details

Some of the best examples are the huge chalices worked on the walls of a house in Ops (Plate 16) and certain geometric designs such as diamond lozenges, alternating V’s or red and yellow brick in the front gable

Plate 14, Farm house, Mariposa Township Details

and the patterned triangle worked in the gable end of Plate 14. There are two other houses that exhibit this same feature. But, interestingly, they are all confined to an area of a few square miles in southwest Mariposa. This would seem to suggest the work of only one mason or else a feature borrowed by a few neighbours from the first house to use the triangle. This is a very good example of the kind of variation possible in vernacular and purely local building.

Plate 17, Farm house, Emily Township Details

Later frame and brick houses drew away from the one and a half storey tradition as growing prosperity allowed time to build larger houses based on an L or T shaped plan. These plans allowed for the placement of summer kitchens to the rear of the house to minimize the heat of the wood cooking stove in summer. The full two storey house was often adorned with a raised central projection that also worked to break up the plain square design (as in Plate 17). And, as well as vernacular variations in the stolid Canadian farmhouse, there are occasional examples of building drawn directly from architects’ drawings published in such newspapers as the Canada Farmer.

Plate 18, "Cottage Gothic" farm house, Emily Township Details

One such picturesque example is the ‘Cottage Gothic’ in Plate 18; a pleasing symmetrical arrangement of two small gothic windows, with smaller gables, flanking a larger gothic window under a larger gable.

Plate 21, Farm house, Eldon Township, private dwelling Details

By the turn of the century, full two storey farmhouses were being built with hip vault roofs and decorated with elaborately cut and turned factory woodwork as in Plate 21.

Plate 22, Farm house, Verulam Township, private dwelling Details

There were even huge farmhouses - mansions decorated with cut stone and elaborate roof lines as in Plate 22 from Verulam Township or like the Isaac’s ‘Glanvilla’ in Fenelon Township.

Houses built in stone, in contrast to frame or brick, are far rarer and less variegated since they were confined to the earliest period of settlement (i.e. the southern townships) and to Scottish or North Irish settlers.

Plate 25, Janetville Road, private dwelling Details

While rough coursed stone presents a rather picturesque scene, it is not as structurally stable as cut stone such as in the stone house built by McGill, a Northern Irishman, in 1865 ( Plate 25). This is a fine example of the stone mason’s art of well-cut finished stone with a sham gothic window in the centre gable, a square transom and returned eaves. The house has a solid ground hugging appearance derived from its simple lines and fine craftsmanship.

Plate 23, Highway 7, Reaboro, private dwelling Details

The earliest stone houses were built of rough coursed fieldstone as in Plates 23 and 24. The house in Plate 23 was built in the 1830s in Ops and has that early architectural feature of the transom over the door. This house was probably an early roadside inn.

Plate 24, Stone house, Eldon Township, private dwelling Details

The second example of rough coursed fieldstone is the Gunn house in Eldon Township, built circa 1850. Large boulders drawn straight from the fields were used as corner quoins.

Next to the need to erect cover, i.e. to build a house, the other major building concern of the settler was to erect barns and outbuildings. And the best of these buildings show that same fine craftsmanship and attention to structural detail that one finds in houses, as well as being suited to their functional purposes of providing storage space for crops and cover for domestic animals. There have been two types of barn adapted to use in Central Ontario. The earliest was the English barn, and later, with diversification into livestock, the Pennsylvania German.

Plate 27, English grain barns, Mariposa Township Details

The English barn belongs to the earliest period of settlement when the functions of barn and stable remained separate. The barn itself was used only for storage of fodder with room for a granary and rested either directly on the ground or was raised two or three feet by a stone sill. The barn was divided into two mows with a central threshing floor. On each long side of the barn there was a door to allow a strong breeze through the threshing floor so as to carry away the chaff when the wheat or oats were flailed (see Plate 27). Now only one door is used while the threshing floor serves as storage space for farm machinery during the winter. The English barn is easily identified by its simple rectangular design though there are some variations with what are known as saltbox roofs. Crosses, stars, colourful lightning rods, carved out dates and various animal weather vanes all served to fancy up even utilitarian buildings. Many of the English barns have survived down to the present but are difficult to date since many have been rebuilt on concrete foundations to accommodate a ground level stable.

In most cases log barns follow most clearly the English plan. Later frame barns of the English pattern are just large enough to require at least a feature or two from the Pennsylvania German style; such as the banked earth gangway (Plate 27).

In most cases log barns follow most clearly the English plan. Later frame barns of the English pattern are just large enough to require at least a feature or two from the Pennsylvania German style; such as the banked earth gangway (Plate 27).

Plate 26, English log barn, Carden Township Details

The first example we have, then, is a log barn from Carden Township which follows the above plan but with a few interesting innovations added by its builder (see Plate 26). The barn has the traditional two mows divided by a threshing floor. The log construction is square lap keyed and the internal division of the mows can be seen clearly on the face of the exterior wall. Interestingly, the stables have been built as adjuncts to the barn at each end. These stables have then had their floors dug out so as to permit a unique feeding system. Since the buildings appear to be all at one level, a great deal of carrying fodder would have had to be done. But, since the stable floors are dug out, the stable manger is actually underneath the barn. On the floor of the barn trap doors have been inserted that open directly into the mangers. So, all the farmer had to do was fork the hay out onto the threshing floor and from there directly into the mangers through the trapdoors in the sides of the mow above the threshing floor. The threshing doors of the barn are another unusual feature. They are hung on wooden posts that turn within a hole in the sill and above, in an overlapping bracket in the plate; therefore no iron hinges are necessary.

More typical of the English barns in the county are the small perpendicular barns seen in Plate 27. These barns were a common feature of the nineteenth century grain economy when wheat and oats were the predominant crops. These grain barns are particularly common in the commercial agricultural crescent of the county; i.e. Emily, Ops, Mariposa and Eldon.

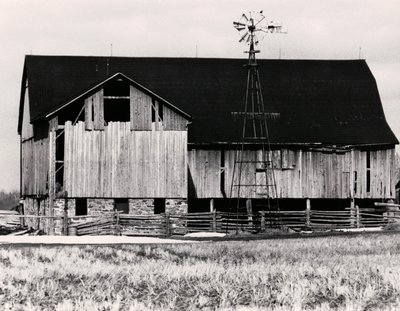

Plate 28, Pennsylvania Dutch barn, Mariposa Township Details

As the commercial agricultural economy changed from a one crop orientation to a more diversified production that included livestock, dairy products, mixed grains and such fodder crops as hay and corn, the design of barns changed also. To answer this need the larger gambrel roof frame barn, that incorporates a ground level stable built of stone, was built. These barns are directly descended from the large Pennsylvania German barns developed in the middle colonies of the United States. In the United States these barns generally feature a fore bay, i.e. an open space on the ground floor supported by wooden or stone pillars that faced south to give protection to the livestock. There are a few examples of such an arrangement in the county, as in Plate 28. But, in general, the practice soon disappeared in Ontario due to the harsh climate.

These barns still incorporated two doors on their long sides for a threshing floor and some were equipped with a system of pulleys and slings to move fodder; an indication of the increasing mechanization of late nineteenth Canadian agriculture. A few barns even had elongated gable ends so that the hay could be lifted by pulleys and slings right off the wagon when it was outside. There is a good example of this on County Highway 6 between Oakwood and Little Britain.

These barns still incorporated two doors on their long sides for a threshing floor and some were equipped with a system of pulleys and slings to move fodder; an indication of the increasing mechanization of late nineteenth Canadian agriculture. A few barns even had elongated gable ends so that the hay could be lifted by pulleys and slings right off the wagon when it was outside. There is a good example of this on County Highway 6 between Oakwood and Little Britain.

Plate 30, "McQuarrie" Barn, Built 1915, Eldon Township Details

The height of barn building in the county was reached at the turn of the century and culminated in the immense barns built as a result of the agricultural boom of World War I. A particularly fine example is the McQuarrie barn in Eldon Township (Plate 30). Here we have the ground floor stable, with immense stone walls and double hung windows, a huge barn on the second level with a gambrel roof, picturesque ventilators, and smaller, scattered windows and doors for further ventilation. This barn has a rather unusual feature in the large oak staircase as well as the usual vertical built-in ladders that accompanied the massive bents.

Plate 29, Lip Vault Frame Barn with Wooden Silo, Mariposa Township Details

The louvered windows in the roof are another interesting feature that appear on other local barns for picturesque and ventilative purposes; see especially Plate 29, a fine example of this as well as wooden corn silo with a multi-sided glass top.

The barn is a particularly instructive mode of vernacular building. Barns were built within the narrow demands of function and with the participation of the whole community in such events as barn raising bees. At best, the architecture showed only the hand of the master carpenter or builder. And yet, as folk architecture, they managed to combine an encomium of materials and plans to produce forms of simple and yet pleasing, and even sometimes impressive, appearance.

The barn is a particularly instructive mode of vernacular building. Barns were built within the narrow demands of function and with the participation of the whole community in such events as barn raising bees. At best, the architecture showed only the hand of the master carpenter or builder. And yet, as folk architecture, they managed to combine an encomium of materials and plans to produce forms of simple and yet pleasing, and even sometimes impressive, appearance.

The two concomitants to rural growth and prosperity, for communities as well, were transport and processing industries. Roads, canals and the railroads all played a decisive role in bringing the individual producer closer to the market place and the merchant to prospective customers. Individual industries, such as grist mills, lime kilns, grain elevators, breweries, cheese factories and creameries also played a decisive part in processing the raw products and thus introducing the farmer and laborer to a cash economy. The cash economy then encouraged the farmer to rationalize his business by building larger barns, draining fields and to introduce better crop and livestock varieties. Communications and processing industries each reinforced the other in developing Victoria County’s two main industries; a prosperous commercial agriculture in the south and a huge lumber export business in the north that was supplemented by a feeder economy based on hay and livestock for the shanties. By the end of the nineteenth century, transportation and processing had evolved to the point where small manufactories even existed as in Horn Bros. Woollen Mills and Sylvester’s Implement Works in Lindsay.

Plate 31, Pioneer lime kiln, Eldon Details

One of the earliest rural industries was the burning of lime for mortar in chinking and the laying of foundation (see Plate 31). This kiln lies in Eldon Township. It was a partial circle of stones built into a hill to a depth of 8 feet. The limestone was burned for two or three days and then broken up into powder to be mixed with clay and water from a local stream.

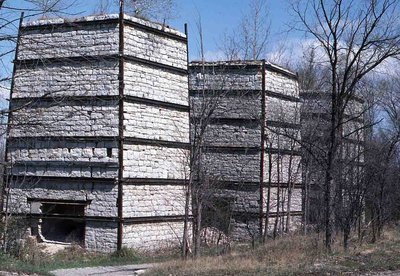

Plate 32, Lime Kilns, Coboconk Details

In 1889 commercial lime kilns were built at Coboconk to take advantage of the rich deposits of limestone in the area, as well as the cheap and abundant cordwood fuel. At one time, there was also a commercial lime kiln at Bobcaygeon, but it has been demolished. These furnaces (Plate 32) were kept burning for days to produce high quality lime that was shipped to Montreal and Toronto. With the advent of mass produced concrete, these wood burning furnaces were phased out of use.

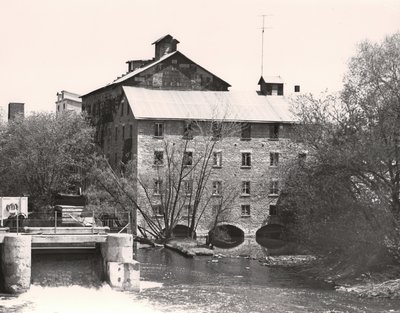

Plate 33, Purdy's Mill, Kent Street East, Lindsay Details

Of course, the earliest processing industry in a newly opened area was the local grist mill. Purdy’s Mill (Plate 33), built in fire resistant stone in 1869, is one of the finest examples of mill construction in the province. Reflecting its later date, its machinery was run by internal turbines, the intake being at the north side and the water being ejected out of chutes at the building’s base below the mill pond.

Plate 35, Lorneville Creamery Details

As the agricultural economy matured, other processing and storage industries began. In the towns there were grist mills, tanneries and woollen and carding mills. In the countryside small industries, such as cheese factories (Plate 34) and creameries, (Plate 35) sprang up when methods were developed to ship cheese and separate cream from milk. Many of these small industries were cooperatives organized by the farmers themselves. They also involved themselves in such enterprises as building grain elevators, organizing country fairs and working together politically in the Patrons of Industry. These local processing industries often represented the only source of cash for the struggling farmer and, as agents of prosperity, they played a vital role in developing Victoria’s agriculture.

Plate 34, Cheese factory, Bobcaygeon, Verulam Township Details

Plate 36, Sawmill, Kinmount Details

Of the lumbering economy, little physical evidence remains. The only surviving frame mills are the water powered mill built at Kinmount in 1942 (see Plate 36), with its nineteenth century machinery from a Haliburton mill, and the steam powered mill at Kirkfield. Major lumber mills once existed at Omemee, Lindsay, Coboconk and Burnt River. But lumbering was most crucial to local prosperity in Fenelon Falls and Bobcaygeon; both of which suffered a decline when the mills shut down in the mid-1880s. The one pervasive physical effect of lumbering was to change the landscape to such a degree that the white pine has virtually disappeared.

Plate 38, Stage Coach Inn, 1846, Emily Township Details

The other side of Victoria’s economic development was the opening up of transport routes. First there were rough corduroy roads that cut across the concessions as stage coach lines on the commercial routes between Lindsay and Port Perry, Port Hope and Bobcaygeon, etc. The only surviving evidence of these routes is a few roadside taverns that have long been converted to private residences. Inns, once ubiquitous as gas stations, are extremely rare. Fortunately we have two fine stone examples. Plate 38 was built in 1846 on the stagecoach line between Port Hope and Bobcaygeon.

Plate 39, Stone Inn, Highway 7, Ops Township Details

Our second roadside inn (Plate 39) was built on the road between Lindsay and Oakwood that eventually led to Port Perry; a terminus for Victoria’s lumber and grain in the 1830s, 40s and 50s before the advent of the railroad.

Plate 41, Lift Locks, Kirkfield Details

The second transport route to be opened up consisted of selected points in the Trent navigational system, such as timber slides at Bobcaygeon, Fenelon Falls, Rosedale and Lindsay, to facilitate the rafting of timber down to mills or, more importantly, to imperial markets from Trenton to Quebec City to Great Britain. At the close of the nineteenth century, the completion of the Trent Canal system was begun in earnest. At the time, the canal promised to bring prosperity by funneling the grain trade of the west through Central Ontario. But neither the canal nor the railroad could ever seriously compete with the Great Lake shippers. Now the canal serves as one of the most picturesque routes for pleasure boating and one of the most spectacular attractions is the Kirkfield Lift Locks built in 1906-07 (Plate 41). The two locks ride on huge hydraulic pistons that move up and down by the transference of hydraulic fluid from one piston to the other. They move a distance of forty-eight and a half feet and, with the Peterborough Lift Locks, eliminate a series of expensive locks by one huge drop.

While the canals played a decisive role in accelerating the growth of such towns as Bobcaygeon and Fenelon Falls by facilitating the exploitation of Victoria’s forest resources, the real economic take off point for agriculture in South Victoria and small-scale industry in Lindsay was begun by the penetration of the railroad; first the Lindsay and Port Hope Railway in 1857 and later the Toronto and Nipissing, the Whitby, Port Perry and Lindsay Railway and the Victoria Railway.

While the canals played a decisive role in accelerating the growth of such towns as Bobcaygeon and Fenelon Falls by facilitating the exploitation of Victoria’s forest resources, the real economic take off point for agriculture in South Victoria and small-scale industry in Lindsay was begun by the penetration of the railroad; first the Lindsay and Port Hope Railway in 1857 and later the Toronto and Nipissing, the Whitby, Port Perry and Lindsay Railway and the Victoria Railway.

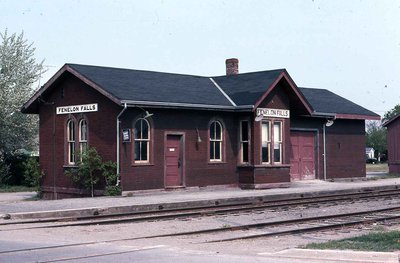

Plate 42, Train Station, Fenelon Falls Details

Many of the small frame stations have survived in the countryside, though not in Lindsay. But those that have survived are usually in a dilapidated state. One of the best examples is the CNR station in Fenelon Falls (Plate 42). Note the projecting telegrapher’s bay which gave the agent a clear view of the tracks.

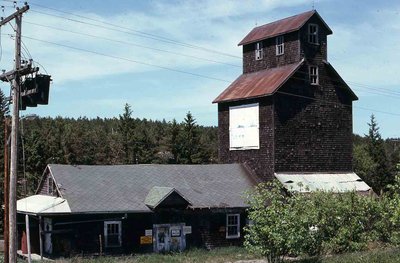

Plate 43, Grain elevator, Pontypool Details

The commercial function of the railroad is nowhere better illustrated than in the miniature railway complex at Pontypool with its station, freight sheds, flag station, cattle chute and grain elevator (Plate 43). Despite the advantages of roads and canals, it was the railroad that decisively changed the tempo and speed of Victoria’s development.

Rural architecture, the architecture of industries and transportation present a rich and varied canvas. But the architecture of materials and the workplace were just one part of the nineteenth century life in Victoria County.

Rural architecture, the architecture of industries and transportation present a rich and varied canvas. But the architecture of materials and the workplace were just one part of the nineteenth century life in Victoria County.