We Are All Treaty People: Indigenous History in Kawartha Lakes

Treaties of the Kawartha Lakes

Panels

What is a Treaty?Treaties of the Kawartha LakesTreaty 20: Rice Lake Land SurrenderIndigenous Peoples in the Kawartha Lakes Treaty RegionsManita: An Indian LegendManoomin: The Good SeedThe Indian Act, 1876Residential "Schools" or Industrial "Schools"Truth and Reconciliation

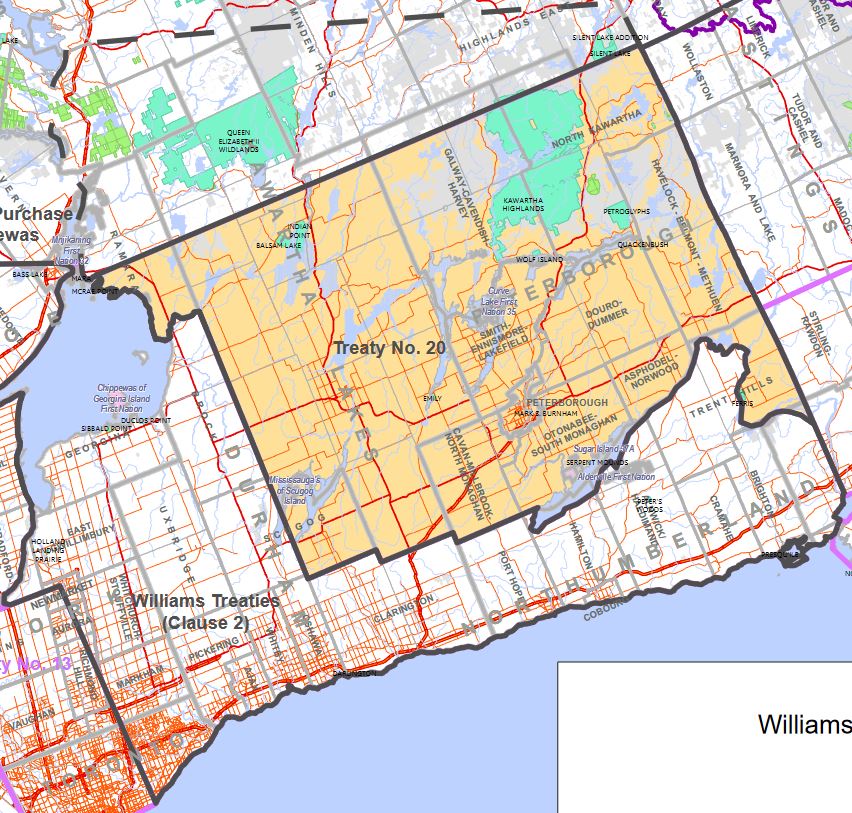

Williams Treaties and Pre-Confederation Treaties of Kawartha Lakes Details

There are two active treaties in place which state the living agreements currently in place upholding and protecting Indigenous rights to land, resources, water, health care, education, and much more in the area of Kawartha Lakes. First Nations representatives signed the treaties to allot some lands and sharing of resources from these lands (to the depth of a plow) to ensure their People were looked after for many generations to come. First Nations believed they were merely giving the new settlers the right to use some of their lands for farming. First Nations Peoples did not give up all title to their land, nor could they even comprehend the concept of extinguishment of all title and all rights to their lands forever.

The first of these active treaties is Treaty 20, sometimes called the Rice Lake Purchase or the Rice Lake Land Surrender. Numerous Peoples of the Michi Saagiig Nation were signatories to this treaty and 16 other treaties prior to this one signed in 1818.

The second of these active treaties is the Williams Treaties, established in 1923 with one signing for the Chippewas of Beausoleil First Nation, Georgina Island First Nation, and Rama First Nation and one signing for the Michi Saagiig Nation or Missisaugas of Alderville First Nation, Curve Lake First Nation, Hiawatha First Nation, and Scugog Island First Nation. No negotiations preceded the signing of the Williams Treaties in 1923. Instead, government officials dictated the terms that Canada and Ontario had decided earlier that year to the First Nations signatories. The reason for the governments’ haste may have had to do with the fact that Ontario was already using most of the territory in question, and therefore, officials were highly motivated to extinguish all remaining title to it. Historian Peggy J. Blair adds that First Nations peoples may have been ready to take their grievances to the League of Nations and to British officials in London, England in that same year, perhaps prompting the federal government to move quickly with the treaties.

By signing the treaties, the Crown received three tracts of land: the first lay between the Etobicoke and Trent Rivers and was framed by Lake Ontario’s northern shore, the second expanded north from the first to Lake Simcoe. Together, these tracts made up roughly 6,475 square kilometres. The third tract of land measured 45,584 square kilometres and lay between the Ottawa River and Lake Huron. In exchange, the Mississauga and Chippewa peoples received a one-time payment of $25 for each band member. The Mississauga also received $233,425, while the Chippewa received $233,375 (both were one-time payments). This money made up a fraction of their land’s estimated value.

When compared to the Upper Canada land surrenders and Numbered Treaties, the Williams Treaties provided less favourable terms for the First Nations signatories. The Chippewa and Mississauga peoples, who had no legal representation at the treaty talks, received modest lump sum payments for large sections of land instead of annuity payments distributed in perpetuity. The Williams Treaties also surrendered hunting and fishing rights to off-reserve lands —a significant departure from what had become common practice in the Robinson Treaties and Numbered Treaties.

An apology for the negative impacts of the 1923 Williams Treaties on the Williams Treaties First Nations was made by the Honourable Carolyn Bennett, Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations, on behalf of the Government of Canada on November 17, 2018 in Rama, Ontario.

Information provided by The Land Between and The Canadian Encyclopedia.

The first of these active treaties is Treaty 20, sometimes called the Rice Lake Purchase or the Rice Lake Land Surrender. Numerous Peoples of the Michi Saagiig Nation were signatories to this treaty and 16 other treaties prior to this one signed in 1818.

The second of these active treaties is the Williams Treaties, established in 1923 with one signing for the Chippewas of Beausoleil First Nation, Georgina Island First Nation, and Rama First Nation and one signing for the Michi Saagiig Nation or Missisaugas of Alderville First Nation, Curve Lake First Nation, Hiawatha First Nation, and Scugog Island First Nation. No negotiations preceded the signing of the Williams Treaties in 1923. Instead, government officials dictated the terms that Canada and Ontario had decided earlier that year to the First Nations signatories. The reason for the governments’ haste may have had to do with the fact that Ontario was already using most of the territory in question, and therefore, officials were highly motivated to extinguish all remaining title to it. Historian Peggy J. Blair adds that First Nations peoples may have been ready to take their grievances to the League of Nations and to British officials in London, England in that same year, perhaps prompting the federal government to move quickly with the treaties.

By signing the treaties, the Crown received three tracts of land: the first lay between the Etobicoke and Trent Rivers and was framed by Lake Ontario’s northern shore, the second expanded north from the first to Lake Simcoe. Together, these tracts made up roughly 6,475 square kilometres. The third tract of land measured 45,584 square kilometres and lay between the Ottawa River and Lake Huron. In exchange, the Mississauga and Chippewa peoples received a one-time payment of $25 for each band member. The Mississauga also received $233,425, while the Chippewa received $233,375 (both were one-time payments). This money made up a fraction of their land’s estimated value.

When compared to the Upper Canada land surrenders and Numbered Treaties, the Williams Treaties provided less favourable terms for the First Nations signatories. The Chippewa and Mississauga peoples, who had no legal representation at the treaty talks, received modest lump sum payments for large sections of land instead of annuity payments distributed in perpetuity. The Williams Treaties also surrendered hunting and fishing rights to off-reserve lands —a significant departure from what had become common practice in the Robinson Treaties and Numbered Treaties.

An apology for the negative impacts of the 1923 Williams Treaties on the Williams Treaties First Nations was made by the Honourable Carolyn Bennett, Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations, on behalf of the Government of Canada on November 17, 2018 in Rama, Ontario.

Information provided by The Land Between and The Canadian Encyclopedia.