Pro History Project: History by Design

III. Estates

Panels

Pro History ProjectOral HistoriesFrom The Heartland: Ninteenth Century Buildings of Victoria CountyAcknowledgementsIntroductionThe Heartland in PerspectiveI. Rural Life, Industries and TransportationII. CommunitiesIII. EstatesIV. Gathering PlacesConclusionBibliographyMissing Slides and PhotographsLinks

Pro History Colour SlidesOral HistoriesPro History Black & WhiteAt the apex of the social scale, measured in proportion to one’s wealth, religious or cultural attainments, stood those families who deliberately advertised their prominence through such ostentatious dwellings as the Dunsford’s ‘Beehive’, the Mossom Boyd house in Bobcaygeon and the Mackenzie estate in Kirkfield.

At the earliest opening of what were then the back townships of Fenelon Falls and Verulam in the Newcastle District, a remarkable collection of English gentlemanly society gathered. This society consisted of such well known personalities as John and Anne Langton, known through their published letters, half pay officers, such as Admiral Van Sittart on the north shore of Balsam Lake in Bexley, professionals, such as the Reverend Dunsford, and merchants such as Wallis, Need and Boyd; men who began the lumber and grist mills and canal works at Fenelon Falls and Bobcaygeon.

This backwoods society of gentleman farmers and rising mercantile capitalists was a remarkable transplantation of English cultural and educational attainments to a rugged, sparsely settled region far from the goods and diversions offered by an urban or an agriculturally mature area. This society flowered in a brief effervescence of sailing regattas, hunting parties, university club, sketching, polished letters, emigrant guides and even novel writing. This gentleman’s backwoods society stretched from the Traill’s at Lakefield to the half pay officers settled in or near Beaverton in Ontario County. On the west side of Lake Simcoe stood the mansion of Captain E. Steele in Simcoe County and so on across the province.

In the wake of the post Napoleonic depression and disbandment of the huge military services, scores of lower gentry, half pay officers, and rising mercantile families, such as the Langtons, left Great Britain for fairer prospects in the new world. After a brief period of reproducing the social forms of the past, these, often propertied, immigrants were assimilated into Canadian society; often in its mercantile branches since they brought capital with them. This soon established them as part or even initiators of the local mercantile elite of mill owners, wholesale buyers of primary products, or as leading professionals in the fields of medicine, law and government services.

This backwoods society, however, soon disappeared as it proved unable to transplant the social and political forms of English gentry life to a raw land where labour and initiative were at a premium; where the business of developing the countryside could not wait for the social subordination involved in these families’ self-assumed prerogative to rule (often strengthened by being appointed a Justice of the Peace to the Quarter Sessions) before there was anything or any great numbers of people to rule over.

At the earliest opening of what were then the back townships of Fenelon Falls and Verulam in the Newcastle District, a remarkable collection of English gentlemanly society gathered. This society consisted of such well known personalities as John and Anne Langton, known through their published letters, half pay officers, such as Admiral Van Sittart on the north shore of Balsam Lake in Bexley, professionals, such as the Reverend Dunsford, and merchants such as Wallis, Need and Boyd; men who began the lumber and grist mills and canal works at Fenelon Falls and Bobcaygeon.

This backwoods society of gentleman farmers and rising mercantile capitalists was a remarkable transplantation of English cultural and educational attainments to a rugged, sparsely settled region far from the goods and diversions offered by an urban or an agriculturally mature area. This society flowered in a brief effervescence of sailing regattas, hunting parties, university club, sketching, polished letters, emigrant guides and even novel writing. This gentleman’s backwoods society stretched from the Traill’s at Lakefield to the half pay officers settled in or near Beaverton in Ontario County. On the west side of Lake Simcoe stood the mansion of Captain E. Steele in Simcoe County and so on across the province.

In the wake of the post Napoleonic depression and disbandment of the huge military services, scores of lower gentry, half pay officers, and rising mercantile families, such as the Langtons, left Great Britain for fairer prospects in the new world. After a brief period of reproducing the social forms of the past, these, often propertied, immigrants were assimilated into Canadian society; often in its mercantile branches since they brought capital with them. This soon established them as part or even initiators of the local mercantile elite of mill owners, wholesale buyers of primary products, or as leading professionals in the fields of medicine, law and government services.

This backwoods society, however, soon disappeared as it proved unable to transplant the social and political forms of English gentry life to a raw land where labour and initiative were at a premium; where the business of developing the countryside could not wait for the social subordination involved in these families’ self-assumed prerogative to rule (often strengthened by being appointed a Justice of the Peace to the Quarter Sessions) before there was anything or any great numbers of people to rule over.

Plate 93, The Dunsford House Details

Such an elaborate picturesque exercise in social ostentation as the Dunsford’s log mansion (Plate 93), known as the ‘Beehive’ and built in 1839, effectively demonstrates the imagination and tastes of a transplanted culture fused with the demands of the Canadian environment. This has been imaginatively done, however, in making a virtue out of the log medium. But, as Anne Langton slyly remarked, “Hitherto I fancy we have more English elegancies about us than most of our neighbours, but the Dunsfords, I expect, will quite eclipse us, for they, it is said, are bringing a carriage out with them. I hope they do not forget to bring a good road too”. (Clarke and Irwin, p. 59)

Canadian society has changed a great deal from when fortunes could be made from local natural resource exploitation, as in the case of the Boyds’ lumber business, William Cottingham’s mills at Omemee, the Hogg and Lytle grain business in Mariposa or from railway building and speculation, as in the spectacular example of Sir William Mackenzie and the Canadian Northern or as in the more local example of George Laidlaw, a railway promoter for the Toronto and Nipissing, who eventually resided at the ‘Barracks’ on the former property of Admiral Van Sittart on the north shore of Balsam Lake.

Plate 105, Sir William Mackenzie summer cottage, Balsam Lake, Bexley Township Details

The houses they have built have either disappeared, been restored as local museums, or have sadly deteriorated to be fragmented into apartment dwellings. One has only to contemplate the once rambling but impressive summer cottage (Plate 105) where the Mackenzies entertained Prime Minister Borden to appreciate the decline and eventual disappearance of an almost purely local provincial elite of mercantile capitalist families.

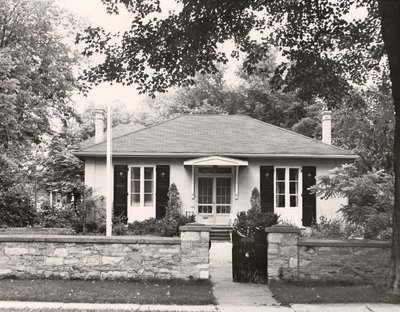

Plate 94, Wallis House, Oak Street, Fenelon Falls Details

One of the few remaining ‘cottages’ of this period is the Wallis home in Fenelon Falls (Plate 94). Originally a frame building constructed in 1837, it displays one of those key characteristics of early picturesque building in Canada and this is, the French doors (see the Ontario Cottage in Plate 45 for a similar example). Now French doors provide a clue to the ‘picturesque’ perception of how buildings should be built by concentrating on the relationship of nature to men’s dwellings. By the use of irregular outlines, verandahs with climbing treillage, French doors and lowness of profile, nature and man were inextricably linked by a romantic perception of man’s place in an orderly and yet ‘natural’ environment. To turn Northrup Frye’s aphorism on its head, the bush was the garden to the early Victorian who was guided in his perceptions by a concern for the picturesque.

Plate 45, Ontario Cottage, Bond Street, Lindsay, private dwelling Details

No such aesthetic considerations bothered those later mercantile families who prospered to rise to the top of provincial society. They deliberately set out to prove their new found worth through large buildings with a landscape subordinate to man’s works. The environment was as much rationalized as made picturesque by extensive lawns, flower beds and, always, a massive fence to reinforce the message of social exclusiveness.

The Boyd and Mackenzie estates follow this plan down to the last detail, as do other smaller houses that imitate such deliberate effects within their means (such as the low wall around the Ontario Cottage in Plate 45).

The Boyd and Mackenzie estates follow this plan down to the last detail, as do other smaller houses that imitate such deliberate effects within their means (such as the low wall around the Ontario Cottage in Plate 45).

Plate 96, Boyd Estate, Bobcaygeon Details

Boyd Estate, Bobcaygeon Details

Plate 101, Mackenzie House, Nelson Street, Kirkfield Details

And across the road from William Mackenzie’s house was his brother, A.C. Mackenzie, in a buff brick mansion surrounded by the customary wall. Each also reflected certain peculiarities of their ethnic or personal experiences. In the Boyd’s case, one finds the wall surrounding the estate to be of Scottish craftsmanship, built by Scots masons specially imported for the task, and, in Kirkfield, there is Lady Mackenzie’s huge water tower (Plate 101), built for watering her flowers, and gargoyle lawn seats brought back from a trip to Italy.

Plate 99, Mackenzie House, Nelson Street, Kirkfield Details

The Boyd and Mackenzie houses (Plates 96 and 99) are both examples of upper class colonial building. Each is built over an older house that has been remodeled, embellished and enlarged to appear as late Victorian mansions. As late Victorian houses, they suffer from a lack of definitive style. They have height, irregularity of roof line, sumptuous interiors, and yet lack any solid grounding in any particular style that would truly set them apart aesthetically from the smaller but architecturally similar buildings of the local mercantile and professional elite. But then, this similarity of taste is a good indicator of the continuity of the mercantile class distinguished only by greater wealth and, therefore, the availability of an architect’s services. What these houses really have that distinguishes them from similar architecture is size. And this, of course, is not architecture but an expression of social values.

Plate 102, Boyd Barn, Highway 36, Bobcaygeon Details

Both estates are more than the main house. Each was supplemented by outbuildings, such as dairy barns (plate 102)

Plate 95, Boyd Lumber Office, Canal Street East, Bobcaygeon Details

and related enterprises such as the Boyd building, constructed in 1891 and housing the Boyd Lumber office (plate 95) the private tutor’s schoolroom, W.T.C. Boyd’s office, and the Trent Valley Navigation office

Plate 103, "Annex" to "Kirkfield Inn" Details

and such others as the Annex (plate 103) to the incredibly expensive Kirkfield Inn which burnt down after a very few years of service leaving only the Annex and stables.

Plate 98, Case Manor, Boyd Estate, Bobcaygeon Details

Each estate was also flanked by relatives and dependents’ houses. Just to the east of the Mossom Boyd house was his son’s, W.T.C. Boyd, a late nineteenth century brick mansion embellished with oriental treillage (Plate 98).

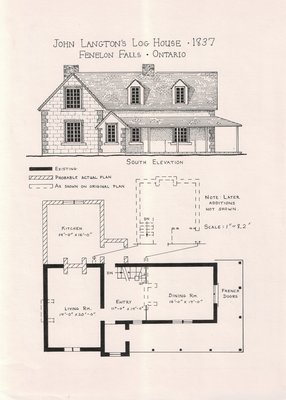

John Langton's Log House, 1837, Fenelon Falls Details

Langton’s “Blythe House” has not been so favourably treated by time. Though demolished, J. Remple’s analysis of how the house was built, and for certain aesthetic purposes (in Building with Wood), is a useful commentary on early Victorian tastes such as the Langton’s concern to disguise the wooden wall to look like stone. Blythe House, with its attempt to disguise its natural materials, appears to our eyes a peculiar combination of smallness of scale and artificial refinement. But, to early Victorian sensibilities, this artificial effect was pleasing precisely because of such romantic literary associations as irregularity, variety of outline and the idea of the gentlemanly ‘cottage’.